In late August, not 10 hours after a disgruntled former TV reporter posted video on Twitter and Facebook of himself gunning down two ex-colleagues in Virginia, the New York Daily News tweeted a preview of its front page for the next day. It featured a triptych of stills from the killer’s horrifying footage. Readers saw the attack from the shooter’s perspective—looking down the barrel of his Glock 19 at the flash of the muzzle and a victim’s terrified face, just moments before her death.

It was a gut punch to the victims’ loved ones. Journalists and the public responded with a torrent of tweets decrying the cover as “repulsive” and “despicable” and saying that “the victims deserve better.” The Daily News said that it published the images “to convey the true scale” of the attack “at a time when it is so easy for the public to become inured to such senseless violence.”

Journalism can be a powerful force for change, and news organizations should not flinch at reporting on mass shootings. But what the Daily News editors didn’t realize was that this sensational approach can possibly do more than perturb or offend. Such images provide the notoriety mass killers crave and can even be a jolt of inspiration for the next shooter.

The next one struck just five weeks later, in Oregon. The 26-year-old man who murdered nine and wounded nine others at Umpqua Community College last Thursday had posted comments expressing admiration for the Virginia killer, apparently impressed with his social-media achievement: “His face splashed across every screen, his name across the lips of every person on the planet, all in the course of one day. Seems like the more people you kill, the more you’re in the limelight.”

Since the 1980s, forensic investigators have found examples of mass killers emulating their most famous predecessors. Now, there is growing evidence that the copycat problem is far more serious than is generally understood. Ever since the 1999 massacre at Colorado’s Columbine High School, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has been studying what motivates people to carry out these crimes. Earlier this year, I met with supervisory special agent Andre Simons, who until recently led a team of agents and psychology experts who assist local authorities in heading off violent attacks around the country, using a strategy known as threat assessment. Since 2012, according to Simons, the FBI’s unit has taken on more than 400 cases—and has found evidence of the copycat effect rippling through many of them.

Evidence amassed by the FBI and other threat assessment experts shows that perpetrators and plotters look to past attacks both for inspiration and operational details, in hopes of causing even greater carnage. Would-be attackers frequently emulate the Columbine massacre; one high-level law enforcement agent told me that he’s encountered dozens of students around the country who say they admire the Columbine killers. “Some of these kids now weren’t even born when that happened,” he said. The 2007 massacre at Virginia Tech and other attacks that generated major publicity have also spawned many copycats, according to several law enforcement officials I spoke with.

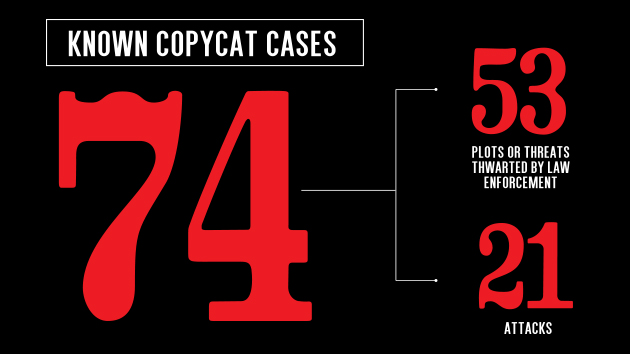

As part of our investigation into threat assessment, Mother Jones documented the chilling scope of the “Columbine effect”: We found at least 74 plots and attacks across 30 states in which suspects and perpetrators claimed to have been inspired by the nation’s worst high school massacre. Their goals ranged from attacking on the anniversary of Columbine to outdoing the original body count. Law enforcement stopped 53 of these plots before anyone was harmed. Twenty-one of them evolved into attacks, with a total of 89 victims killed, 126 injured, and nine perpetrators committing suicide. (See more about this data here.)

As they plan to strike, many mass shooters now express their desire for fame in comments and manifestos posted online. “They do this to claim credit and to articulate the grievance behind the attack,” Simons told me. “And we believe they do it to heighten the media attention that will be given to them, the infamy and notoriety they believe they’ll derive from the event.”

