Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the Los Angeles Times.

It’s not a matter of if, but when and where the next mass shooting will happen: It might take place at another shopping mall, or college campus, or suburban office building, and probably not long from now. Yet, as these disturbing incidents keep appearing in the headlines, various commentators have argued that mass shootings are not on the rise.

That may be true if you look at all mass shootings, including gang killings and in-home violence stemming from domestic abuse. But new research from the Harvard School of Public Health demonstrates that mass shootings in public have become far more frequent. The Harvard findings are also corroborated by a separate report issued recently by the FBI.

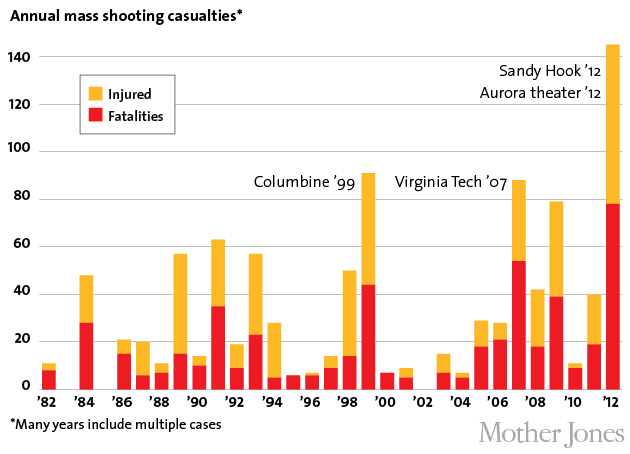

After a heavily armed young man gunned down 12 people and wounded 58 others at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, in July 2012, my colleagues at Mother Jones and I began examining how often mass shootings in public places occurred. Finding no reliable answer, we set about gathering three decades of data. We discovered that such shootings were on the rise—even before the horror at Sandy Hook Elementary, the Washington Navy Yard, Ft. Hood, and near UC-Santa Barbara.

