Frustrated by the two-party system? Polling shows you’re not alone, with more Americans than ever supporting the idea of a third party. But the winner of November’s presidential election will be either Biden or Trump, and voters weighing other candidates need to consider if a protest vote to end the duopoly might instead help end our democracy. In the May+June 2024 issue, we examine the past and present of third-party outsiders, and how they could upend this year’s race. You can read all the pieces here.

The war for control of the Libertarian Party of New Hampshire began to escalate in the spring of 2021, when Jeremy Kauffman got the keys to the Twitter account. Kauffman, a tech entrepreneur, had arrived in the state a few years earlier as part of the Free State Project, which proposed to transform New Hampshire by convincing liberty-minded activists to move there en masse. The state was a small-l libertarian success story. It had legalized raw milk, slashed budgets, and elected dozens of Free Staters to the legislature—including the House majority leader. But the state and national Libertarian parties, Kauffman felt, were too passive and too left-wing. They were trying to fit in, instead of trying to stand out.

He and his allies made short work of that. In the months that followed, the LPNH account made national headlines with a run of deliberately provocative statements. The party tweeted that “John McCain’s brain tumor saved more lives than Anthony Fauci.” It called for child labor to be legalized and advocated repealing the Civil Rights Act to fight “wokeness.”

State party chair Jilletta Jarvis watched this shift with alarm. A group of right-wing activists was attempting a “hostile take-over,” she announced. Jarvis pointed her finger at a new and rapidly growing caucus within the state and national parties that was named for Ludwig von Mises, a 20th century Austrian free-market economist who was one of the intellectual forefathers of libertarianism and who is particularly revered by followers of the former presidential candidate Ron Paul. “Their strategy is, frankly, designed to discredit the Libertarian Party in the state and in our nation,” Jarvis warned.

So she and a group of like-minded party members staged a counterrevolution. They seized the Twitter account from Kauffman and his allies and created a new legal entity to house the party’s assets. Then Jarvis made one more announcement: “Out of respect for all of those who have been angered, threatened, or insulted by the Libertarian Party of New Hampshire,” the party’s social media accounts would be going on a brief hiatus.

Being the third-largest party in a duopoly can sometimes seem like a dubious distinction, like being the second-deadliest maritime disaster involving an iceberg. The Libertarians are big enough to be ubiquitous, but rarely substantial enough to stand out. For decades their nominees have oscillated between people you’ve never heard of and those you vaguely remember. The Libertarian Party is America’s weakest strong brand.

In 2016, the Libertarians had their best-ever presidential election showing by a factor of three. Dissatisfied by two unpopular major-party nominees, nearly 4.5 million people voted for the strange-but-plausible pairing of former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson and ex–Massachusetts Gov. Bill Weld. Running on a promise of “socially liberal, fiscally conservative” governance, they exceeded the margin of victory in 11 states and raised more than $11 million. It was the best performance by a third party in a presidential election since Ross Perot.

Gary Johnson greets supporters at his election-night party in 2016 in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Juan Labreche/AP

Then it all fell apart. Under the auspices of expanding the tent, some within the LP—and a fair number outside of it—began clamoring for a different kind of party: more aggressive, more offensive, and more right-wing. They weren’t interested in third-place showings; it wasn’t entirely clear if they were interested in competing at all. What’s followed has been more than seven years of spectacularly messy infighting. New Hampshire was only one front of many. Across the country the Libertarian Party has been plagued by breakaway factions, leaked chatrooms and conspiracy theories, and bitter struggles over bank accounts and social media handles.

The current electoral climate is once again tailor-made for a Libertarian party crasher. From the militarized border to attacks on bodily autonomy, state power and individual liberty are at the foreground of the national debate. Faced with an unpopular incumbent and a challenger charged with 88 felonies, 63 percent of Americans say they’re ready for a third-party alternative. But the largest one bears little resemblance to the party that attracted so many disaffected voters in 2016. Instead, it’s mired in a tussle that’s all too familiar, not just between its left and right flanks, but over the purpose of the party itself. The rise of Trump didn’t just break the Republican Party. It reignited an identity crisis within the LP that has been smoldering since its creation.

The Libertarian Party was formed in the 1970s amid backlashes to imperial Republican governance and the Democratic Great Society. Members skirmished over the organization’s purpose from the outset. “There were arguments over ‘Is the point of the Libertarian Party to have a platform to say what you think is true, or is it to actually try to win elections and put libertarians in office?’ and I don’t know that that was ever really settled,” says David Boaz, distinguished senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, who has seen the movement evolve from its inception.

