When he ran for president in 2004, Democrats were counting on Sen. John Kerry’s military service to define him as a strong leader after 2001’s terrorist attack and George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq. The decorated Vietnam War veteran headed into the party’s convention with a 3-to-6-point lead over Bush, who had dodged serving in the war by enlisting in Texas’ Air National Guard. But just a week after Democrats officially nominated him, Kerry found himself, and his military service, under attack from unexpected quarters: a group of veterans who, like him, had served on swift boats in Vietnam.

A brutal and deceptive series of ads featured the veterans accusing Kerry of lying about his military record and the injuries that had earned him medals. His lead soon evaporated. The campaign never recovered, and “swift boating” entered the lexicon as shorthand for a dishonest political smear. The man largely responsible for the ads was a Virginia political consultant named Chris LaCivita. He now works for Donald Trump as a senior advisor and co-campaign manager. And if history is any guide, Democrats should be very, very worried.

“Chris is one of the most effective campaign operatives I have ever known,” says his friend Mo Elleithee, a former Democratic operative who directs Georgetown University’s Institute of Politics and Public Service. “He is a brass knuckle brawler who understands what moves voters better than almost any operative I have ever known on either side of the aisle. And he pulls no punches.”

When Trump announced a presidential run in 2015, the reality TV star’s campaign was widely considered a joke; the Huffington Post made a show of covering it in its entertainment section. The effort was frequently a disorganized mess, run by a revolving cast of characters, several of whom would be convicted (and ultimately pardoned) for crimes related to the special counsel’s investigation into the campaign’s links to Russian efforts to influence the election. Their victory over Hillary Clinton seemed to come as a surprise even to Trump.

But 2024 is shaping up to be very different. “Donald Trump is a movement,” explains former Rep. Tom Davis (R-Va.). “That’s how he won this thing originally. But it was kind of rag tag. This time he has everything going for him. He has a huge, disciplined ground operation, a coordinated message operation.” A lot of that, Davis suspects, can be credited to LaCivita, whom he’s known for decades from Virginia politics. “He’s the kind of guy that Trump listens to outside of the family and can take control.”

Like most aspiring strongmen, Trump has a thing for military people, which makes LaCivita a perfect fit. The operative enlisted in the Marines after graduating from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1991, and soon deployed to the Gulf War, where he was wounded by shrapnel in the face.

Today he’s known for running campaigns like a take-no-prisoners military operation, looking around corners and war gaming outcomes. In 2014, for instance, when Republicans were on the verge of losing control of the Senate, Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) dispatched LaCivita to save the floundering campaign of Kansas Senator Pat Roberts, who no longer had a home in the state. When LaCivita unleashed a harsh negative campaign targeting Roberts’ opponent, the senator’s wife and daughter complained, according to the Washington Post, and asked LaCivita to dial back. He refused. Roberts ultimately won the race by more than 10 points, preserving McConnell’s GOP’s majority.

LaCivita got his start in politics helping future Virginia Senator George Allen get elected to Congress. He quickly earned a reputation for loyalty to his candidate. In 1992, when Allen ran for governor, state politicos were set to gather at the Virginia shad planking, an annual ritual where candidates, reporters, and partisans glad-hand and eat smoked fish. The night before, LaCivita stayed up with a friend blanketing the area with Allen signs.

At 4 am, LaCivita realized they’d missed a spot: an island in a nearby millpond. He grabbed some signs, jumped in and swam out. The story is now the stuff of legend, with varying accounts putting the pond’s temperature at either 45 or 50 degrees; it was one sign, or maybe 10. LaCivita jokes that he pulled the stunt “with enemy bullets raining down and fire and there was a dragon.” In reality, he says, “It was about 100 yards. The water was cold. I did not jump in fully clothed.”

“I don’t do stupid shit like that anymore,” he adds.

News stories going back to that time describe LaCivita, now 57, as a “Republican hit-man”—“hyperactive,” “manic,” “renegade”—with a rough-and-tumble approach. He has cultivated this reputation with the media, making himself far more accessible than many MAGA figures. (Indeed, the gregarious conservative talked to me on the record for this story, while just weeks before, the Trump campaign had refused to give me press credentials to cover its Iowa caucus events.)

