Before Georgia voted for Joe Biden, the biggest upset in recent state politics came when Democrat Lucy McBath became the first Black person to represent Newt Gingrich’s former congressional district.

Georgia’s Sixth District, home to the affluent northern suburbs of Atlanta, was long a bastion of deep-red Republicanism, represented by Gingrich for 20 years. But that changed in 2018, when college-educated white voters shifted their allegiance to the Democrats and joined with an influx of Black, Latino, and Asian Americans who’d moved to the suburbs. They teamed up to elect McBath, a political novice who had turned to activism after her 17-year-old son, Jordan Davis, was murdered by a white man in Florida in 2012, and decided to run for Congress after the Parkland high school shooting in early 2018. “The work was calling me,” she told Mother Jones that year.

McBath’s victory, which helped Democrats retake the House of Representatives, exemplified Democratic inroads in formerly red states like Georgia and the new power being exercised by communities of color in fast-diversifying Southern states. But those gains could quickly be wiped away—and districts like McBath’s eliminated—by GOP dominance of the next redistricting cycle, which will begin when the Census Bureau releases nationwide demographic data by August 16.

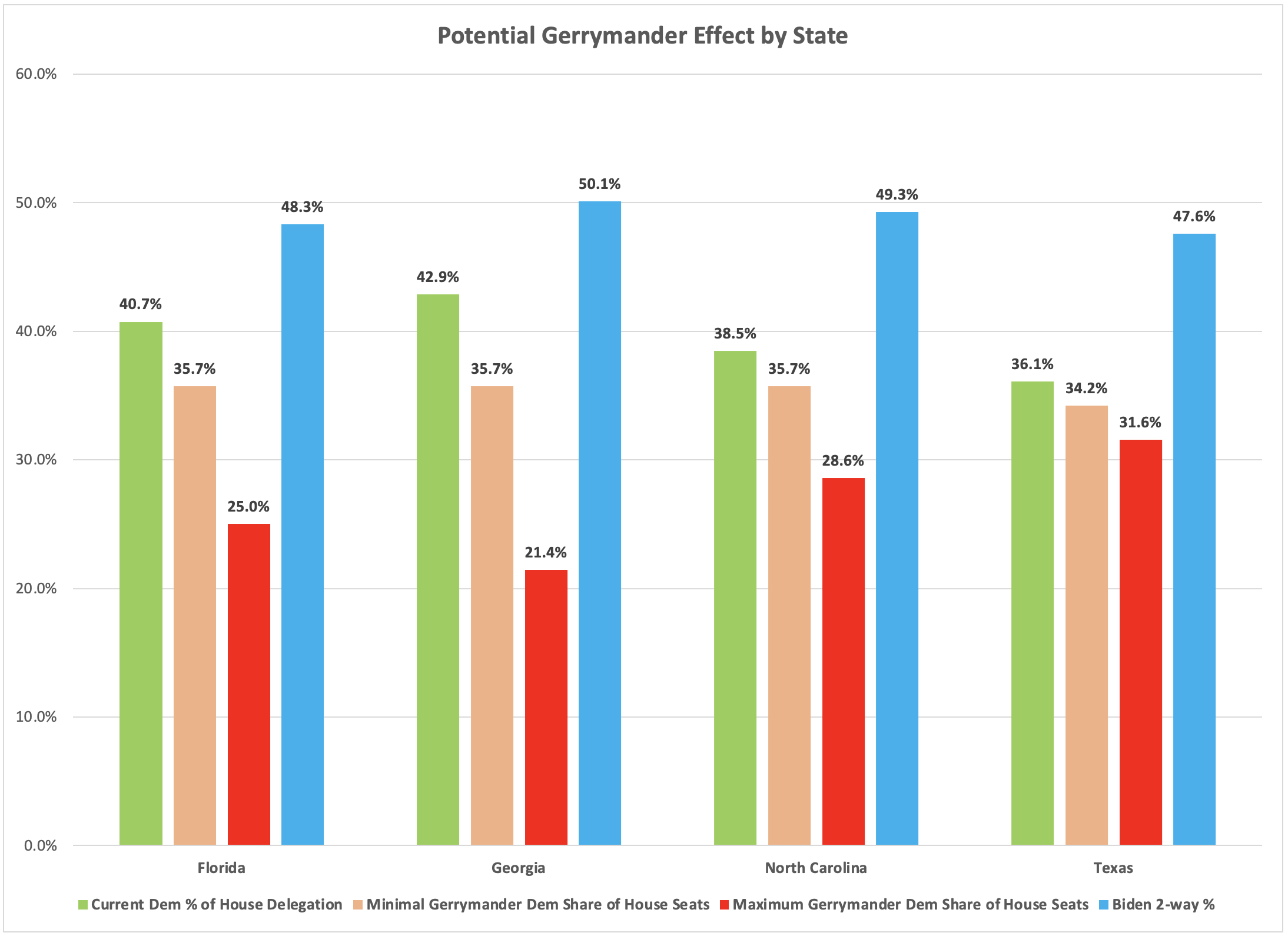

Republicans could pick up anywhere from six to 13 seats in the House of Representatives—enough to retake the House in 2022—through its control of the redistricting process in Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas alone, according to a new analysis by the Democratic data firm TargetSmart that was shared exclusively with Mother Jones. Republicans need to gain just five seats to regain control of the House.

