Soon after the school year started in September 2000, a police officer working at McNary High in Keizer, Oregon, got a tip about a junior named Erik Ayala. The 16-year-old had told another student that “he was mad at ‘preps’ and was going to bring a gun in.” Ayala struck the officer as quiet, depressed. He confided that “he was not happy with school or with himself” but insisted he had no intention of hurting others. Two months later, Ayala tried to kill himself by swallowing a fistful of Aleve tablets. He was admitted to a private mental health facility in Portland, where he was diagnosed with “numerous mental disorders,” according to the police officer’s report.

To most people, Ayala’s suicide attempt would have looked like a private tragedy. But for a specialized team of psychologists, counselors, and cops, it set off alarm bells. They were part of a pioneering local program, launched after the Columbine school massacre the prior year, to identify and deter kids who might turn violent. Before Ayala was released from the hospital, the Salem-Keizer school district’s threat assessment team interviewed his friends, family, and teachers. They uncovered additional warning signs: In his school notebooks, Ayala had raged about feeling like an outsider and being rejected by a girl he liked. He had repeatedly told his friends that he despised “preps” and wished he could “just go out and kill a few of them.” He went online to try to buy a gun. And he’d drawn up a hit list. The names on it included his close friend Kyle, and the girl he longed for.

The threat assessment team had to decide just how dangerous Ayala might be and whether they could help turn his life around. As soon as they determined he didn’t have any weapons, they launched a “wraparound intervention”—in his case, counseling, in-home tutoring, and help pursuing his interests in music and computers.

“He was a very gifted, bright young man,” recalls John Van Dreal, a psychologist and threat assessment expert involved in the case. “A lot of what was done for him was to move him away from thinking about terrible acts.”

As the year went on, the team kept close tabs on Ayala. The school cops would strike up casual conversations with him and his buddies Kyle and Mike so they could gauge his progress and stability. A teacher Ayala admired would also do “check and connects” with him and pass on information to the team. Over the next year and a half, the high schooler’s outlook improved and the warning signs dissipated.

When Ayala graduated in 2002, the school-based team handed off his case to the local adult threat assessment team, which included members of the Salem Police Department and the county health agency. Ayala lived with his parents and got an IT job at a Fry’s Electronics. He grew frustrated that his computer skills were being underutilized and occasionally still vented to his buddies, but with continued counseling and a network of support, he seemed back on track.

The two teams “successfully interrupted Ayala’s process of planning to harm people,” Van Dreal says. “We moved in front of him and nudged him onto a path of success and safety.”

But then that path took him to another city 60 miles away, where he barely knew anyone.

This past August, I traveled to Disneyland to join more than 700 law enforcement agents, psychologists, and private security experts from around the country at the annual conference of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals. While families splashed in the Disneyland Hotel’s pools and strolled to the nearby theme park, conference attendees sat in chilly ballrooms for sessions like “20 Years of Workplace Shootings” and “Evil Thoughts, Wicked Deeds.”

After a day of talks focused on thwarting stalkers and preventing the next Sandy Hook, it seemed incongruous to emerge to throngs of overexcited kids and their weary parents enjoying the nightly fireworks. But it is no coincidence that Disney plays host to this conference. As gun rampages have increased, so have security efforts at public venues of all kinds, and threat assessment teams can now be found everywhere from school districts and college campuses to corporate headquarters and theme parks. Behind the scenes, the federal government has ramped up its threat assessment efforts: Behavioral Analysis Unit 2, a little-known FBI team based in Quantico, Virginia, now marshals more than a dozen specialists in security and psychology from across five federal agencies to assist local authorities who seek help in heading off would-be killers. Those calls have been flooding in: Since 2012, the FBI unit has taken on more than 400 cases.

The conference keynote was given by Reid Meloy, a tall, white-haired forensic psychologist from the University of California-San Diego who is a leading researcher in the field. His presentation was peppered with gallows humor—a clip from Breaking Bad, a photo of Jack Nicholson “playing himself” in The Shining—and professional koans. “Monitor your own narcissism,” he warned the assembled investigators. “This is going to be easier for some of you to get than others,” he quipped, flashing an image of Donald Trump.