Those debates often manifested as fights over candidates. In 1980, some Libertarians accused their nominee, attorney Ed Clark, of watering down their message to win votes. His sin? Defining libertarianism in an interview as simply “low-tax liberalism.” Clark, whose running mate was the oil magnate David Koch (brother Charles co-founded Cato and bankrolled much of the early libertarian movement), won what was then a record number of votes, but the campaign also sparked infighting that led to an exodus from the party. Four years later, the Kochs backed a member of the Council on Foreign Relations for the nomination. When the party chose someone else, it was their turn to walk.

“When there have been real serious schisms or fights within the party they have been within roughly the same lines as now,” says Brian Doherty, a senior editor at the libertarian magazine Reason, whose book Radicals for Capitalism chronicled the movement’s rise. “This is not how the Mises Caucus people would put it, but an objective outside observer might say it’s a war between normie pragmatists—that would be the Gary Johnson side—and, you know, radical weirdos.”

In 1988, the party’s old guard threw their support behind Ron Paul, hoping that a former Republican congressman might make some noise nationally. Paul, who paid for his lifetime party membership with a gold coin, happened to be both a normie and a weirdo. Compared to his rival, former American Indian Movement leader Russell Means, he was a Beltway insider. But Paul’s cultural conservatism and paranoid style were an imperfect fit. He was not a member of the Council on Foreign Relations; he spread conspiracies about the Council on Foreign Relations.

After a disappointing showing, Paul rejoined the GOP and the Libertarian Party fractured again. Two of his most vocal allies, Lew Rockwell (a former Paul chief of staff) and Murray Rothbard (a Cato co-founder who fell out with Charles Koch), retreated to a nonprofit Rockwell had set up called the Mises Institute, where they advocated for something called “Paleolibertarianism”—a fusion of libertarian economics and proto-MAGA politics. In a 1992 essay lamenting former Klan leader David Duke’s defeat in the Louisiana governor’s race, Rothbard outlined a platform of “right-wing populism” that included eliminating the welfare state, abolishing the Federal Reserve, and repealing civil rights laws. The seventh bullet point was “America first.” Still stewing from their LP experience, Rothbard and Rockwell argued that libertarians should abandon their woke cultural liberalism; a racist newsletter published by Paul, which listed Rockwell as an editor, had a recurring feature documenting crimes committed by Black people. It was called “PC Watch.”

The Paleo crowd was in the wilderness for a while. Paul’s bids for the Republican presidential nomination in 2008 and 2012 changed that, introducing a new generation to his own strain of right-leaning libertarianism. He brought all sorts of political outsiders into the GOP, and exposed them to ideas, like abolishing the Fed or opposing the war on terror, that no one else in the party much talked about. When Paul supporters found their progress blocked in the GOP, they inevitably took a look at the Libertarian Party. In the decade following Paul’s 2008 run, membership grew 92 percent. Paul was no Paleo, but his positions also placed him at odds with many traditional Libertarian tenets. He campaigned on ending birthright citizenship; the LP supported “unrestricted movement” of people and capital across national borders. He was a pro-life OB-GYN; the party believed the government should be “kept out of the matter” of abortion. He opposed LGBTQ equality; the LP had supported gay marriage since its inception.