Take a 2011 interview he did with a reporter from the Richmond Times-Dispatch, conducted over a salad topped with venison LaCivita had killed himself. He recounted pacing around the campaign office during Allen’s 2000 Senate bid “barking orders with my Marine sword, stabbing it into the wall.” When I asked if he still wielded a sword at work, he lamented that “they have these things called human resources now.” Another time, he shot a goose while on the phone with a Washington Post reporter. (“I live in a rural area so I can do that,” he told me, laughing. “I would not last long in suburbia.”)

While Trump’s 2024 campaign is the first time LaCivita has directly worked for the candidate, he’s spent the previous two election cycles helping from the outside. In 2016, he began with Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul’s presidential effort, and when it ended, went to the RNC, where he was put in charge of that year’s convention’s rules committee. In that role, he helped stave off attempts from Never-Trump Republicans, led by one of LaCivita’s former clients, former Virginia attorney general Ken Cuccinelli, to hamper Trump’s path to the nomination.

During the 2020 campaign, he headed up Preserve America, a pro-Trump super-PAC whose $100 million-plus in spending largely came from casino magnate Sheldon Adelson, who died in 2021. LaCivita says he was brought on the current Trump campaign by his longtime friend Tony Fabrizio, Trump’s pollster, who introduced him to Susie Wiles, a veteran operative who’d helped win Florida for Trump in 2016. Wiles was heading up the 2024 campaign and brought LaCivita more directly into Trump’s orbit. The two now work as senior advisors and co-campaign managers.

LaCivita has long been associated with the dark arts of politics, a reputation that that has its roots in 2002, when he served as political director of the National Republican Senatorial Committee for the midterm elections. That year, New Hampshire’s state GOP had hired a telemarketing firm to sabotage a get-out-the-vote phone bank run by Democrats and local firefighters who were arranging rides for voters during a hot Senate race between Republican John Sununu and then-Governor Jeanne Shaheen.

But when the phone bank started getting inundated with hang-up calls, Democrats called the police. While Sununu won the election, and the GOP recaptured the Senate majority, investigators traced the calls to an out-of-state telemarketing firm and brought in the feds. Three people connected with the phone-jamming scheme ended up pleading guilty to federal telephone harassment charges, including the state party’s executive director.

One of LaCivita’s direct reports, NRSC northeast regional director James Tobin, was indicted for hooking up the local party officials with a GOP telemarketing firm willing to jam the phones. Records in his case showed Tobin had made dozens of calls to the White House political office in the period around Election Day. The RNC paid millions of dollars for his legal defense, leading Democrats to raise suspicions the GOP was desperate to make sure he didn’t implicate any other party officials. Tobin refused to cooperate and fought the charges, but a jury found him guilty of conspiracy and aiding and abetting interstate telephone harassment. He was sentenced to 10 months in prison. An appeals court overturned his conviction in 2007, ruling it was unclear whether jamming phones constituted harassment; Tobin did not return a call for comment.

Prosecutors never charged anyone in the White House or other GOP entities outside of New Hampshire with any crimes, but they did include LaCivita’s name as a potential witness in Tobin’s case. He was never called to testify, but lawyers for the New Hampshire Democratic Party did depose him in a civil suit that was settled on the eve of trial without implicating LaCivita or any other GOP higher-up. “I was nothing but a witness” in the suit, LaCivita told me. Despite Tobin’s involvement, he calls the phone-jamming scandal “a stupid, half-brained, cockamamie idea” cooked up by “two local guys in New Hampshire who did not work for me.”

If LaCivita had been only on the periphery of the phone-jamming scandal, two years later, he would be smack in the middle of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth controversy. A group of Vietnam vets who’d had it in for Kerry since his Nixon-era anti-war activism were organizing an attack on the candidate’s military record. “They came to me because I’m a combat veteran myself and I could identify with them,” LaCivita told the Times-Dispatch at the time.

