President Donald Trump shakes hands with Chief Justice John Roberts at his first address to a joint session of Congress in 2017.Jim Lo Scalzo/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

In 1997, Duane Buck, a 34-year-old African American man, was convicted of double murder in Texas. At the trial, a court-appointed psychologist called as a witness by Buck’s lawyer testified that Buck was more likely to commit future violent crimes because he was black. “Race. Black: Increased probability,” the expert report said. Influenced by this evidence, a jury sentenced Buck to death.

Buck appealed to the Supreme Court, alleging that his Sixth Amendment right to effective counsel had been violated. In 2017, the Supreme Court reversed the death penalty conviction in a 6-2 decision, with Chief Justice John Roberts writing for the majority.

“There is a reasonable probability that Buck was sentenced to death in part because of his race,” Roberts wrote. “This is a disturbing departure from the basic premise that our criminal law punishes people for what they do, not who they are. That it concerned race amplifies the problem. Relying on race to impose a criminal sanction ‘poisons public confidence’ in the judicial process.”

With the Supreme Court set to rule in the coming days on the legality of the Trump administration’s addition of a citizenship question to the 2020 census, all eyes are on Roberts, now the court’s ostensible swing justice after the retirement of Anthony Kennedy. Many are wondering which Roberts we’ll see—the pragmatic justice who saved the Affordable Care Act in 2012 and has occasionally, as in the Buck case, sought to redress egregious instances of racial discrimination? Or the hard-edged conservative who wrote the majority opinion gutting the Voting Rights Act in 2013 and has spent much of his career trying to roll back civil rights for racial and ethnic minorities? His ruling in the census case will determine Roberts’ legacy—and that of the court he presides over—for many years to come.

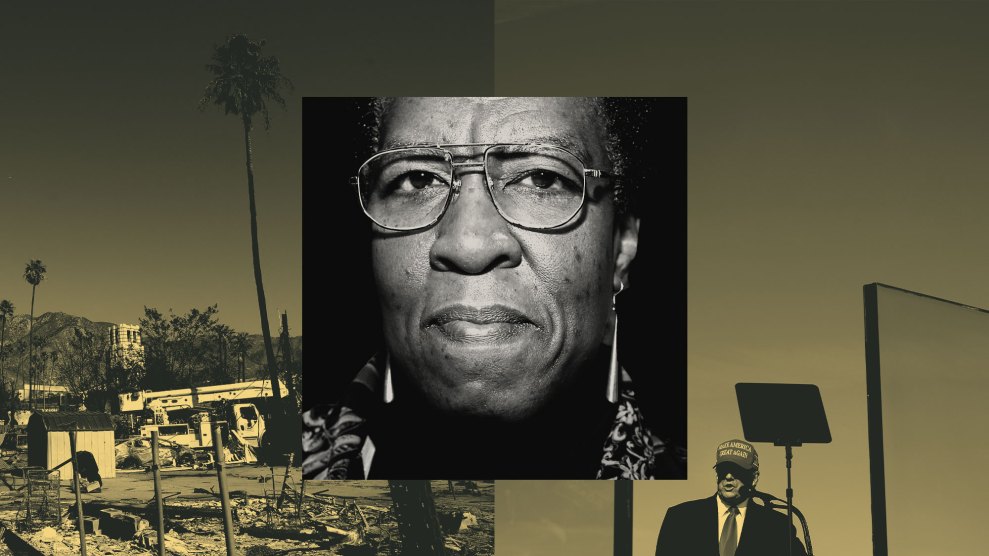

At stake is whether Roberts will allow the Trump administration to rig American politics for the next decade by corrupting the census, and turn the Supreme Court—which he has often said should stay above partisan politics—into an unmistakable ally of the Republican Party and white power. If the court upholds the administration’s addition of the question, experts say, it would reduce census participation by immigrants afraid of being targeted by the government and diminish the political power and economic resources of parts of the country where many immigrants live. Roberts’ views on race tell us a great deal about how he’ll rule on the case. “He believes racial discrimination exists but he has a quite narrow view of what constitutes legally actionable discrimination,” says Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

The census case is the ultimate test for Roberts, especially in light of last month’s bombshell revelations that the Republican Party’s longtime gerrymandering mastermind, Thomas Hofeller, was behind the administration’s push for the citizenship question. Hofeller, newly discovered documents revealed, said the question “would clearly be a disadvantage to the Democrats” and “advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites.” Hofeller, who ghostwrote part of the Justice Department’s letter formally requesting the addition of the question, told the administration to claim that it would help enforce the Voting Rights Act, when Hofeller’s own research concluded that it would harm the minority groups that the VRA was designed to protect.

The Hofeller evidence showed unmistakably that the point of the citizenship question was to transfer political power to white Republicans and diminish the clout of minority voters. That gives Ifill some hope that “when you now have the invocation of race, that might be right in the wheelhouse that Roberts finds problematic, where he realizes a line has been crossed.”

