Jorge Sanjuan pulled back a chain-link fence, and Cindy Quezada squeezed through the gap. They stepped over two rotting mattresses and an old tire and peered into a backyard. The neighbors eyed them suspiciously. “You guys with ICE?” one teenager asked.

Quezada laughed and shook her head. It was a sunny January afternoon, and she and Sanjuan had spent the past three hours crisscrossing the alleys of a Fresno, California, neighborhood with small one-story bungalows and Mexican restaurants, looking for sheds, garages, and trailers serving as makeshift homes. They weren’t out to harass the immigrants living there; they were there to count them.

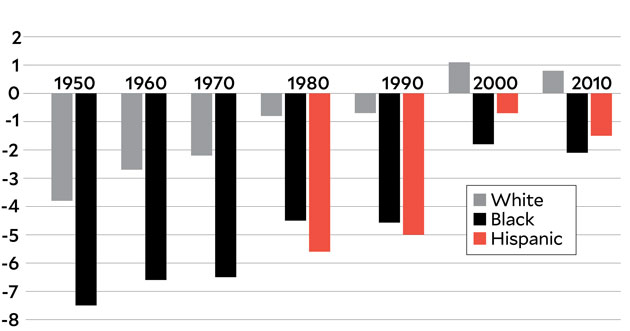

Quezada and Sanjuan were working with the Central Valley Immigrant Integration Collaborative, a network of organizations embarking on a pilot program to identify “low-visibility housing” in Fresno in preparation for the 2020 census. The Constitution requires the executive branch to tally “the whole number of persons in each state.” But every 10 years, the census counts some people more than once—such as wealthy Americans who own multiple homes—and others not at all, particularly those who are poorer, move often, or fear the government. The 2010 census, the most accurate to date, overcounted white residents by nearly 1 percent while failing to count 1.5 million people of color, including 1.5 percent of Hispanics, 2.1 percent of blacks, and 4.9 percent of Native Americans on reservations, the Census Bureau later concluded. Mexican immigrants were especially undercounted because the bureau didn’t know where they lived or because multiple families lived in one household.

That’s why Quezada and Sanjuan were in Fresno, where 70 percent of residents are people of color, 20 percent are immigrants, and one-third live in poverty, making it one of the hardest places in the country to count. Only 73 percent of residents in the east Fresno neighborhood they were canvassing mailed back their census forms in 2010—if they ever received them in the first place.

Cindy Quezada and Jorge Sanjuan canvass a neighborhood in Fresno, California, in January, looking for low-visibility housing.

Preston Gannaway

A rooster darted from roof to roof. A canine symphony arose from behind the fences. “There should be a census for dogs,” Quezada remarked. Behind a yellow one-story house with a faded wood fence, they spotted a small garage next to an orange tree. It had two pipes for running water, which Sanjuan said meant it had been converted into a dwelling. Immigrants, particularly those who are undocumented, often live in such clandestine housing because they don’t have the credit to rent a conventional home or apartment. The house next door also had a converted garage in the backyard. Quezada marked the residences on her phone and sent the information through Facebook Messenger to the Census Outreach, an intermediary that would verify the data and eventually pass it along to the Census Bureau, which was cooperating with the pilot project in an effort to update addresses in advance of the 2020 census. “You have to go the extra mile to count people,” she said. “The average census worker isn’t going to go into the alleys like we do.”

Quezada and Sanjuan are both immigrants, but with very different backgrounds. Quezada, who is in her late 30s, fled war-torn El Salvador with her family in the 1980s after her father got a university research job in California. She has a doctorate in biology from the California Institute of Technology and worked for the State Department in Washington and the US Agency for International Development in Egypt before returning home and eventually taking a job with the collaborative. She wore a stylish tweed blazer and skinny jeans as she roamed the alleys and enthusiastically took photos of everything she saw, including a dead rat. Sanjuan, 43, came from Mexico when he was 17, and since then he’s barely left California and hasn’t attended school, apart from English-language classes. He wore a black “CA” baseball cap and a blue T-shirt. Having remodeled many unconventional structures as a construction worker, he was an expert at spotting hidden housing. Quezada compiled the data.

The census is America’s largest civic event, the only one that involves everyone in the country, young and old, citizen and noncitizen, rich and poor—or at least it’s supposed to. It’s been conducted every 10 years since 1790, when US Marshals first swore an oath to undertake “a just and perfect enumeration” of the population. The census determines how $675 billion in federal funding is allocated to states and localities each year for things like health care, schools, public housing, and roads; how many congressional seats and electoral votes each state receives; and how states will redraw local and federal voting districts. Virtually every major institution in America relies on census data, from businesses looking for new markets to the US military tracking the needs of veterans. The census lays the groundwork for the core infrastructure of our democracy, bringing a measure of transparency and fairness to how representation and resources are allocated across the country.