The Republican redistricting advantage goes far beyond those four states: They’ll be able to draw 187 congressional districts, compared to 75 for Democrats. (The rest will be drawn by independent commissions or divided state governments.) But those states are at the highest risk of extreme gerrymandering, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, and they have 94 seats, roughly a fifth of the House. Republicans could draw as many as five new GOP congressional districts in Florida alone, giving them control of the House by redrawing maps in just one state. They’re also likely to gain two to three seats through new maps in Texas, one to three in Georgia, and one to two in North Carolina, according to TargetSmart.

Democratic representation under potential partisan gerrymanders compared to Biden’s vote share in 2020. Chart via TargetSmart

The bulk of the attention on voting rights this year has focused on the wave of new laws in GOP-controlled states intended to make it harder for Democratic constituencies to cast a ballot, by doing things like rolling back voting by mail and shortening early voting periods. These new voting restrictions could certainly swing a close election, but the ultimate partisan effects are unknown, whereas the new redistricting maps enacted by Republicans will have a devastating and surgical impact on Democratic representation, voting rights advocates say. “There’s no question Texas, Georgia, Florida, and North Carolina are enough to give Republicans the number of seats they need to win back the House,” says Michael Li, a redistricting expert at the Brennan Center.

GOP members of Congress have already admitted that this is their plan to win back power in 2022. “We have redistricting coming up, and the Republicans control most of that process in most of the states around the country,” Rep. Ronny Jackson (R-Texas) said at the Faith and Freedom conference in June. “That alone should get us the majority back.”

Democrats’ best hope to prevent a gerrymandering bloodbath is to pass the For the People Act, the sweeping democracy reform bill that passed the House in March but was blocked by a GOP filibuster in June. The bill, also known as HR1, has been in the news for its provisions to ban the types of state-level voting restrictions that sent Texas Democrats fleeing to Washington earlier this month to beg Congress to pass the act. But arguably more significant is its proposal to end partisan gerrymandering.

“Absent the passage of HR1,” says TargetSmart CEO Tom Bonier, “the GOP is poised to gerrymander their way to a House majority.”

Time is running out for Senate Democrats to act. States could put new maps in place by early fall, and those maps will govern congressional elections for the next decade. “There is a fundamentally increased focus on redistricting than there was in 2011, and yet as we talk about the For the People Act, people are not talking about the gerrymandering components and the importance of them,” says Eric Holder, the former attorney general under Barack Obama who in 2017 founded National Democratic Redistricting Committee to combat GOP gerrymandering efforts. Holder’s group estimates that gerrymandering could net Republicans 11 to 16 seats in Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas—higher even than the TargetSmart forecast.

The For the People Act would ban partisan gerrymandering by requiring independent commissions to draw congressional districts, as well as invalidating existing maps that have the intent or effect of “unduly favoring or disfavoring” one political party over another. Even if it’s too late to set up independent redistricting commissions before new districts are drawn, the ban on partisan gerrymandering—along with requirements in this law that prevent communities of color from being diluted—would make it much easier to challenge skewed redistricting maps in court. Though the Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that the federal courts could not review partisan gerrymandering, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that “the Framers gave Congress the power to do something about partisan gerrymandering in the Elections Clause.”

A stripped-down version of the For the People Act proposed by Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) eliminated some of the voting protections from the original version of the bill but included the ban on partisan gerrymandering. This revised measure, which is expected to be formally introduced in the coming days, may have a better shot at passing the Senate, especially if moderate Democrats like Manchin are willing to create an exemption to the filibuster for this bill and allow passage with a simple majority. (So far, Manchin has said he opposes this exemption.) “At some point we’re going to get to a binary choice between protecting our democracy and protecting an arcane Senate procedure,” Holder says of the filibuster. “At the end of the day, you’re not going to get 10 Republicans [to support the For the People Act]. This is something Democrats will have to pass.”

But that legislation will only make a difference on redistricting if enacted before the new maps take effect—giving Democrats a matter of weeks to act.

“Even Joe Manchin talks about banning partisan gerrymandering,” says Li. “Everyone recognizes there is problem that needs to be solved. What’s frustrating is they don’t understand this problem is not something that needs to be solved in the future—it’s happening now.”

According to the New York Times, White House officials have told voting rights advocates they believe Democrats can “out-organize voter suppression”—in other words, they believe they can counteract the new voting restrictions and replicate the high turnout from 2020 in the absence of new federal legislation by focusing on registration, get-out-the-vote efforts, and making sure all votes are counted. But extreme gerrymandering can negate these efforts by allowing Republicans to essentially pick their own voters in a remarkably targeted and durable way. Over the past decade, Democratic state legislative candidates have routinely won more votes than Republicans on a statewide basis in places like Michigan, Wisconsin, and North Carolina—but the GOP retained control of state legislative chambers for the entire decade. It took an unprecedented anti-Trump wave in 2018, which is not likely to be repeated any time soon, combined with court rulings striking down gerrymandered congressional districts in Texas, Florida, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, for Democrats to retake the House in 2018.