One of the veterans, John O’Neill, had co-authored a book with Jerome Corsi, then a reporter with the conspiracy theory website WorldNet Daily, called Unfit for Command. It laid out their allegations that Kerry had lied about his service captaining swift boats in Vietnam’s rivers. LaCivita helped turn the book into a series of ads, paid for by wealthy Bush supporters.

The spots were so devastating that years later, Kerry shared in an NPR interview that when he first heard one he told staff, “If I heard that ad, I wouldn’t vote for me.” But many of the allegations were contradicted by other witnesses or disproved by Kerry’s service records. Fellow Vietnam War veteran Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) denounced the attack as “dishonest and dishonorable,” and the Bush campaign sought to distance itself from the effort.

Elleithee says that while he respects LaCivita, he “doesn’t love everything he’s done,” and the Swift Boat campaign is the number one example. “I think they crossed a line.” But LaCivita makes no apologies. “We gave a group of veterans the ability to communicate a message,” he says. “I don’t really care what people think. I’d do it again tomorrow.”

The ads “became a template for the modern right,” says Matt Gertz, a senior fellow at the liberal watchdog group Media Matters. “It’s the lightning in the bottle that GOP operatives have been trying to recapture ever since.”

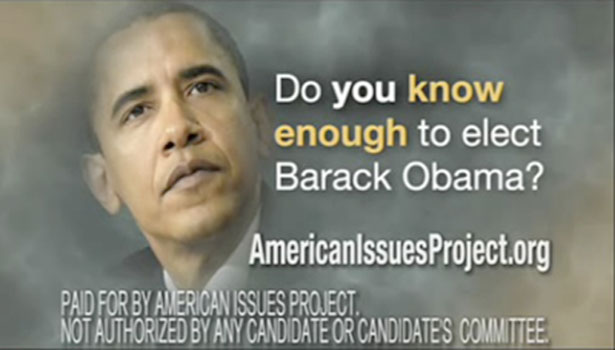

Indeed, Gertz recalls, many of people involved with the Swift Boat vets, including LaCivita, tried a similar approach with Barack Obama in 2008. With funding from the late Harold Simmons, a Dallas businessman who had contributed $2 million to the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, LaCivita co-founded a dark money organization called the American Issues Project. It paid for a series of ads based on another book by Corsi trying to tie Obama to the former ‘60s radical Bill Ayers. “Jerome Corsi, during his press tour for that one, decided to spend most of his time talking about Obama’s birth certificate,” says Gertz. “It all went downhill from there.”

Despite the circles he travels in, LaCivita is known for being fairly transparent with his attacks. “I have found him, ironically, to be highly ethical,” Davis told me. “If he was going to go after you, he’d look you right in the eye.”

Take the case of Rep. Bob Good (R-VA), who in January became the chair of the far-right and generally pro-Trump House Freedom Caucus. Good has pushed the impeachment of President Joe Biden and helped oust former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. But in mid-January, an upstart state senator announced he would challenge Good in a GOP primary. What had Good done wrong? He had endorsed Ron DeSantis over Trump.

Trump has made retribution a centerpiece of his campaign, and Good’s disloyalty didn’t go unnoticed. “Bob Good won’t be electable when we get done with him,” LaCivita said in a text to a local reporter. Virginia politicos who know LaCivita didn’t see the message as posturing. “I’ve never known Chris LaCivita to make an empty threat,” tweeted University of Virginia political science professor Larry Sabato. “Chris won a Purple Heart in the Persian Gulf war. Just sayin’.”

I’ve never known Chris LaCivita to make an empty threat. Sounds like all-out GOP war. Chris won a Purple Heart in the Persian Gulf war. Just sayin’. https://t.co/Vx3yXZyZV2

— Larry Sabato (@LarrySabato) January 17, 2024

In a 2014 interview, LaCivita told the Southern Methodist University’s Center for Presidential History, “My personal philosophy is, I don’t win campaigns. I just keep candidates from losing them. My job is to keep them from making mistakes… I have to keep a bigger picture focus.”