But with the Trump administration in charge, voting rights advocates fear the undercount could be amplified, shifting economic resources and political power toward rural, white, and Republican communities. The census is scheduled to begin on April 1, 2020, in the middle of the presidential election season. Of all the ways democracy is threatened under President Donald Trump—a blind eye to Russian meddling in elections, a rollback of voting rights, a disregard for checks and balances—an unfair and inaccurate census could have the most dramatic long-term impact. “It’s one of those issues that’s often the least sexy, least discussed in certain corners, and yet the ramifications for communities of color and vulnerable communities are so high in terms of what’s at stake for economic power and political power,” says Vanita Gupta, who led the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under President Barack Obama and now directs the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

A “perfect storm” is threatening the 2020 census, says Terri Ann Lowenthal, a former staff director for the House Subcommittee on Census and Population. Budget cuts enacted by the Trump administration and the Republican Congress forced the bureau to cancel crucial field tests in 2017 and 2018. The bureau’s director resigned last June, and the administration has yet to name a full-time director or deputy director. The next census will also be the first to rely on the internet. The Census Bureau will mail households a postcard with instructions on how to fill out the form online; if they don’t respond, it will send field-workers, known as enumerators, to knock on their doors. But in an effort to save money, there will be 200,000 fewer enumerators than in 2010, increasing the likelihood that households without reliable internet access will go uncounted. Enumerators will carry tablets instead of paper forms, and the reliance on technology raises cybersecurity fears in the wake of high-profile hacks and foreign election interference.

Juan, who lives in a rural area outside Kerman, California, known as Tijuanitas, carries his granddaughter as the family heads to a doctor’s appointment.

Preston Gannaway

“They’re putting together the census under a pall of uncertainty,” says Kenneth Prewitt, who directed the 2000 census. “How much money, who’s going to be in charge, what are we going to do on the core questionnaire itself? To do that under such a level of uncertainty is literally unprecedented.”

And then, on Monday night, the Trump administration dropped the biggest bombshell of all. The Commerce Department, which oversees the Census Bureau, announced that it would include a question about US citizenship on the census for the first time since 1950. Civil rights groups say the move will cause immigrants, particularly undocumented ones, to avoid responding to the census for fear of being reported to immigration authorities. The result will be a massive undercount of the Latino population, leading to reduced political power and federal resources for places like Fresno. The state of California, which has the country’s largest immigrant population, quickly filed a lawsuit against the administration over the question.

Sanjuan has been in the United States for 26 years and has a 12-year-old son who is a US citizen. He filled out the census for the first time in 2010, in part to ensure that his state and local governments received their share of federal funding for social programs. (California’s finance office estimates the state will lose $1,900 annually for each uncounted resident in 2020.) “The benefits weren’t really for me because I never ask for anything, but there are benefits that can help my son,” he told me at La Luna, a Mexican bakery in a working-class Latino neighborhood near the Yosemite Freeway, after a long afternoon canvassing Fresno’s alleys. In the run-up to the 2010 census, he helped conduct research on low-visibility housing in the San Joaquin Valley, an agricultural region that runs from Stockton in the north to Bakersfield in the south, with Fresno in the middle. He met farmworkers sleeping under trees near irrigation canals and urged them to respond to the census so they could receive better housing. “I’ve always said that they don’t have anything to fear because if [the government] really wanted to get rid of you, they would have done it a long time ago,” he said.

Percentage of the population under- and over-counted

Hispanic was not included as an option on the census before 1980.

Source: Census Bureau; compiled by Eli Day

But now undocumented immigrants are “much more fearful that they’re going to deport everyone,” he said. “They’ve arrested people in stores, at work, on buses.” He showed me a video posted to Facebook that day of Border Patrol agents searching for farmworkers in a field near the Mexican border. That week, Immigration and Customs Enforcement raided 77 businesses in Northern California, then the largest sweep since Trump became president. “California better hold on tight,” ICE Acting Director Thomas Homan told Fox News. “They’re about to see a lot more special agents, a lot more deportation officers.”

Sanjuan said it would be easier to persuade fellow immigrants to respond to the census if not for Trump. “I believe it’s going to be difficult to convince people now,” he told me.