The ACLU filed a last-minute brief last week asking the court to send the case back to a lower court if it’s not prepared to reach a decision striking down the question. “The new evidence strongly suggests that [the Department of] Commerce’s real rationale was the diametric opposite of its stated reason: not to protect minority voting rights through better enforcement of the VRA, but to facilitate a partisan advantage in redistricting and to dilute the electoral influence of voters of color,” the filing says. “This new evidence thus underscores the pretextual basis for Commerce’s decision and suggests an unconstitutional, racially discriminatory motive.”

Yet Roberts has rarely acted as the conscience of the court or as an ally to those facing discrimination, especially in closely contested cases. Of the 800 cases he heard as chief justice between 2005 and 2017, he sided with the liberal justices in 5-4 cases only five times. His vote to uphold the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate has given Roberts a reputation for independence that is more myth than fact.

Roberts began his legal career during the conservative counter-revolution of the 1980s. After clerking for Justice William Rehnquist, who was known as the Lone Ranger on the court for his extreme right-wing views, Roberts joined the Reagan administration as a special assistant to Attorney General William French Smith. At the time, the conservative movement considered the remedies for historic discrimination—such as busing, affirmative action, and political districts drawn to elect minority candidates—as harmful as the original sin of discrimination. Roberts eagerly embraced this color-blind ideology and became the Reagan Justice Department‘s point person for weakening the Voting Rights Act. He wrote in one memo to his bosses that violations of the law “should not be made too easy to prove, since they provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable by federal courts into state and local processes.”

Thirty years later, Roberts finished what he started by gutting the core of the VRA, ruling that states with the longest histories of discrimination no longer needed to approve their voting changes with the federal government. “Things have changed dramatically” in the South, he wrote in Shelby County v. Holder, overlooking a lengthy record of historic and modern-day voting discrimination, not to mention the overwhelming vote by Congress to reauthorize the VRA in 2006. His decision unleashed an entirely predictable wave of new voter suppression efforts in states like Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas. Roberts has consistently endorsed Republican-backed laws that diminish voting rights for people of color, such as voter ID laws in Indiana, voter purging in Ohio, and racial gerrymandering in Texas.

A decision upholding the citizenship question “would be as monumental as the Shelby decision,” Ifill says. “It would demonstrate the court’s willingness to make flights of fancy over facts, and to make leaps and bounds to reach conclusions unsupported by any clear-eyed view of the evidence.”

Even before the Hofeller revelations, a wealth of evidence in the case undercut the Trump administration’s position. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who oversees the Census Bureau, claimed that the push for the citizenship question was “initiated” by the Justice Department for “more effective enforcement” of the Voting Rights Act, but memo after memo released during a federal trial showed that Ross himself had aggressively lobbied the department to request the question, after consulting with anti-immigration hard-liners like Steve Bannon, Kris Kobach, and Jeff Sessions. Ross had “no apparent interest in promoting more robust enforcement of the VRA,” federal district court Judge Jesse Furman wrote in January when he struck down the question in a blistering opinion, finding that Ross “alternately ignored, cherry-picked, or badly misconstrued the evidence in the record before him.” Two other federal courts reached the same conclusion.

Yet at oral arguments, Roberts and the other conservatives justices seemed broadly sympathetic to the administration’s argument. Roberts called the collection of citizenship data “the critical element” for the enforcement of voting rights cases. “Do you think it wouldn’t help voting rights enforcement?” he asked Barbara Underwood, the former New York attorney general, about the citizenship question. The fact that the Trump administration hadn’t filed a single lawsuit to enforce the Voting Rights Act—or that the conservatives on the court had gutted the law six years earlier—never came up.

“There’s a world in which, despite all of the smoking-gun evidence about the weaponization of the census for partisan and racial motives, the court and Justice Roberts just woefully ignore this and say it wasn’t part of the record and make this seem like a technical, arcane issue, which erases everything we know about why this question was added,” says Vanita Gupta, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights and the former assistant attorney general for civil rights in the Obama administration.

Indeed, for a telling comparison, just look at Roberts’s decision last year upholding the administration’s travel ban, which he said was not a Muslim ban even though President Donald Trump had called it exactly that.

If Roberts were to uphold the citizenship question, it would make clear that he values the preservation of white political power more than the court’s reputation as a fair and nonpartisan actor. More and more, the Roberts court would resemble the redemption court of the late 1800s and early 1900s, which solidified Jim Crow by refusing to enforce the civil rights laws passed during Reconstruction.

“When there’s a rigging of structural democracy and the Supreme Court has played such a significant role in sanctioning it, this is where the legitimacy of the court hangs in the balance,” Gupta says. “If they rule to keep the question on the census in the face of overwhelmingly evidence of bad motive, I don’t think the court will be able to recover from that.”