Trump’s mistakes would surely test the skills of even the most seasoned political warrior. The day before I spoke with LaCivita, Trump had insisted on taking the stand in the second defamation case filed by E. Jean Carroll. The judge introduced Trump by instructing jurors that a previous trial had already found that Trump “had inserted his fingers into [Carroll’s] vagina” in a department room dressing room. The jury then hit Trump with an $83 million judgement. How does anyone run a successful campaign where such episodes seem to happen every other week?

And who would really want the job? It hasn’t ended well for others who’ve tried. But when I asked LaCivita whether he had any reservations about working directly for Trump, he said with a hearty laugh that it only “took me about 5 minutes” to agree to come on. “It’s a great opportunity that President Trump gave me.” It’s the kind of response that would please a former president who puts a premium on loyalty among his close advisors. So was LaCivita’s answer when I asked whether he believed Trump had won the last election. “The Democrats rigged the election in 2020,” he replied, deftly dodging the question. “They’re not going to get away with it this time.”

Not even brandishing a Marine sword around Mar-a-Lago could keep Trump in line. That’s probably why LaCivita says he has focused on “boring cash flow and shit” that he stands a better chance of controlling. “Trump sets the tone,” he explains. “My job is to implement the vision that he sets. My focus is making sure that the campaign and the staff and the message are functioning flawlessly—which is never the case. Politics is never the art of the perfect. It’s the art of the possible.”

Indeed, it’s LaCivita’s focus on organization, rather than any skullduggery, that could be the biggest factor in getting Trump over the line—especially given that the candidate has no hesitations doing his own dirty work. “There’s no ‘dark arts’ with Donald Trump,” Media Matters’ Matt Gertz says. “He does it all himself. The guy got up in front of the American people and asked Russia to intercede in the election and they did. There’s not something he won’t do.”

While incompetent and undisciplined staff have kept Trump from being more successful—both in the 2020 campaign and during his time in the White House—LaCivita is by all accounts extremely competent. And he’s already mounted a defensive operation to block off the vultures who see Trump’s chaos as an opportunity to gain power and push their own agendas.

In November, the Washington Post reported that outside groups like the Heritage Foundation were mapping out a strategy for Trump to staff his next administration with people happy to execute his plans for political retribution. Other news stories followed detailing plans by other nonprofit groups to vet candidates to fill a Trump White House with loyalists willing to push for mass deportations, politicize the Justice Department, prosecute his enemies, and deploy military force against domestic protests. Together, the stories painted a picture of a second Trump administration that was dark, scary, and unlikely to appeal to, say, moderate suburban women.

LaCivita and Wiles took the unusual step of publicly chastising these prominent supporters, gently encouraging them to back off, while at the same time privately urging them to counter the impression that Trump’s second term would be an authoritarian one. Their candidate did not help when, a few days later, he declared at a Fox News town hall that he planned to be a dictator “on day one.”

When the media chatter continued, the campaign issued a sterner warning. “Despite our being crystal clear, some ‘allies’ haven’t gotten the hint, and the media, in their anti-Trump zeal, has been all-to-willing to continue using anonymous sourcing and speculation about a second Trump administration,” wrote Wiles and LaCivita. “Let us be even more specific, and blunt. People publicly discussing potential administration jobs for themselves or their friends are, in fact, hurting President Trump…and themselves. These are an unwelcomed distraction. Second term policy priorities and staffing decisions will not—in no uncertain terms—be led by anonymous or thinly sourced speculation in mainstream media news stories.”

The pushback was a sign that even if the candidate may be a loose cannon, LaCivita was intent on making the campaign a tight ship. “He may have found his perfect candidate in Donald Trump,” says Elleithee. “LaCivita is the kind of operative who will let Trump be Trump and figure out how to harness that and professionalize the operation around him. I think that’s going to make this campaign operationally the strongest campaign that Donald Trump’s run so far.”

LaCivita may succeed in keeping Trump’s campaign from going off the rails and fending off grifters. But I wondered if even his well-honed messaging skills could succeed in the hardest part of his job: selling Trump to people outside MAGA world. What does Trump have to offer, say, liberals who might read Mother Jones? LaCivita replied that everyone is affected by things like inflation and the border crisis, two of Trump’s signature issues.

“Liberals want to make America great again,” he told me with a laugh, “just as much as conservatives.”