In his first State of the Union address, Trump returned to familiar themes from his presidential campaign, decrying “open borders [that] have allowed drugs and gangs to pour into our most vulnerable communities.” Immigrants, he said, had stolen jobs from native-born Americans and “caused the loss of many innocent lives.” He highlighted the stories of families who’d lost children to the MS-13 gangs, and of the cops who’d battled them.

The next morning, 25 Latina women gathered for a monthly support group at the Fresno Center for New Americans, located in a strip mall next to a Family Dollar and an El Pollo Loco restaurant. They sat at a long U-shaped table beneath a mural of verdant farmland scenes that celebrated Fresno as “the best little city in the USA.”

A group of women share birthday cake after a community support group for Latinas in Fresno, California, in January.

Preston Gannaway

Quezada was there to give a presentation on the census. “I am an immigrant,” she said in Spanish, and she described how her family had escaped the civil war in El Salvador after the American-backed military regime falsely accused her father of being a communist. “When I was little, all I knew was war,” she said.

Quezada showed a slide of an ICE agent knocking on the door of a terrified woman. “You have the right to say nothing and also to ask to speak with your lawyer,” Quezada said. “This is [true] if you have documents or do not have documents.” The census, too, she said, “is a right that one should exercise. And it is a right that we all have as immigrants and as human beings.”

She asked how many of the women had participated in the census before. Only a few raised their hands. Maria, a farmworker who’d been in the United States for 37 years, said she’d filled out the form in 2010 but couldn’t convince her neighbors to do so. “They’re afraid,” she said. “They tell you, ‘They’re not going to count me. They only count people with documents. We thought we were going to be investigated.'” Her friends who received the form threw it in the trash, she added.

Adela, who came to Fresno 10 years ago, had never filled out a census form either. “You come not knowing the laws,” she said. “People say, ‘Oh, don’t fill it out because you don’t have insurance. You’re not here legally. As a result, you can’t fill it out. It doesn’t count. Even if you fill it out, it doesn’t count.'” She also recalled seeing 2010 census forms in trash cans in Fresno.

Quezada explained that California received $77 billion annually from the federal government, allocated according to census data, for programs that many people in the room used, like Head Start, English-language classes, and Medi-Cal public health insurance. If these 25 women were counted, she said, then over 10 years they would attract funding on the order of “half a million dollars, in this little room.” She added, “I hope you see the magnitude of the consequence of not participating.”

Francesca, a mother of four from Guerrero, Mexico, who had lived in Fresno for 18 years, raised her hand. She wanted to know why, despite staying at the same address in Fresno for 11 years, she didn’t receive a census form in 2010. “Almost everyone I know has never filled out a form,” she said. She wondered if that was one reason there weren’t enough teachers at her children’s schools and the classes were too large. (Census data helps school districts decide where to build new schools and hire teachers.)

Twenty percent of Californians live in hard-to-count areas like Fresno, where more than a quarter of all households failed to mail back their 2010 census forms, including a third of Latinos and African Americans, Quezada told the group. She pulled up a map showing that California contains 10 of the 50 counties in the country with the lowest census response rates. Those 10 counties are home to 8.4 million people; 38 states have smaller populations.

“There I am,” Francesca said, pointing at the map.

“Yes,” Quezada responded. “There you are.”

After the 2010 census failed to count 1.5 million US residents of color, the government might have been expected to devote more resources to ensure an accurate count. Instead, in 2012 Congress told the Census Bureau, over the Obama White House’s objections, to spend less money on the 2020 census than it had in 2010, despite inflation and the fact that the population was projected to grow by 25 million. After Trump took office, Congress cut the bureau’s budget by another 10 percent and gave it no additional funding for 2018, even though the census typically receives a major cash infusion at this juncture to prepare for the decennial count. (In late March, Congress allocated $1.3 billion in additional funding for the 2020 census, double what the Trump administration requested.)

The bureau’s director, John Thompson, testified on Capitol Hill in May 2017 that the budget cuts would force “difficult decisions.” A week later, he announced his resignation. The bureau canceled field tests last year in Puerto Rico and on Native American reservations in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Washington state that were designed to help the census reach hard-to-count communities. It then eliminated two of three “dress rehearsals” planned for April 2018, leaving Providence, Rhode Island, as the only site to test the bureau’s new technology before the 2020 census begins. (Rhode Island’s secretary of state says she’s received almost no communication from the bureau about the test.) Prewitt, the census director in 2000, compared the situation to the Air Force putting a new fighter plane into battle without testing it first. “You would never do that to the military,” he said, “but they’re doing that to the census.”