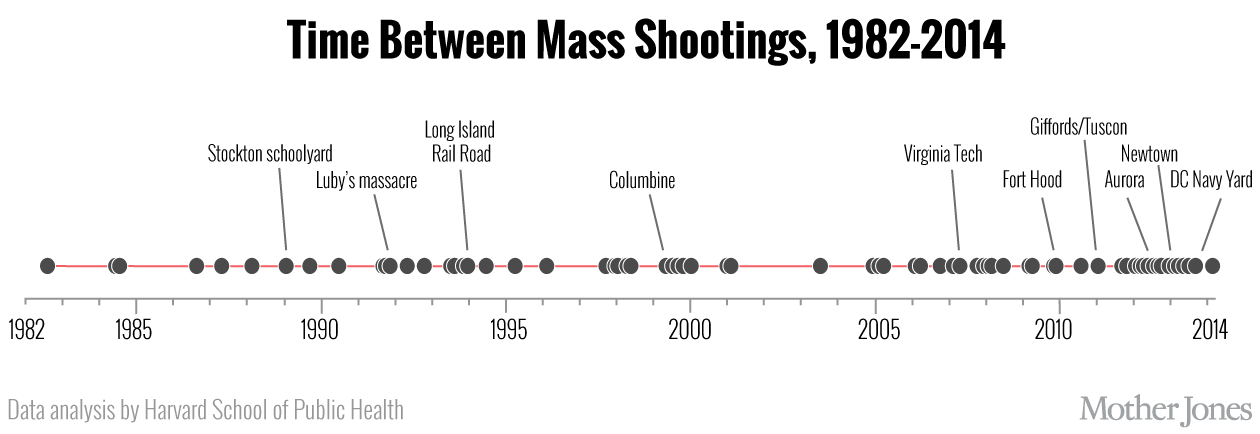

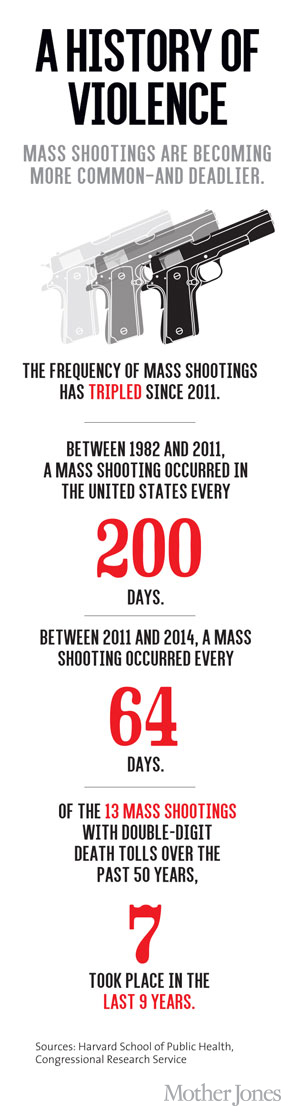

There was a simple reason, Meloy suggested, for the record number of people packing the room: Mass murder is on the rise. “We’ve seen this very worrisome pattern over the past five or six years of an increase in targeted violence in public places,” he told me later. “Personally and professionally, this is a big concern—that uptick is very important, especially as violent crime has decreased.”

Threat assessment is essentially a three-part process: identifying, evaluating, and then intervening. A case usually begins with a gut feeling that something is off. A teacher hears a student’s dark comments and alerts the principal, or someone gets freaked out by a coworker’s erratic behavior and tells a supervisor. If the tip makes its way to a local threat assessment team, the group quickly analyzes the subject’s background and circumstances. They may talk with family, friends, or coworkers to get insight into his intentions, ability to handle stress, and, most importantly, potential plans to strike. “One of the first things you focus on with this process is access to weapons,” Meloy notes. Like the group that handled Ayala’s case, the team draws on mental health and security expertise. Possible responses range from helping the subject blow off steam and refocus on school or work to providing longer-term counseling. If violence seems imminent, involuntary hospitalization or arrest may be the safest approach.

But such drastic measures are rare. “With a lot of these cases, you peel back the curtain and there are good social and mental health interventions that are diverting the person onto a better course,” Meloy says. Often the best initial step is the most direct—conducting a “knock and talk” interview, which has the dual benefit of offering help and putting the subject on notice. Simply realizing that authorities are watching can be an effective deterrent.

Threat assessment requires a remarkable shift in thinking for law enforcement because in most cases no crime has occurred. “Our goal is prevention over prosecution,” supervisory special agent Andre Simons, who led the FBI unit until this summer, explained when we met at the bureau’s headquarters in Washington earlier this year. “If we can facilitate caretaking for individuals who are not able to perceive alternatives to violence, then I think that’s a righteous mission for us.”

Ever since Columbine, the FBI has been studying what drives people to commit mass shootings. Last fall it issued a report on 160 active-shooter cases, and what Simons could disclose from its continuing analysis was chilling: To a much greater degree than is generally understood, there’s strong evidence of a copycat effect rippling through many cases, both among mass shooters and those aspiring to kill. Perpetrators and plotters look to past attacks for not only inspiration but operational details, in hopes of causing even greater carnage. Emerging research—including our own analysis of the “Columbine effect“—could have major implications for both threat assessment and how the media should cover mass shootings.