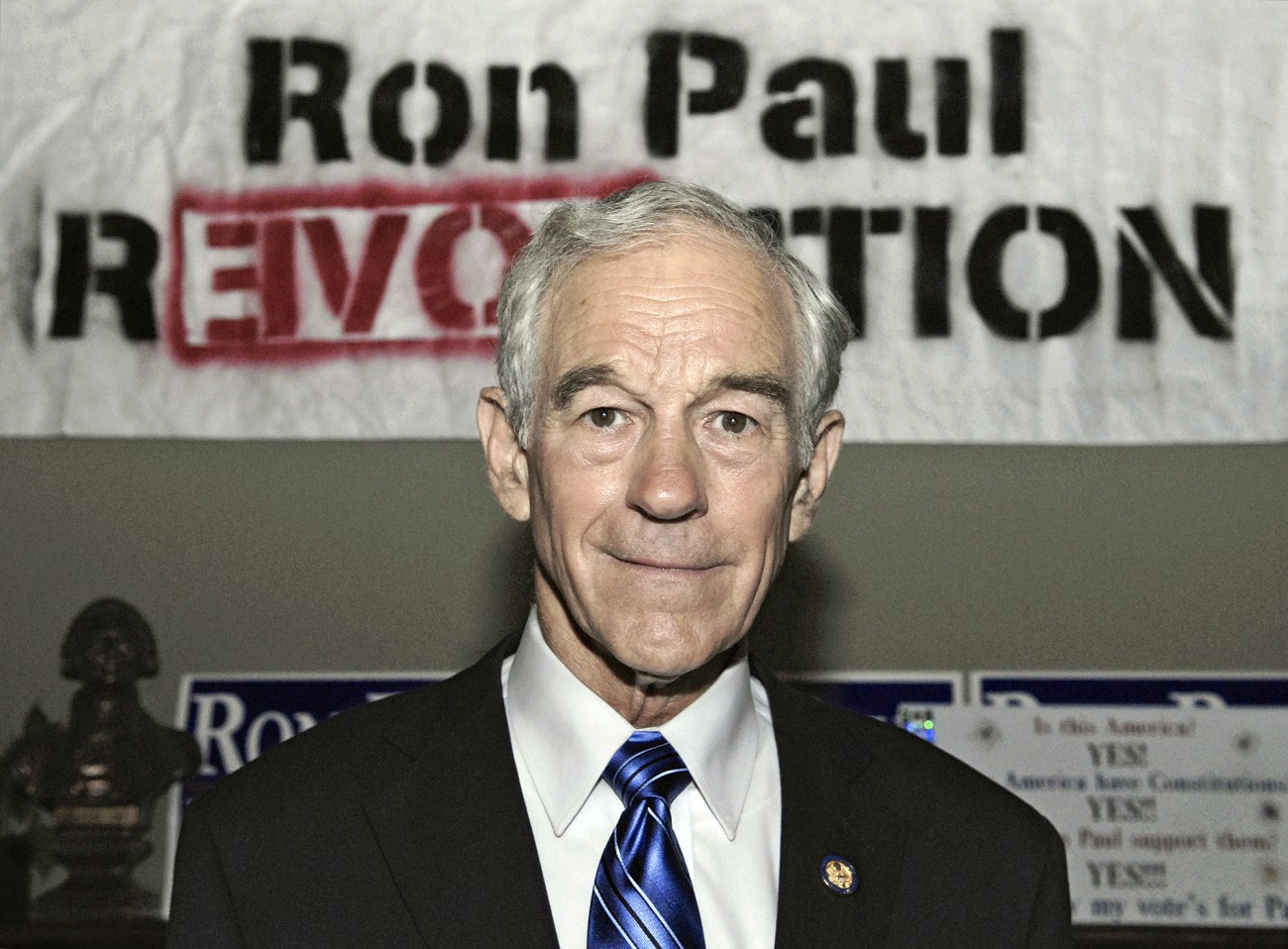

Ron Paul following a GOP debate in 2007

Chris Fitzgerald/Candidate Photos/Newscom/Zuma

There was one more notable distinction: Paul wanted a revolution. The LP, by contrast, had developed a reputation in some circles as “a rest home for Republicans who like pot,” Doherty notes. Pragmatists believed that strong performances by reputable figureheads put pressure on the major parties to be more receptive to their views, boosted ballot access and fundraising, and supported candidates at the state and local level. (The party touted nearly 200 elected officials by 2018.) In 2012, four years after ex–Georgia Rep. Bob Barr won a half-million votes, Johnson became the first Libertarian Party presidential candidate to crack a million.

When Johnson ran again in 2016, the conditions seemed ideal for a third party to attain the mythical 5 percent—the threshold at which a party qualifies for federal matching funds. As his running mate, Johnson chose Weld, a WASP’s WASP who proclaimed that he wanted the government “out of your pocketbook and out of your bedroom.” It was hard to imagine either of them blowing up the system.

Not unlike what played out during the 1980 campaign, the self-appointed “libertarian wing of the Libertarian Party”—the sort of people who call Cato “Stato” and Reason “tReason”—blanched at the normies in their midst, and their sanitized message. There’s a video from the 2016 Libertarian Party convention that captures the challenges of rallying a party of individualists. A moderator asks the presidential candidates whether the government should require driver’s licenses. Austin Petersen, a former FreedomWorks staffer, says, “Hell no.” “What’s next, requiring a license to make toast in your own damn toaster?” says Darryl Perry, an anarchist whose campaign conducted all its transactions in cryptocurrency and precious metals. Then it is Johnson’s turn.