Despite whatever delusions or obsessive grievances they may be experiencing, many perpetrators are keenly aware of how their actions will be seen by the media and the public. “A lot of times they thrive on posing,” says Reid Meloy, a forensic psychologist at the University of California-San Diego and a leading researcher on targeted violence who has interviewed and evaluated mass killers. He cites the police booking photo of Jared Loughner, who shot Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and 18 others in Tucson, Arizona, in 2011. “He’s got that contemptuous smile, like it’s a great pose. The savvy of these individuals to capitalize on visual exposure should not be underestimated.”

A month before the Tucson rampage, Loughner posted what he called “a foreshadow” of his attack in comments on his MySpace page: “I’ll see you on National TV!” He got what he wanted—and then some. His booking photo “flashed around the world, at once haunting and fascinating,” Washington Post media reporter Paul Farhi wrote three days after the massacre. “Dozens of newspapers placed the photo atop their front pages, burning Loughner’s visage into the American consciousness.” (The Daily News ran a “nearly life-sized” version on its front page, Farhi noted, with the headline “Face of Evil,” while the New York Post ran a similar front page that blared “Mad Eyes of a Killer.”) Several of the nation’s largest news outlets have continued using the image in stories and broadcasts ever since.

The media faces a growing challenge in how its content is spread and recycled. When I asked various law enforcement and forensic psychology experts what might explain America’s rising tide of gun rampages, I heard the same two words over and over: social media. Although there is no definitive research yet, widespread anecdotal evidence suggests that the speed at which social media bombards us with memes and images exacerbates the copycat effect.

Meloy and other threat assessment experts recommend some specific changes by the news media to address the copycat problem. Attackers’ names should be used minimally—and their images even less so. “Their use can have a dangerous effect on other young men vulnerable to dark and violent identifications with the perpetrators,” Meloy says. “When real life for these individuals is so blighted in terms of love and work, they turn to the anti-heroes.” The narcissism running through many copycat cases is even more troubling in this regard: “They don’t just want to be like them—they are envious and want to one-up them,” Meloy explains. Copycats will aim to accomplish that either by going for a higher body count, he says, or, as in the Virginia case, killing in a more sensational way.

Meloy argues the media should also rethink some of its language. “Stop using the term ‘lone wolf’ and stop using ‘school shooter,'” he says. “In the minds of young men this makes these acts of violence cool. They think, ‘This has got some juice behind it, and I can get out there and do something really cool—I can be a lone wolf. I can be a shooter.'” Instead, Meloy suggests using terms such as “an act of lone terrorism” and “an act of mass murder.”

Changing how the media covers these stories may be especially important when it comes to preventing gun rampages in schools, according to John Van Dreal, a psychologist who helped build a pioneering threat assessment program in Oregon’s Salem-Keizer school district, which has more than 40,000 students. “I hear how all the kids talk about it,” Van Dreal says. “When it gets played up so much in the media, it becomes heroic to the kids who are thinking about doing it.” No one can control what explodes across social media platforms. But news organizations remain powerful magnifiers of content and could work toward “an ethical best practice to leave out the imagery and the name as much as possible,” Van Dreal says.

In January, Caren and Tom Teves—whose son Alex was one of the 12 people murdered in the July 2012 massacre in Aurora, Colorado—launched a “No Notoriety” campaign admonishing the media never to use mass shooters’ names. There is a similar movement stirring among police officers: The Oregon sheriff handling the response to last week’s attack (whose views on gun regulations and the Sandy Hook massacre raised some eyebrows) vowed in a press conference that he would not say the shooter’s name—and the town of Roseburg rallied around the idea. His move echoed the recommendations of a FBI-endorsed law enforcement training program on active shooters at Texas State University, which recently began a “Don’t Name Them” campaign.

Though laudable, such absolutism is unrealistic in terms of the media’s duty to report. As the Poynter Institute’s chief media correspondent Jim Warren explained Sunday on CNN’s Reliable Sources, reporting on the killers is crucial to public understanding of the problem—and for knocking down the rampant misinformation that ricochets around the internet in the aftermath of an attack. (Rumors swirled late last week that the Umpqua killer was a Muslim, for example, which was false.)