In October 2013, then-Attorney General Eric Holder announced that Simons’ FBI unit had helped prevent almost 150 attacks in one year. The nearly two dozen experts I spoke with didn’t like to be so definitive, noting that it’s impossible to prove a negative. But many cited cases in which they believed threat assessment teams had prevented great harm. Sergeant Jeff Dunn, who leads the Los Angeles Police Department’s Threat Management Unit, described a firefighting recruit who became enraged when he failed out of the academy. “He told another recruit, ‘When they fire me, I’m gonna come back here and fucking massacre everyone.'” Academy officials alerted the LAPD, and Dunn’s unit got a search warrant for the recruit’s home. “This guy was absolutely geared to go to war,” Dunn said. His arsenal included nearly a dozen semi-automatic handguns and assault rifles and a homemade explosive device. “Had there not been an intervention of some sort,” Dunn said—in this case, an arrest on a felony weapons charge—”I have no doubt that it would’ve resulted in an active-shooter scenario.”

But cases often aren’t so clear. One of the biggest challenges for threat assessment teams is that sometimes the quieter, less outwardly threatening subjects can prove the most dangerous. “When there are individuals who prompt a sense of anxiety or fear but no law or policy has been broken,” Simons says, “that’s the real work.” Of the hundreds of subjects tracked by the FBI unit, he told me, only one went on to injure somebody. But measuring the effectiveness of threat assessment is tricky because ultimately there is no way of knowing whether someone would have otherwise gone on to attack.

Meloy compares the challenge to fighting cardiovascular disease: Doctors can’t predict whether someone will have a heart attack, but they can do a lot to decrease the risk. “You try to lower the probability.”

When the next shooting happens at a school, an office building, or a movie theater, the question will again be asked: “What made him snap?” But mass murder is not an impulsive crime. Forensic investigations show that virtually every one of these attacks is a predatory crime, methodically planned and executed. Therein lies the promise of threat assessment: The weeks, months, or even years when a would-be killer is escalating toward violence are a window of opportunity in which he can be detected and thwarted.

A growing body of research has shed light on this “pathway to violence.” It often begins with an unshakable sense of grievance, which stirs thoughts about harming people and leads to the planning and preparation for an attack. Elliot Rodger, convinced that women were unfairly denying him sex, seethed for months and fantasized about a “day of retribution” before he bought firearms, scouted sorority houses, and went on to kill 6 people and injure 14 others near Santa Barbara, California, in May 2014.

A confluence of behaviors can indicate that someone is poised to walk into a school or a shopping mall and open fire. These include an obsession with weapons, a fixation on images of violence, and a history of aggressive acts that aren’t directly related to the planned attack—possibly a way for the perpetrator to test his resolve. Almost a year before Rodger struck, he attempted to push some women off a 10-foot ledge at a house party. Some killers have mutilated pets before going on rampages.

In fact, the vast majority of mass shooters signal their intentions in advance, though usually not directly to their intended targets. This “leakage,” as threat assessment experts call it, can be difficult to recognize. Before Dylann Roof murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, he told a friend about his desire to kill people and start a race war. (The friend claimed he didn’t think Roof was serious.) Weeks before Rodger attacked, he posted disturbing videos that prompted his mother to alert a county mental health agency that he was suicidal. In response, sheriff’s deputies went to Rodger’s apartment to do a welfare check, interviewing him just a few strides from where he’d stashed three handguns and hundreds of rounds of ammunition. He persuaded them he was fine. “Thankfully, all suspicion of me was dropped,” he later wrote, “and the police never came back.”

We know that many mass shooters are young white men with acute mental health issues. The problem is, such broad traits do little to help threat assessment teams identify who will actually attack. Legions of young men love violent movies or first-person shooter games, get angry about school, jobs, or relationships, and suffer from mental health afflictions. The number who seek to commit mass murder is tiny. Decades of research have shown that the link between mental disorders and violent behavior is small and not useful for predicting violent acts. (People with severe mental disorders are in fact far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators.)

That’s why sizing up a suspect’s current circumstances is crucial: Did he recently get fired from a job? Did he lose his kids in a nasty custody battle? Is he failing out of school or abusing drugs? Investigators also look for visible signs such as deteriorating hygiene or living conditions, which is why approaching someone directly and building rapport can be so important.