“You know, I’d like to see some competency exhibited by people before they drive,” he says, holding up his hands in mock surrender.

The crowd boos.

On paper, Johnson’s performance was a high-water mark, even if it fell short of the 5 percent target. But Weld, a former law-and-order champion, was a bridge too far for some. Late in the race, he told voters in swing states that Hillary Clinton should be their second choice. Some in the party believed the LP had sold out again.

The Trump era had a way of surfacing submerged tensions. While pragmatists saw an opportunity for the LP to build on their momentum by courting disaffected partisans, some Paul disciples were tugging in a more right-wing direction. In 2017, the then-head of the Mises Institute (yet another former Paul chief of staff) gave a speech stating that libertarians risked “irrelevance” unless they acknowledge that “blood and soil and God and nation still matter to people.” The phrase “blood and soil,” of course, matters to a very specific group of people; a few weeks later, white nationalist Richard Spencer’s mob chanted the Nazi slogan in Charlottesville.

The Unite the Right rally offered a glimpse of libertarianism’s dark side. Multiple participants in the event had run for office as Libertarians, including Chris Cantwell, an organizer who claimed Rothbard as an influence. Spencer himself admired Paul and had previously spoken at an immigration conference organized by a Mises Institute scholar. The so-called “alt-right” was littered with people for whom libertarianism was less an ethos of non-aggression than a placeholder before admitting they were just white nationalists.

In the aftermath of the rally, the LP’s executive director said there was “no room for racists and bigots in the Libertarian Party.” Nicholas Sarwark, the party’s chairman between 2014 and 2020, went further; the Mises Institute, he tweeted, was “the preferred choice of actual Nazis.” It was a breaking point. Many Paul supporters already considered the pragmatists too woke. Targeting Paul’s favorite think tank only proved their suspicions. That same day, a 28-year-old from the Philadelphia suburbs named Michael Heise started a Facebook group called the Libertarian Party Mises Caucus. By the next morning the group had 600 members. “We’re bringing libertarianism back,” it announced over a meme of Paul walking away from an explosion.

Heise was characteristic of the sort of young men drawn to Paul’s revolution. A fan of Alex Jones and Infowars as a teenager, he became active in Paul’s campaign and contributed to the movement by filming encounters with police and leading anti-Fed protests while holding a bullhorn with a sticker that said “9/11 was an inside job.” After Paul left the political stage, Heise washed his hands of the GOP, but he also thought the LP was a “joke” and found Johnson uninspiring. He watched the Paul revolution fragment—some followers went MAGA; others just dropped out.

Michael Heise

ReasonTV/Wikimedia

“If we ever did get that back under the guise of an organization as opposed to a single campaign, it never has to die,” he explained on a podcast in 2017, not long after forming the Mises Caucus. “It can just keep going and going.”

Heise disavowed the tiki torchers of Charlottesville—Cantwell, he said, had “gone nuts”—and the Mises Caucus dismissed Trump as a “tyrant.” Later that year, the caucus declared that “Anyone accusing us of being alt-right either knows nothing about us, or is intentionally spreading lies,” and boasted that it had “kicked more alt-right types from our FB group than any other.”

But the alt-right and the Mises Caucus shared some common influences. The Mises Caucus adored Rothbard and pledged its opposition to not just “political opportunists” but “identity hustlers.” Another hero was a Mises Institute fellow named Hans-Hermann Hoppe, who advocated for major restrictions on non-white immigration. He said in 2017, “Any promising libertarian strategy must, very much as the Alt-Right has recognized, first and foremost be tailored and addressed to…the most severely victimized people,” which he identified as “White married Christian couples with children.” (Mises the economist, for what it’s worth, was a Jewish refugee from Nazism who believed that “every person [has] the right to live wherever he wants.”)