The Census Bureau has half as many regional centers and field offices today as it did in 2010. The Denver office oversees a region that stretches from Canada to Mexico. With the Boston office closed, the New York office covers all of New England. There are only two census outreach workers for all of the New York City metro area, according to Jeff Wice, a census expert at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government in New York. The first digital census may make the process more convenient for some people, but 36 percent of African Americans and 30 percent of Hispanics have neither a computer nor broadband internet at home, and a Pew Research Center survey published last year found that more than a third of Americans making less than $30,000 a year lack smartphones. In California’s Central Valley, “people aren’t just sitting around in a beaten-down trailer or an old motel on their laptop waiting to fill out their census form,” says Ilene Jacobs, director of litigation, advocacy, and training for California Rural Legal Assistance. (The Census Bureau will partially mitigate this issue by mailing paper questionnaires to the 20 percent of American households that have poor internet access.)

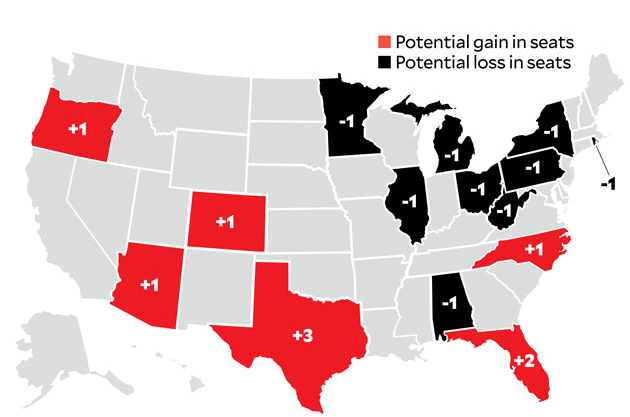

States expected to gain and lose congressional seats after 2020

These changes assume a fairly conducted census. A politicized one could distort the map.

Source: Election Data Services

Quezada and Sanjuan identified more than 600 unconventional structures in Fresno that could be sent census notices in 2020, increasing the number of housing units in the Census Bureau’s database by 6.3 percent in the areas they canvassed. But there will be fewer people dispatched by the bureau to count their occupants in person if they fail to respond, with the number of enumerators nationally dropping from more than 500,000 in 2010 to about 300,000 in 2020.

The technological shortcomings of the census are becoming apparent. Last year, the Government Accountability Office labeled it a “high risk” program and warned that the census website’s scheduled launch in April 2020 could resemble the disastrous HealthCare.gov rollout in 2010. The GAO found that only 4 of the bureau’s 40 technology systems had cleared testing, and none were ready to be used in the field.

Cybersecurity is also a major concern. Thompson says the bureau receives a “large number of attacks” every day. An internal review in January listed cybersecurity and public skepticism of the bureau’s ability to handle confidential data as the top two “major concerns that could affect the design or the successful implementation of the 2020 census.” The GAO has warned that “cyber criminals may attempt to steal personal information collected during and for the 2020 Decennial Census.” Hackers, including from Russia, could even seek to manipulate the overall count by breaking into the bureau’s databases.

Strong leadership could remedy some of these deficiencies, but there’s essentially no one steering the ship. Thompson announced his resignation on May 9, 2017, the same day FBI Director James Comey was fired. Thompson’s deputy, Nancy Potok, had already left to become the country’s chief statistician. The administration still hasn’t nominated anyone to replace them.

In November, Politico reported that Thomas Brunell, a professor of political science at the University of Texas-Dallas, would become the bureau’s deputy director, the position in charge of running the decennial census. Unlike past deputy directors, who were nonpartisan career civil servants with extensive census experience, Brunell had never worked in government. He had, however, written a 2008 book called Redistricting and Representation: Why Competitive Elections Are Bad for America, which provocatively argued that segregating voters by party affiliation in ultrasafe electoral districts offered them better representation than spreading them across competitive ones. He’d also been hired by Republicans in more than a dozen states as an expert witness in redistricting cases, defending some GOP-drawn maps that were later struck down by federal courts for racial gerrymandering.

The reports about Brunell sparked furious pushback from civil rights advocates. “It’s breathtaking to think they’re going to make that person responsible for the census,” former Attorney General Eric Holder told me. “It’s a sign of what the Trump administration intends to do with the census, which is not to take a constitutional responsibility with the degree of seriousness that they should. It would raise great fears that you would have a very partisan census.”