“Most people who have a psychotic episode aren’t thinking violently,” explains Mario Scalora, a forensic psychologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. But for those who are experiencing psychosis—including 80 percent of stalkers who target public figures—intervention can head off disaster. Scalora describes the case of a student he calls Bob who experienced a psychotic break in his early 20s. Scalora’s campus threat assessment team grew concerned after getting a tip about Bob muttering to himself and making ominous comments. They sent plainclothes detectives to his residence, where on the wall of his room hung a grotesque theater mask whose mouth had been sewn shut with black string. Bob said that voices were commanding him to hurt people at the behest of God, and that he was scared. The detectives persuaded him to check into a psychiatric ward for evaluation. “This made him feel cared for,” Scalora says, “and gave us a mechanism by which we could continue to manage him. By building rapport with him, we’re learning a lot about him and getting rich assessment data, and in the meantime he’s not stalking people on our campus. It’s a win-win.”

When the lead detective followed up with Bob a couple of days into his hospital stay, he asked her, “Can you go to my room and get the mask, and this big knife that’s under my bed? I don’t want them anymore.”

The concept of cops and mental health experts working hand in hand to stop violent crimes before they occur is relatively new. Its origins trace in part to a summer morning in West Los Angeles. Shortly after 10 a.m. on July 18, 1989, a 21-year-old actress named Rebecca Schaeffer was getting dressed for a meeting with Francis Ford Coppola about a role in the next Godfather movie when her apartment buzzer sounded. The intercom was broken, so Schaeffer went to the front door, where a young man stood holding a shopping bag. Nineteen-year-old Robert Bardo had been trying to reach Schaeffer for two years, writing her fan letters and periodically taking a bus from Tucson to LA to look for her. He’d never been able to get onto the soundstage where Schaeffer filmed the sitcom My Sister Sam, but he’d finally found her address.

Bardo had already dropped by that morning, according to his own account, and Schaeffer had chatted with him politely. But now she was anxious. “You came to my door again,” she said. “Hurry up, I don’t have much time.” Bardo later recalled, “I thought that was a very callous thing to say to a fan.” In his bag he had a letter and a CD he wanted to give her. He also had a .357 Magnum handgun. A neighbor heard Schaeffer scream as Bardo fired a single shot into her chest.

Until then, obsessive behavior that could turn violent was still widely viewed as a mental health issue beyond the purview of law enforcement, even after the attacks on John Lennon and Ronald Reagan and a spate of government workers “going postal.” But Schaeffer’s murder shocked Hollywood, and studio heads called for action by the LAPD, which was already frustrated by its inability to stop a string of stalking murders of nonfamous women. The LAPD devised a plan for a multidisciplinary team that would aim to head off such crimes.

The LAPD Threat Management Unit’s mission expanded in 1995 after a city electrician, angry about a poor performance evaluation, walked into the Piper Tech center downtown and shot four supervisors to death. “Piper Tech” became shorthand for the rising wave of workplace threats the unit began to confront. (It currently handles about 200 cases a year, roughly half of which are workplace related.) Meanwhile, in Washington, DC, the Secret Service had also been developing tenets of threat assessment, led by a former agent from Reagan’s security detail. But for most cops, close collaboration with mental health experts remained unheard of. And the idea of intervening before there was a crime to investigate went against everything they knew from their training. “It requires a paradigm shift,” says the LAPD’s Dunn. “So many in law enforcement don’t recognize how useful a tool this can be.”

Then came Columbine.

As they plotted for months to slaughter their classmates, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold weren’t just driven by rage and depression—they wanted to be immortalized and to inspire future school shootings. In diary entries and videos, the duo fantasized about Hollywood directors fighting over their story. They filmed themselves firing guns and yelling into the camera about killing hundreds and starting a “revolution.”

Such “legacy tokens” now often include manifestos posted online by perpetrators. “They do this to claim credit and to articulate the grievance behind the attack,” says the FBI’s Simons. “And we believe they do it to heighten the media attention that will be given to them, the infamy and notoriety they believe they’ll derive from the event.”

There has long been evidence that stalkers and mass murderers emulate their famous predecessors. Before Bardo gunned down Schaeffer, he sent a letter to Mark Chapman, imprisoned for the 1980 murder of John Lennon. When Bardo fled from Schaeffer’s building, among the items he discarded was a copy of The Catcher in the Rye, the novel Chapman infamously sat down to read after shooting Lennon. John Hinckley Jr. had a copy of the book and a John Lennon photo calendar in his hotel room when he tried to assassinate Reagan in 1981. Forensic psychologists describe this phenomenon as following a “cultural script,” or the “Werther effect,” referring to a spate of copycat suicides in 18th-century Europe after the publication of Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther.