The insurgents felt the party had turned a cold shoulder to Paul and the sorts of outsiders he had welcomed—homeschoolers, “medical freedom” activists, and others on conservatism’s fringe. Angela McArdle, a Los Angeles libertarian who would later run for party chair, argued that the party should consider targeting people who “are into intellectual dark-web stuff.” Everyone seemed to have a podcast. People attracted to this movement weren’t Trump supporters per se, although some were—future Stop the Steal ringleader Patrick Byrne gave $5,000 in seed money to the Mises Caucus, and a former member of its advisory board ran a group called Libertarians for Trump.

The slate of Mises Caucus members running for key party leadership positions initially struggled to break through, but their anger was having an effect. Weld, who had planned on seeking the 2020 nomination, thought better of it. So did another ex-Republican (and ex-Democrat), Lincoln Chafee. Michigan Rep. Justin Amash, who quit the GOP over its descent into “nationalism,” started and then folded an exploratory committee. Amash, Heise warned in an email to members, “reeks of the same thing [that’s] been going on with this party for years now: a longtime duopoly member joining the party without putting any type of investment into it.” The rest home was closed.

The party eventually settled on Clemson University psychology lecturer Jo Jorgensen, who made national headlines for being bitten by a bat. Jorgensen—whose 1.1 million votes were a fraction of Johnson and Weld’s 2016 total but still the party’s third-highest tally ever—also managed to offend the Mises crowd. They believed she’d gone woke, pointing to her statement after the murder of George Floyd that “we must be actively anti-racist.” Worse still, they felt she’d been too timid during Covid, embracing social distancing and masks even as she criticized lockdowns.

In the run-up to the 2022 Libertarian Party convention in Reno, the Mises Caucus raised nearly half a million dollars and planned for what it called “The Takeover.” Supporters began to wrest control of local and state parties. That summer the caucus’ slate routed their opponents. McArdle, a paralegal who led protests against vaccine mandates, was the new chair. The convention removed from the platform a long-standing plank condemning bigotry as “irrational and repugnant,” on the grounds that it wasn’t the LP’s job to police speech. The assertion “that government should be kept out of the matter” of abortion was jettisoned too. And amid right-wing rumblings about a “National Divorce”—the idea that the United States should resolve its divisive policy fights by splitting into smaller countries—the party added a plank recognizing “the right to political self-determination, including secession.” The new LP announced that Paul supporters were welcome “with open arms” and name-checked his newsletter collaborator, Rockwell. Dissenters quit the party in droves.

“If someone is in the pool and someone poops in the pool,” says John Hudak, a libertarian who split with the Mises faction, “a lot of people are just going to get out.”

After Reno, the new LP got to work. Instead of an ex-Republican, some Mises Caucus members floated their own 2024 presidential candidate—Dave Smith, a comedian and frequent guest on Joe Rogan’s podcast. Although he did not identify as alt-right, Smith was comfortable in their company; he had invited both Cantwell and the white supremacist Nick Fuentes onto his own show.

This new LP was different not just in substance and strategy, but in style. Kauffman’s activities in New Hampshire, where he and a few others were continuing to attract attention for, among other things, calling the Uyghur genocide “fake” and offering to send a Black Democrat to Africa, offered the extreme version of this shock-and-awe approach.

“Every time people see ‘New Hampshire’ and ‘libertarian,’ that’s good,” Kauffman told me. “People say, ‘New Hampshire is full of crazy, insane libertarians’—that’s good. Everything that reinforces that marketing perception that New Hampshire is the libertarian homeland, New Hampshire is full of libertarian crazies—that is everything that I want to happen.”

Indeed, that’s more or less how things played out: Johnson and Amash condemned the attacks on McCain; the state’s Republican governor said the tweets “should pretty much be the end of the Libertarian Party in New Hampshire.” State party chair Jilletta Jarvis and her allies briefly wrested control of the Twitter feed, but their intervention was short-lived. Even the national Mises Caucus leadership, recognizing that endless news coverage of one state party’s tasteless posts was not a great look, eventually urged the New Hampshire crew to tone it down, to no effect. While they shared a common frustration—woke left-libertarians—people like Kauffman weren’t interested in any national strategy. Starting a revolution, the Mises Caucus learned, was a lot easier than managing one.

A different sort of chaos was unfolding across the country as right-leaning factions clashed with more moderate ones. In Massachusetts, party leaders fought back and eventually started a new party after the state Mises affiliate called them “rootless cosmopolitans.” In Delaware, Idaho, Pennsylvania, and Michigan, Mises opponents either attempted to seize control of their parties or to form new organizations. The Virginia and New Mexico affiliates cut ties with the national party altogether. National Divorce was coming for the party that now officially advocated for it.