In February, Brunell withdrew from consideration. Yet the bureau has already become politicized. Last year, Trump installed Kevin Quinley, the former research director at Kellyanne Conway’s Republican polling firm, whose clients included Breitbart News, as a special adviser to the bureau. Quinley reports to the Office of White House Liaison at the Commerce Department, which reports to the White House, according to a former department official. “If something like that happened to me as a director, I would feel intimidated by it,” says Prewitt. In March, the bureau chose as its head of congressional affairs a top aide to former Sen. David Vitter (R-La.), who repeatedly introduced legislation to add a question about US citizenship to the census form.

The push to include a citizenship question on the 2020 census came from the Justice Department, which requested the change in December. The department said it needed the information to enforce the Voting Rights Act. Gupta, the former head of the department’s Civil Rights Division, says that’s “plainly a ruse to collect that data and ultimately to sabotage the census.” Six former directors of the bureau who served under Republican and Democratic presidents wrote a letter opposing the citizenship question. Steve Murdock, who led the census from 2008 to 2009 under President George W. Bush, told me, “It would be a horrendous problem for the Census Bureau and create all kind of controversies.” When I asked immigrants in the Fresno area whether they would respond to the census if it included a question about citizenship, virtually all of them said no.

RELATED: The 2020 Census Is a Cybersecurity Fiasco Waiting to Happen

Prominent anti-immigration hardliners, including Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, the former vice chair of Trump’s election integrity commission, are hoping to use citizenship data from the census to further reduce immigrants’ political influence. They have issued a radical proposal to draw legislative maps based on the number of citizens in a district rather than the total population, which would significantly diminish political representation for areas with large numbers of noncitizens.

Even before the Justice Department proposed the citizenship question, field surveys and focus groups conducted by the bureau in five states in 2017 found that “fears, particularly among immigrant respondents, have increased markedly.” Interviewees “intentionally provided incomplete or incorrect information about household members due to concerns regarding confidentiality, particularly relating to perceived negative attitudes toward immigrants,” according to a memo from the Center for Survey Measurement, a division of the bureau. One Spanish-speaking field representative told the bureau that a family moved away from a trailer park to avoid being interviewed: “There was a cluster of mobile homes, all Hispanic. I went to one and I left the information on the door. I could hear them inside. I did two more interviews, and when I came back they were moving…It’s because they were afraid of being deported.”

Such fear has precedent. During World War II, the Census Bureau gave the names and addresses of Japanese Americans to the Secret Service, which used the information to round up people and send them to internment camps. That abuse led to strict confidentiality standards for the bureau. But many immigrants will never trust the Trump administration with their personal information. “Immigrants and their families all feel under attack, under siege, by the federal government,” says Arturo Vargas, executive director of the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials Educational Fund, who serves on a Census Bureau advisory committee. “And then we have to turn around and tell these same people, ‘Trust the federal government when they come to count you.'”

Families listen to a presentation about the census at a low-income apartment complex in Huron, California, in February.

Preston Gannaway

The Commerce Department now estimates that only 55 percent of Americans will initially fill out the census in 2020 after receiving a postcard in the mail, down from 63 percent who sent back the first form in 2010. The need to reach out to the remainder of the population will drive up expenses and could result in further cutbacks. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who worked as an enumerator while attending Harvard Business School, told Congress in October that the census would cost $3 billion more than initially projected.

Already, the bureau’s outreach is lagging. For the 2010 census, it ran a $340 million promotional ad campaign featuring Winter Olympians, NASCAR drivers, and Dora the Explorer. “Everyone counts on the census form!” Dora said in one ad. The popular Telemundo telenovela Más Sabe el Diablo (“The Devil Knows Best”) even featured a storyline where the character Perla got a job working for the Census Bureau in New York City.

So far, the bureau has only 40 employees working with local governments and community groups on outreach, far short of the 120 at this point 10 years ago. The bureau is focusing its limited budget on perfecting the new technology it will use in 2020, shortchanging the advertising and local partnerships it typically uses to reach hard-to-count communities. (More than 30 private foundations—including the Oakland, California-based WKF Fund, which sponsored the outreach effort in Fresno—are attempting to fill the void and have raised $17 million to support community groups working on the census.) “They’re going to have to spend a lot of money to convince people it’s okay to be counted,” says Thompson. If the money isn’t there, “you’re not going to count everyone.”