The Columbine killers authored a grimly compelling new script at the dawn of the internet age. Sixteen years later, the Columbine legacy keeps reappearing in violent plots, driven in part by online subcultures that obsess over the duo’s words and images. “It’s a cult following unlike anything I’ve ever seen before,” says one longtime security specialist.

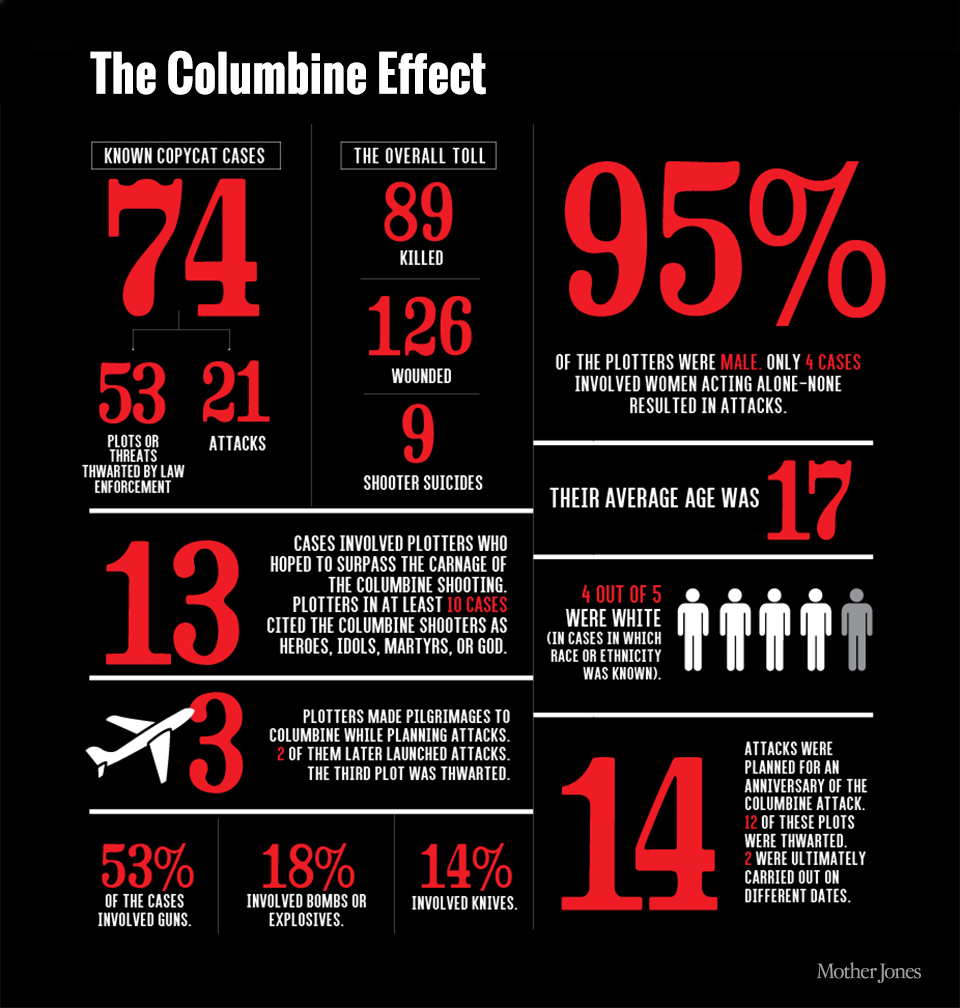

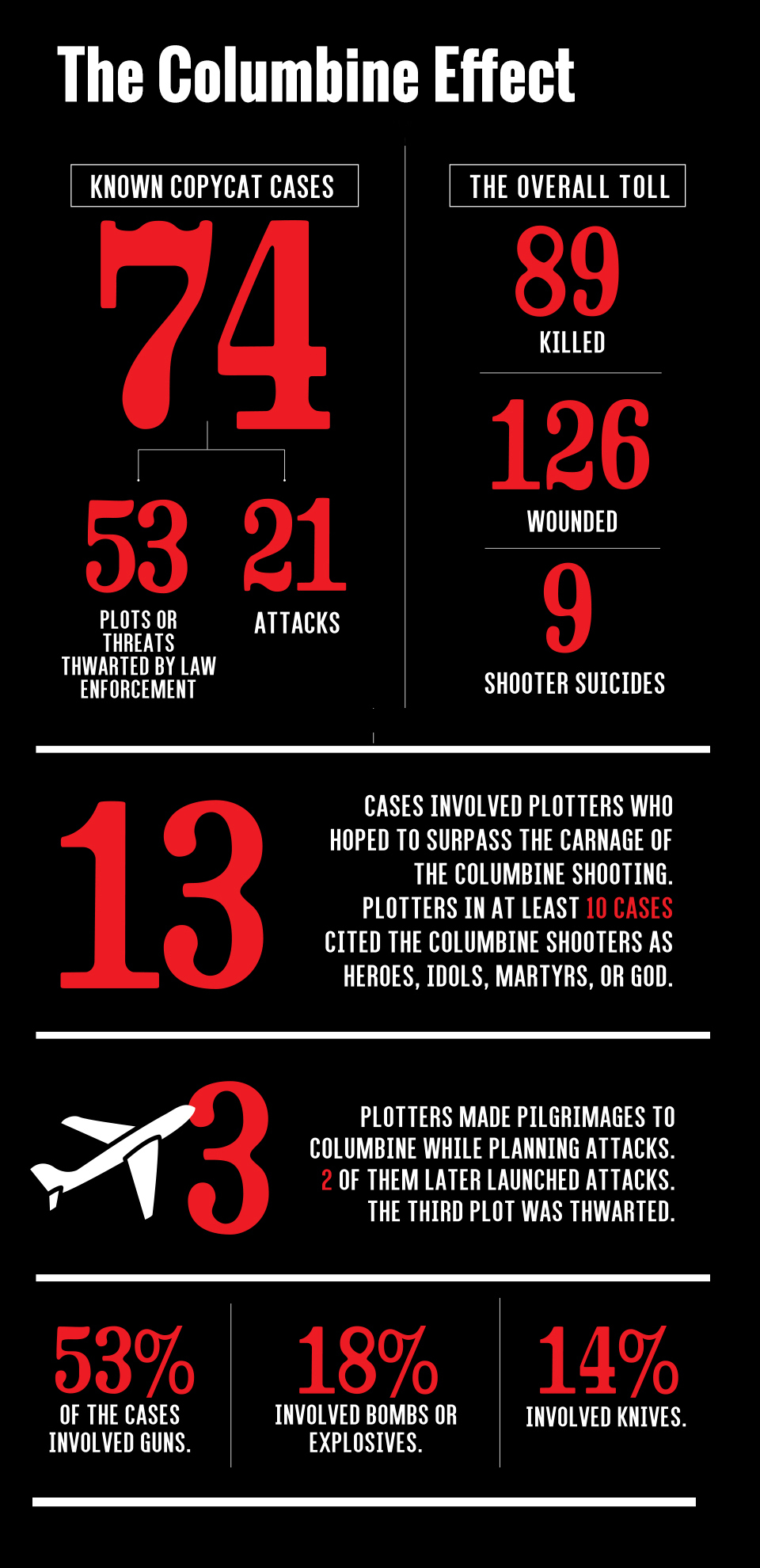

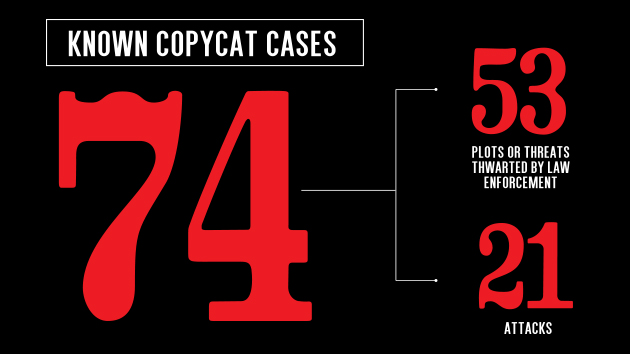

To gauge just how deep the problem goes, Mother Jones examined scores of news reports and public documents and interviewed multiple law enforcement officials. We analyzed 74 plots and attacks across 30 states whose suspects and perpetrators claimed to have been inspired by the Columbine massacre. Law enforcement stopped 53 of these plots before anyone was harmed. Twenty-one plots evolved into attacks, with a total of 89 victims killed, 126 injured, and 9 perpetrators committing suicide.

The data reveals some disturbing patterns. In at least 14 cases, the suspects aimed to attack on the anniversary of Columbine. (Twelve of these plots were thwarted; two attacks ultimately took place on different dates.) Individuals in 13 cases indicated their goal was to outdo the Columbine body count. And in at least 10 cases the suspects referred to Harris and Klebold as heroes, idols, martyrs, or God.