While the insurgents had railed against high-profile candidates who diluted the brand, the new management faced a series of campaign-trail embarrassments that inflamed suspicions of a not-so-secret MAGA bias. Its Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate was a sex offender who was Rudy Giuliani’s star witness at the notorious Four Seasons Total Landscaping press conference following Trump’s defeat. Arizona’s libertarian Senate nominee dropped out in the final weeks to endorse the avowedly ex-libertarian Blake Masters. Last year, Jacob Chansley, a.k.a. the QAnon Shaman, announced he was running for Congress as a Libertarian. The national party, which has mocked the idea that January 6 was an attack on democracy, welcomed him with open arms.

The problems weren’t limited to schisms and candidates. A 2023 analysis from another LP group, the Classical Liberal Caucus, found that fundraising, adjusted for inflation, was the worst it had been in 30 years. One major donor announced he was removing the LP as the beneficiary of a $650,000 trust. Sustaining memberships had fallen, too. Around that same time, Hudak posted a trove of documents from a disgruntled Mises Caucus member detailing rampant infighting and low morale among party members.

“The Takeover is turning into a disaster,” McArdle wrote in one May 2023 memo. And there was more bad news to come. Mises members had counted on Smith to enter the presidential race in 2024, using his podcast audience to give the party a dynamic anti-Johnson.

“Surprise! Dave Smith isn’t running for President. He backed out and people are going to be really upset,” McArdle wrote. “No one is coming to save us.”

They still aren’t. Heise, the Mises Caucus founder, predicted in October the presidential race would be a “struggle” for the party just to tread water. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was courting Libertarian voters for his independent campaign, and McArdle even suggested that an alliance between the two could be mutually beneficial. But the Mises Caucus rejected the idea; instead, the group was supporting Michael Rectenwald, a former New York University professor who backed Trump twice and has published three books in five years about cancel culture. “Open borders,” Rectenwald said at a candidate forum in December, “plays into the globalist objective” to “erode the entire culture base of the United States.” Plenty of voters share those views. They already have a candidate.

When we spoke in February, McArdle sounded more optimistic about the party’s future. The fundraising and marketing strategies were now in sync. The battles for control of state parties, she said, were proof that the revolution was working.

“I underestimated the hatred that people would have for me personally, and the interest that they would have in destroying their own organization,” McArdle said. “I think a lot of those people were not well grounded in reality and didn’t have a lot of balance in their lives and it was extremely difficult for them and they acted in bad faith. It’s like Solomon’s baby—they’d rather split it down the middle.”

But the fight over the LP is not just about tone or policy or friendships. Hovering over all of it is a question about the utility of third parties themselves. It is a variation of the debate that’s roiled the LP since the days of Clark and Koch: What are they actually trying to do here?

In a statement last year saying he would not seek the party’s presidential nomination (he is instead running for Senate as a Republican), Amash pointed to the LP’s weakened prospects under its current leadership. “If anything, my policy views align more closely with those who describe themselves as right-libertarians,” he acknowledged—he was, himself, an acolyte of Paul. But “we just have a different philosophy about the role of parties.” People who wanted to push a specific ideology, he said, should do so through activism. The point of the LP was to organize libertarian-minded people to win elections. It sounds simple when you put it like that. For the LP, though, it never has been.

“I do think one of the problems is that some people called themselves libertarian when in fact what they really were was angry, alienated, contrarian, liking to shock people,” says Boaz, the Cato eminence, who delivered a speech this year calling out “blood and soil” rhetoric as anti-libertarian.

The Libertarians are hardly the largest party to turn on democracy in the Trump era. But the LP’s recent endorsement of a “National Divorce” is not just a radical turn, but a reflection of its own fractious nature. If schisms are endemic, perhaps the best course is to embrace them. Can’t agree on abortion rights? National Divorce. Can’t agree on gun control? National Divorce. There’s no problem that more factionalism can’t solve—not even the plight of the perennial third wheel. “There is potential for us to split into many different governments,” McArdle wrote last year in Reason, “maybe even a libertarian state.”

On second thought, better make that two.

In May, Libertarian Party delegates will meet in DC to choose a presidential candidate, and maybe even a new direction. But the convention slogan, at least, is one policy proposal they’ve already delivered on: “Become Ungovernable.”