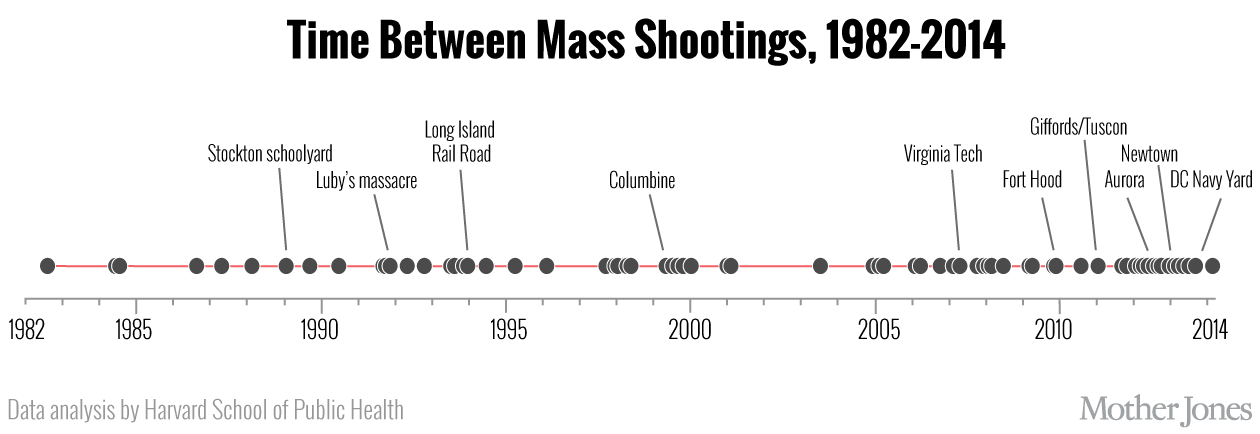

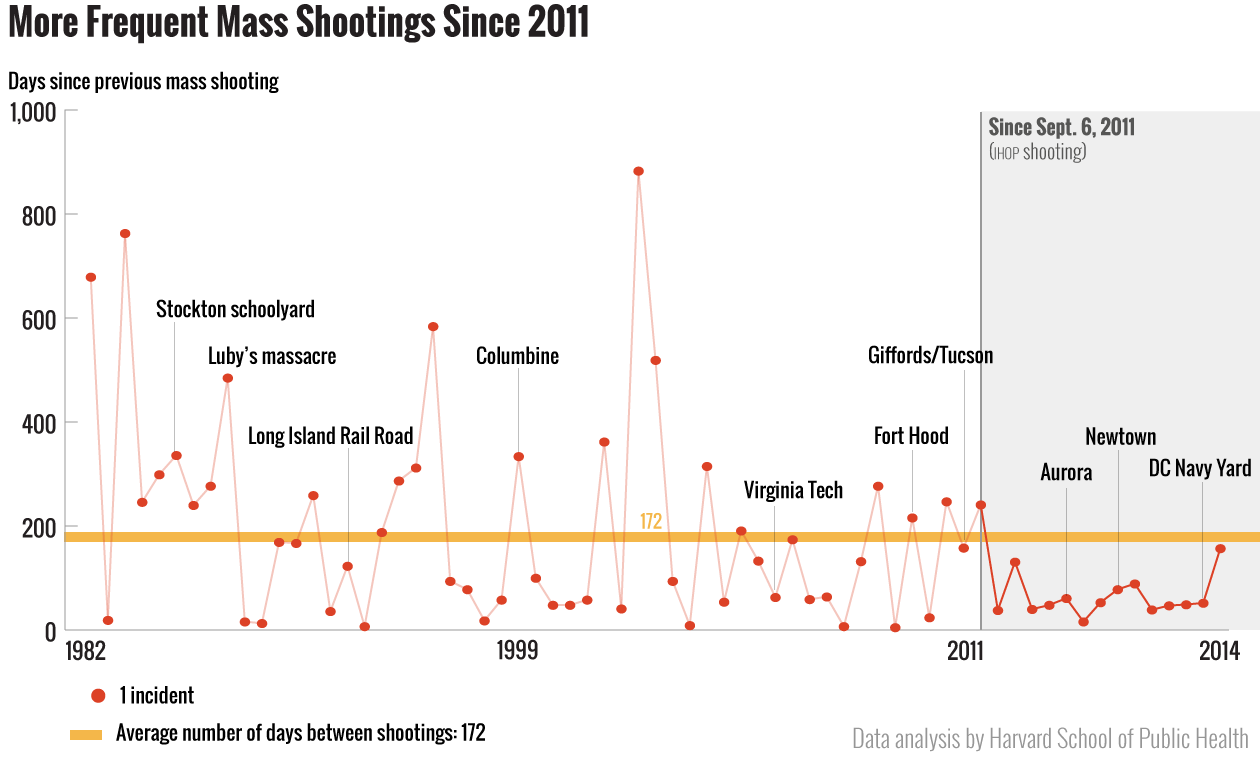

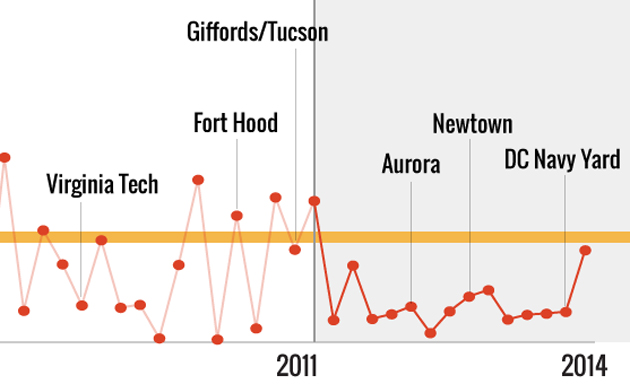

Though mass shootings make an outsize psychological impact, they are a tiny fraction of the nation’s overall gun violence, which takes more than 30,000 lives annually. Rather than simply tallying the yearly number of mass shootings, Harvard researchers Amy Cohen, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller determined that their frequency is best measured by tracking the time between each incident. This method, they explain, is most effective for detecting meaningful shifts in relatively small sets of data, such as the 69 mass shootings we documented. Their analysis of the data shows that from 1982 to 2011, mass shootings occurred every 200 days on average. Since late 2011, they found, mass shootings have occurred at triple that rate—every 64 days on average. (For more details on their analytical method, see this related piece.)

There has never been a clear, universally accepted definition of “mass shooting.” The data we collected includes attacks in public places with four or more victims killed, a baseline established by the FBI a decade ago. We excluded mass murders in private homes related to domestic violence, as well as shootings tied to gang or other criminal activity. (Qualitative consistency is crucial, even though any definition can at times seem arbitrary. For example, by the four-fatalities threshold neither the attack at Ft. Hood in April nor the one in Santa Barbara in May qualifies as a “mass shooting,” with three victims killed by gunshots in each incident.) A report from the FBI on gun rampages, issued in late September, includes attacks with fewer than four fatalities but otherwise uses very similar criteria.

The FBI report, which includes 160 “active shooter” cases between 2000 and 2013, notes explicitly that it is not a study of mass shootings. Rather, it analyzes incidents in which shooters are “actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people” in a public place, regardless of the number of casualties. But within the FBI’s 160 cases is a subset of 44 mass shootings (in which four or more were murdered) nearly identical to Mother Jones‘ data set from the same time period. The Harvard researchers underscore that the FBI had access to law enforcement sources that Mother Jones did not: “That the results of the two studies are so similar reinforces our finding that public mass shootings have increased.”

James Alan Fox, a widely cited criminologist from Northeastern University, has argued that mass shootings are not on the rise, and that they are too rare to merit significant policy changes. As he put it recently in an interview with CNN’s Jake Tapper: “We treasure our personal freedoms in America, and unfortunately, occasional mass shootings, as horrific as they are, is one of the prices that we pay for the freedoms that we enjoy.”

But in drawing his conclusions, Fox relies on overly broad data. His study is misguided, the Harvard researchers say, because it conflates public mass shootings with a larger set of mass murders that are “contextually distinct,” primarily those in private homes. According to data compiled by USA Today, there have been at least 95 domestic-violence-related mass shootings since 2006 alone. These crimes are no less awful (and we’ve reported on them too). But mass murders in schools and shopping malls are a different monster in terms of impact on public safety and the complicated policy questions they raise—not least how they might be stopped.

In response to the Harvard research, Fox insisted that mass shootings should not be distinguished categorically by their circumstances. “To the victims who are slain, it hardly matters whether they were killed in public or in a private home,” he told the Huffington Post. “Nor does it matter if the assailant was a family member or a stranger. They are just as dead.”

But the question of whether public mass shootings can be prevented hinges on understanding the complex factors behind them—which starts with tracking these shootings accurately. That, at least, is a role that the federal government is poised to assume: Last year President Obama signed the Investigative Assistance for Violent Crimes Act, which authorizes the Department of Justice to investigate mass shootings in public places. Notably, the law defines the threshold for these crimes as three or more people killed—which means eventually we’ll have data showing that the scope of the problem is far greater than we’ve already seen.

For more of Mother Jones’ reporting on guns in America, see all of our latest coverage here, and our award-winning special reports.