But some journalists and news organizations are beginning to recast their coverage of mass shooters with the recognition that they should avoid glamorizing them, and that proportionality matters. The day of the Virginia murders, CNN said it would show a segment of the killer’s footage only once per hour; if that sounded odd in its own right, it was an improvement over the sensationalism of the constant looping so common on cable news networks. Since Aurora, CNN’s Anderson Cooper has at times declined to name on the air the perpetrators of high-profile massacres.

Should the media refrain from naming/showing mass shooters? @SFClem and Tom & @CarenTeves say yes: http://t.co/an2IPDyxUh from Sunday’s show

— Brian Stelter (@brianstelter) October 5, 2015

There is precedent for establishing the type of industry standard that threat assessment experts suggest. Rape victims and juveniles charged with crimes are rarely named in news reports. Ditto people who commit suicide—another problem with a potent contagion effect. When American journalists are taken hostage overseas, news organizations usually agree not to report on their plight due to fears that it would undermine their safety and jeopardize negotiations for their release. Perhaps a rising awareness of the copycat problem will lead to a similar change in how the media covers gun rampages.

Over the past three years, a team of colleagues at Mother Jones and I have spent a great deal of time and effort reporting on mass shootings. Knowing what we do now, we’ll continue to inform the public while avoiding what could contribute to the copycat problem. In light of the Umpqua attacker’s quest for notoriety, we’ve chosen not to publish his image or put his name in any headlines. We will focus attention on him or other killers only when we see clear journalistic value in doing so.

We made similar choices with our newly published cover package on threat assessment and the Columbine effect. With most of our major investigations into gun violence, we have published our underlying datasets so that anyone can use them for further study and analysis. But we are only providing summary data and analysis from our research on Columbine copycats. Though much of the case-level data we’ve collected is publicly available, we decided not to make it easily accessible in one place, where it could potentially be used by aspiring attackers searching for inspiration or tactical information.

Below, we’ve compiled a set of recommendations based on interviews with and research from threat assessment experts concerned about this issue. Not all of these ideas will go over well in newsrooms, and as journalists, we can see arguments for and against these practices. But given the scope of the copycat problem, they are worthy of serious consideration and debate. [Ed. note: For more on that debate, see Follman’s opinion piece in the New York Times.]

7 ways the media can help reduce the copycat effect

Report on the perpetrator forensically and with dispassionate language. Avoid terms like “lone wolf” and “school shooter,” which may carry cachet with young men aspiring to attack. Instead use language such as “perpetrator,” “lone act of terrorism,” and “act of mass murder.”

Keep the perpetrator’s name out of headlines. Rarely, if ever, will a generic reference to him in a headline be any less practical.

Minimize use of the perpetrator’s name. When it isn’t necessary to repeat it, don’t. (And don’t include middle names gratuitously, a common practice for distinguishing criminal suspects from others of the same name, but which can otherwise lend a false sense of their importance.)

Minimize use of images of the perpetrator. This is especially important, both in terms of aspiring attackers’ desire for fame and the psychology of individuals who may be vulnerable to identifying with mass shooters.

Avoid using “pseudocommando” or other posed photos of the perpetrator. Such self-styled images, commonly posted on social media, are the ones they hope will get publicity. These should be avoided especially after the images are outdated, such as showing the Aurora killer with his “Joker” hair during his trial three years after the attack, when he was heavier and wore glasses and a beard.

Avoid publishing the perpetrators’ videos or manifestos except when clearly valuable to the reporting. Instead, paraphrase, cite sparingly, and provide analysis. The guiding question here may be: Is this evidence already easily accessible online? If so, is there a genuine reason to reproduce it in full and spread it, other than to generate page views?

Don’t fixate on body counts. Would-be attackers are keeping score too—and many want to outdo their predecessors.

This story has been updated.