At least three suspects made pilgrimages to Columbine High School—fulfilling the kind of “pseudocommando” mission that researchers have found mass shooters to be obsessed with. Two of them carried out rampages when they returned home—one at a college in Washington state and the other at a high school in North Carolina, using guns he’d decorated with pictures of the Columbine shooters. In another case, a 16-year-old from Utah flew to Denver without his parents’ knowledge, hired a driver to take him to Columbine, and met with the principal under the auspices that he was writing an article for his school newspaper. He was trying to elicit information on lasting trauma, according to a law enforcement official familiar with the case. “All he wanted to know about was what the students and staff felt like—how long it took them to recover and if they still thought about it,” the official says. The teen was arrested back home for plotting with a fellow student to bomb his own high school.

These publicly documented cases are just the beginning. “There are many more who have come to our community and have been thwarted,” says John McDonald, the director of security for Colorado’s Jefferson County school district, where Columbine High School is located. “They want to see where it happened, want to feel it, want to walk the halls. They try to take souvenirs.” Some aspiring copycats have even come from overseas, says McDonald. “The problem is always on our radar.”

Gene Deisinger, a threat assessment pioneer who led Virginia Tech’s police force from 2009 to 2014, explains that the copycat effect also plays out at sites like Virginia Tech and Fort Hood. “Lots of the places that have experienced high-profile acts of mass violence over the last decade or more face ongoing threats from outsiders who identify with the perpetrators, the acts, or the places,” he says.

Major attacks motivate copycats in other ways. In April 2009, Jiverly Wong blocked the back exit of the building in upstate New York where he’d taken English classes and then used guns similar to those of the Virginia Tech shooter to kill 14 people and wound four others before shooting himself. “There was evidence that he had studied the attack at Virginia Tech,” a federal law enforcement official told me, “looking at the chaining of the doors there that had prevented both entry and exit.”

It’s not just Americans who emulate the killers of Columbine or Virginia Tech. Shooters inspired by these events have struck in Brazil, Canada, and Europe—particularly in Germany, where nine school shootings occurred in the decade after Columbine. At least three German shooters drew inspiration from Harris and Klebold, including an 18-year-old who referred to them as God and attacked his former school wearing a long black coat and wielding two sawed-off rifles, a handgun, and more than 10 homemade bombs.

When I asked threat assessment experts what might explain the recent rise in gun rampages, I heard the same two words over and over: social media. Although there is no definitive research yet, widespread anecdotal evidence suggests that the speed at which social media bombards us with memes and images exacerbates the copycat effect. As Meloy and his colleagues noted earlier this year in the journal Behavioral Sciences and the Law, “Cultural scripts are now spread globally…within seconds.”

In late August, this phenomenon reached its logical next step when a disgruntled former TV reporter gunned down two former colleagues during a live broadcast in Virginia while filming the scene on a camera. As he fled, he posted the footage on Twitter and Facebook. The first “social media murder” went viral in less than 30 minutes, raising the grim prospect that others will aim for similar feats—knowing that the news media will put them in the spotlight and help publicize their grisly images. (The 26-year-old who would go on a rampage at Umpqua Community College in Oregon five weeks later reportedly commented online about the Virginia shooting, “Seems the more people you kill, the more you’re in the limelight.”)

But just as digital media has created platforms for dangerous people seeking a blaze of notoriety, it has also become a valuable tool for identifying them. “We’re now seeing that shooters are announcing more frequently via social media just prior to attacking,” Simons says, noting that potential killers can otherwise be conspicuously withdrawn. “When people express violent ideation, what we’re looking for is: Who are they talking to? Who’s listening?” These days, he adds, “it’s possible they’re living more vividly online than in the physical world.”

Erik Ayala could barely sleep. He hadn’t worked for months. He hardly ever talked to his two high school buddies anymore, even Mike, with whom he now shared an apartment in Portland. In the three years since he’d moved there in 2006, he’d struggled to hold down a job or find a girlfriend. Now 24 years old, he was no longer in touch with the teams who had watched over him in his hometown for nearly five years. He had become increasingly withdrawn and often holed up in his bedroom playing Resistance: Fall of Man and other first-person shooter games.

On the morning of January 24, 2009, Ayala scribbled a note apologizing to his family and bequeathing his PlayStation 3, his car, and what little remained in his bank account to Mike. “I’m sorry to put all this on you buddy,” he wrote. “I know it’s not much consolation but as my friend and roommate you are entitled to everything that I own. Good luck in this fucked-up world.” Then he grabbed the 9 mm semi-automatic he’d bought two weeks earlier at a pawnshop and headed downtown.