“There’s some sentiment you can out-organize voter suppression,” says Li. “You can help people get the IDs they need to vote. You can’t out-organize gerrymandering. You can’t out-organize the dismantling of a multiracial district in the Atlanta suburbs. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Holder agrees. “Gerrymandering is not a question about organizing,” he says. “You can get people to the polls, they can vote in record numbers, and if you allow unfair racial or partisan gerrymandering to occur, that can neuter the turnout.”

Indeed, if everyone voted the same way as in 2020, Republicans would take back the House simply based on their control of the redistricting process, according to research by Democratic data scientist David Shor. Banning partisan gerrymandering is the most important thing Democrats can do to prevent Republicans from retaking power, Shor says, more than policies expanding access to the ballot such as automatic voter registration, which are good for democracy but have little to no partisan impact. “This one part of the bill is probably about five times more important than the rest of the bill combined,” he says of the gerrymandering sections of the For the People Act.

The gerrymandering of the next decade could be even worse than in 2011 because of two Supreme Court decisions: the 2019 ruling prohibiting the review of partisan gerrymandering and the 2013 decision striking down the “preclearance” requirement of the Voting Rights Act that required states with a long history of discrimination, like Georgia and Texas, to submit their redistricting maps for federal approval. “Communities of color in particular will enter the next cycle of map drawing with fewer protections than at any time since the 1960s,” the Brennan Center wrote in a February report.

Republican gerrymandering is likely to blunt the impact of demographic changes that should benefit Democrats. Nearly 75 percent of the growth in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas comes from communities of color, but virtually all the new seats drawn by the GOP are likely to be held by white Republicans. As many as six Democratic representatives of color could lose their seats in these four states, according to TargetSmart. “The future of America is multiracial coalitions, and Republicans will have an opportunity to kneecap that,” says Li.

Republicans will accomplish this by concentrating Democratic voters—particularly voters of color—into as few districts as possible in the urban cores of cities like Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Orlando, and Miami, in order to maximize the Republican vote in suburbs and exurbs that still favor the GOP.

McBath’s district, for example, could be combined with an adjoining swing district in the Atlanta suburbs held by freshman Democratic Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux in order to pit the two Democrats against each other and create a safe GOP seat. Alternatively, the suburban Democratic districts could stretch further into the Trump-backing exurbs and countryside, adding more conservative white voters and imperiling both Democrats. “We’ve got a chunk of Republican voters we can put back in the Sixth,” Georgia GOP strategist Phil Kent told a local news station in April. “We can pull them from elsewhere and even it out more. So Lucy McBath…has got to worry about more Republican votes in that district.” Republicans could try the same tactics in other states by splitting apart voters of color in cities like St. Petersburg and Tampa or Winston-Salem and Greensboro in order to draw safe GOP seats.

The net effect will be to create state legislative and congressional districts that are whiter and more conservative at the very moment that places like Georgia and Texas are becoming more diverse and Democratic. In that way, gerrymandering functions as a form of voter suppression by preventing voters of color from having a full say in who controls their state and who represents them in Washington. “The way that Georgia disenfranchises African Americans is that they heavily gerrymander their state legislature,” says Shor.

Gerrymandering further entrenches the power of the very legislators who are passing new voter suppression laws, making it nearly impossible for a majority of the public to hold them accountable for their anti-democratic actions. Even as Biden narrowly carried Georgia in 2020, Trump won the median state senate district by 15 points, showing how far to the right the state legislature was compared to the rest of the state. Under a hypothetical Texas congressional map drawn by Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report to illustrate what an extreme gerrymander could look like, Republicans would have 25 seats compared to 13 for Democrats, even though Biden lost the state by only 5 points, and every GOP district would have voted for Trump by 10 points or more, making it unlikely that Democrats could win them any time soon.

“The numbers are clear,” says Lauren Groh-Wargo, CEO of Fair Fight Action, the voting rights group founded by Stacey Abrams. “If Congress does not take swift action to protect voters by banning partisan gerrymandering, then the same GOP state legislatures that are destroying our democracy with anti-voter bills and conspiracies about our elections will quickly draw Democrats out of power for a decade through unchecked gerrymandered maps.”

A GOP takeover of the House will not only derail Biden’s agenda; it raises the prospect that a GOP-controlled House would not accept the results of a contested 2024 presidential election, given that 65 percent of House Republicans refused to certify the election results in 2020. A party that took power through anti-democratic means could then dramatically escalate its effort to subvert American democracy.

“A House controlled by one political party solely because of partisan gerrymandering,” Ohio State University law professor Ned Foley wrote recently on the Election Law Blog, “could make all the difference between the survival or death of American democracy.”