After the 1990 census failed to count 4 million people—including 4.6 percent of African Americans, 5 percent of Hispanics, and 12 percent of Native Americans—the bureau issued a proposal to more accurately tally communities of color. It would use statistical sampling, which included detailed demographic data and survey research, to adjust the final census count and compensate for the demographic skew. That provoked a furious response from Republicans, who claimed sampling would be inaccurate and cost their party 24 seats in Congress and 410 seats in state legislatures. “At stake is our GOP majority in the House of Representatives as well as partisan control of state legislatures nationwide,” said Republican National Committee Chair Jim Nicholson. House Speaker Newt Gingrich sued the Census Bureau and took the case to the Supreme Court, which ruled 5-4 in his favor, even though, as Justice John Paul Stevens wrote in his dissent, “the use of sampling will make the census more accurate than an admittedly futile attempt to count every individual by personal inspection, interview, or written interrogatory.”

Mayor Rey León of Huron, California

Preston Gannaway

Brookings Institution demographer William Frey projects that in the 2020 census, for the first time, the white share of the population will fall below 60 percent. Trump, who won the white vote by 20 points in 2016, would stand to gain politically if the census were manipulated to slow that shift. Undercounting people of color would do the greatest harm to states like California, which has the most immigrants in the country. A significant undercount in 2020 could cost the state more than $20 billion over a decade and potentially one or two congressional seats and electoral votes. California is planning to spend $50 million over the next two years on outreach to hard-to-count populations.

“If we lose a congressional seat or two, our voice is minimized,” says state Rep. Joaquin Arambula, a Democrat from the Fresno area. “Our representation in the Electoral College is diminished. Our ability to influence who the next president is has changed. And it’s not reflective of what our democracy truly represents: one person, one vote.”

Some former directors of the census worry Republicans could simply choose to disregard the 2020 count. There’s precedent for that, too.

RELATED: How Voter Suppression Threw Wisconsin to Trump

Back in 1920, the census reported that for the first time, half the population lived in urban areas. Those results would have shifted 11 House seats to states with most of these new urban immigrants, who tended to vote Democratic. The Republican-controlled Congress recoiled. “It is not best for America that her councils be dominated by semicivilized foreign colonies in Boston, New York, and Chicago,” said Republican Rep. Edward Little of Kansas.

Congress refused to reapportion its seats using the 1920 census. Instead, it imposed drastic new quotas on immigration. It didn’t adopt a new electoral map until 1929.

There’s no indication Congress will ignore the results of the 2020 census. But Prewitt sees parallels between the Republican Congress of 1920 and the one today. “You could make a plausible argument that one party benefits from the current distribution of seats across the legislative bodies, and they can’t necessarily improve on the ratio they now have, so therefore why reapportion?” he says. “It’s unlikely, but not implausible.”

A day after canvassing the alleys of east Fresno, Quezada and Sanjuan drove me 30 miles south, past almond, pistachio, and orange fields. We reached a sprawling, unofficial trailer park, three miles square, inhabited by farmworkers and known as Tijuanitas.

Across the street from a grape field, we met a woman named Jacinta in front of her white trailer, next to a huge pile of abandoned refrigerators and tires. Her three children played by a plywood chicken coop in the backyard while her husband was out picking lettuce.

Mailboxes near Kerman and Huron, California

Preston Gannaway

Jacinta arrived 11 years ago from Oaxaca, Mexico, where she’d grown up speaking Triqui, an indigenous language. She doesn’t remember receiving a census form in 2010 and said that if anyone from the government came to Tijuanitas, she wouldn’t open the door. When Quezada asked whether she would fill out the census form if she received one, Jacinta responded, “I can’t read. How can I fill it out if I can’t read or write?”

Her next-door neighbor, a grape picker named Gilberto, had lived there for 20 years. A cage with two doves hung from a tree in his front yard; his work tools dangled from another. He was also from Oaxaca but spoke Mixtec, another indigenous language. When Quezada asked if he’d ever received the census form, Gilberto said no. “The census is for US citizens only,” he said. “If I received the form, I would return it because I’m not a US citizen.” Quezada told him the census counted noncitizens, too. “I didn’t know that,” Gilberto responded.

Tijuanitas isn’t visible from any major roads. It’s accessible only by a pothole-filled dirt road. It lacks safe drinking water and internet access, according to Quezada. Many residents have no street address and receive mail at PO boxes in nearby San Joaquin. From the perspective of the Postal Service or internet providers or utility companies, it’s as if Tijuanitas doesn’t exist. It appears ever likelier that the 2020 census will regard Tijuanitas and other underserved and neglected communities across the country the same way.