Just before 10:30 p.m., a group of teens waited in line outside the Zone, an all-ages dance club. Ayala didn’t know anyone at the club, but to him it was a hangout for the kinds of kids he despised. In a matter of seconds Ayala fatally shot two teenage girls and wounded seven people, most of them also teenagers. As a security guard moved toward him, Ayala put the barrel under his chin and pulled the trigger one last time.

It was the worst mass shooting in Portland’s history. Experts also cite it as a prime example of both the promise of threat assessment and its limitations. “Ayala ended up acting out his ideas from high school on a similar, if not the same, target population almost a decade later,” Van Dreal says. That may suggest the two Oregon teams prevented Ayala from going on a rampage when he was younger, but it also reflects the daunting challenge of managing a potentially dangerous person over the long haul. Even if a troubled kid can be turned away from violence, how do you ensure he becomes a well-adjusted adult? What happens when he moves beyond the reach of those who have helped him? When is a case really over?

Others have fallen through the cracks, including James Holmes, who underwent threat assessment and psychiatric care at the University of Colorado-Denver before he dropped out, cut ties with the school, and carried out the movie theater massacre in Aurora. Jared Loughner, who shot Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and 18 others in Tucson, Arizona, in 2011, had been booted out of Pima Community College after its threat assessment team looked at his disruptive behavior. Many mental health professionals still lack the training to evaluate potentially deadly people, says Deisinger, who is a psychologist as well as a cop. And they may be resistant to threat assessment’s tactics and urgency.

“There’s nothing more frustrating than hearing people say there’s no way to stop these mass shootings from occurring,” says Russell Palarea, a forensic psychologist and veteran of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service who now consults for private corporations. Like many in his field, Palarea believes the key is helping more people understand what threat assessment is and how it works—similar to the “see something, say something” campaign meant to help foil terrorist attacks. “The methodology is in place,” he says. “We just need to train the public, law enforcement, prosecutors, hospital clinicians, and other professionals on their roles in helping to manage the threats.”

The science behind threat assessment is still young, but it is attracting growing interest; last year the American Psychological Association launched the Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. The ranks of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals are rising, and since Sandy Hook, more corporate leaders have taken an interest in the strategy. Three states—Virginia, Illinois, and Connecticut—now mandate threat assessment teams in their public colleges and universities. Virginia was the first to do so (after the Virginia Tech massacre in 2007) and now also requires them in all K-12 public schools. (Read more about its model here.)

But should a huge investment in threat assessment really be our only serious effort to stop mass shootings? Australia, another frontier culture with a deep attachment to guns, endured a slew of mass shootings starting in the 1970s. After a disturbed young man killed 35 people and wounded 18 others in 1996, the country invested heavily in gun buybacks and enacted stricter gun laws. Suicides and murders with guns declined dramatically, and Australia has had only one public mass shooting in the two decades since.

Possession of a firearm, of course, is not a meaningful predictor of targeted violence. But at the conference in Disneyland, virtually everyone I spoke with agreed that guns make these crimes a lot easier to commit—and a lot more lethal. “There are so many firearms out there, you just assume everybody has one,” Scalora says. “It’s safer to assume that than the opposite.” The presence of more than 300 million guns in the United States—and the lack of political will to regulate their sale or use more effectively—is a stark reality with which threat assessment experts must contend, and why many believe their approach may be the best hope for combating what has become a painfully normal American problem.

In a sense, threat assessment is an improvisational solution of last resort: If we can’t muster the courage or consensus to change our underlying policies on firearms or mental health care, at least we can assemble teams of skilled people in our communities and try to stop this awful menace, case by case.

Kyle Alexander remembers how he and Erik Ayala met as freshmen in the high school marching band: They were both introverts who loved video games and commiserated about being misfits. Hours before Ayala carried out his attack in Portland, his roommate, Mike, called Alexander, who was living in Seattle. “He’d found the note and he sounded very frantic,” Alexander recalls. “He wanted to see if I knew Erik’s whereabouts.” Alexander was worried but didn’t know what he could do from so far away. Mike was also at a loss. “At the time we thought Erik was just going through another bad cycle of depression,” Alexander says. “We never saw it coming.”

Only recently did Alexander learn the full details of Ayala’s case, including that he had once been on Ayala’s hit list. “It was surprising, and scary to think about,” he says. “Erik would go through very dark moods, but given the special relationship we had I was often able to help him turn things around.” Alexander wishes he’d stayed closer with Ayala after high school. “The social relationship piece of it is big,” he says. “I think it could’ve made a difference in his life.”

Alexander is now 32 years old and lives in Salem, Oregon, where he works as a school psychologist. He is trained in threat assessment and works with school-based teams in his district. His passion is helping at-risk kids.