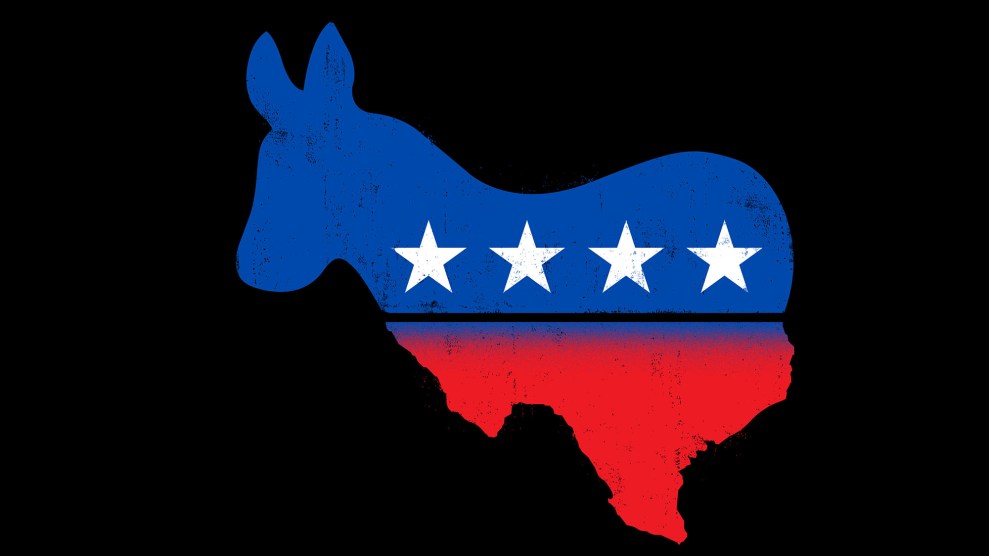

Beto O'Rourke announces the end of his campaign.Jack Kurtz/Zuma

On Friday afternoon, former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke announced he was dropping out of the Democratic presidential primary, just a few hours before he was scheduled to speak at the Iowa Democratic party conclave formerly known as the Jefferson-Jackson Dinner—the event that helped propel Barack Obama’s candidacy 12 years ago. Instead, the man who’d once drawn serious comparisons to the 44th president (and been egged on by former Obama staffers) would be heading home to El Paso, personal and professional future TBD.

O’Rourke’s campaign ended far less dramatically than it started—with the candidate posed, Reagan-like, on the cover of Vanity Fair—but if we’re being honest, almost every campaign does. It is the nature of presidential politics to take smart candidates who have succeeded at virtually everything else and make them look like idiots. (Also, there are lots of idiot candidates who continue to look like idiots, and sometimes idiot candidates who are unfortunately made to look smart—tag yourself!)

But the end of the road this time was all the more striking given what preceded it. O’Rourke’s 2018 campaign against Texas Sen. Ted Cruz was one of the more remarkable losing campaigns in a generation, a relentless 20-month push that defied conventional norms about how to campaign. His presidential campaign was… well, it wasn’t like that.

The O’Rourke who entered the race as an almost-frontrunner was a different candidate from the one who finished it, and—though there was a lot to say about the first version—the second one was more compelling. It wasn’t until O’Rourke’s polling flagged and he dropped out of the top tier that he seemed to find his purpose. Then, his campaign changed for good after a white-supremacist gunman massacred Hispanic shoppers at a Walmart in his hometown of El Paso, O’Rourke became the candidate most singularly focused on gun violence. As Benjamin Wallace-Wells put it in the New Yorker this summer, he became “more marginal but more interesting: a protest candidate, an antiwar politician, for a different kind of war.”

Just days after the shooting, a reporter asked him if Trump could do anything to make things better. O’Rourke unloaded: “He’s been calling Mexican immigrants rapists and criminals—members of the press, what the fuck?” he said, asking reporters to “connect the dots” for themselves. As media criticism goes, it wasn’t half-bad.

After staking out newly aggressive policy positions on gun control, he demanded his rivals follow his lead. Most notably, he called for a mandatory buyback of assault rifles—a realization of decades of conservative propaganda about liberals coming for your guns, sure, but also a proposal that honestly grapples with the stockpile that would be left if all legislation did was halt new sales. “Hell yes, we’re going to take your AR-15,” he said. No one else was so bold—Pete Buttigieg called him crazy, and O’Rourke, as my colleague Kara Voght pointed out, was staking out a position considerably more aggressive than what gun control advocates in the House were actually calling for. But it was something new.

If 2018 Beto was a mirror who reflected voters’ ideas about who he was, O’Rourke in 2019 was the inverse, trying to get the electorate to mirror his moves. It was a bet about where the progressive movement was headed, as well as an effort to lure them there. In some cases his instincts were misguided. O’Rourke’s desire to just let loose and channel the progressive id, perhaps, led him to call in September for churches who don’t recognize same-sex marriage to lose tax benefits—a position that conservatives were quick to weaponize and other Democrats avoided like a subway puddle. For all the right’s railings against the slippery slope to socialism, it might be these kinds of attacks on cultural shibboleths like gods and guns that conservatives fear most.

O’Rourke campaigned more than almost anyone else in the field—partly because he had no other job, sure, but also because the idea with O’Rourke has always been to be everywhere. His post-shooting itinerary brought him to Skid Row, to Black Wall Street, to Ciudad Juarez, and, just as he had in his Senate campaign, developed a reputation for barnstorming, standing on objects, holding forth and taking all questions. But the difference between doing that in Texas and doing that in Iowa is stark. People in Odessa might feel like they’ve been ignored by Democratic politicians all their lives. People in Cedar Rapids do not.

In the end there are many explanations for why O’Rourke failed. But the simplest one is universal—copy and paste it for the next time someone significant drops out, and for the time after that. He was not running against the most hated man in the Senate anymore. Instead, he was running against Barack Obama’s (or, please, just “Barack’s”) vice president, the 2016 primary runner-up, and a senator who has captivated so many progressives for so long that she has her own unofficial wing of the party named for her. As O’Rourke wished his supporters well and wrapped up the final rally of this campaign, another one was still going strong behind him—for supporters of a man who not long ago passed Beto in the polls, Andrew Yang. Stay in the game long enough, and eventually the math comes for us all.