On November 5, New York Times polling savant Nate Cohn appeared as a guest on The Daily, the paper’s popular podcast, to shed light on the biggest question in the Democratic presidential primary. The episode’s title: “Who’s Actually Electable in 2020?”

Cohn took to the microphone to deliver some real talk to millions of listeners: Elizabeth Warren—who at the time had just climbed to the top of the polls for the Democratic nomination—may be a weak nominee because some voters wouldn’t support a woman.

The Times had commissioned a poll measuring the top Democratic contenders against President Trump in the closely contested states that cost Hillary Clinton the 2016 election. There, Cohn explained, Warren looked shakier than both Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. “Overall, she trailed by 2 points across these states,” Cohn said. “That’s the same as Hillary Clinton’s performance. So if the election were held today, and if these results are right, Elizabeth Warren would lose to the president.”

The takeaway was unmistakable: The female candidate would again fail, just like the last one. Millions of people read about the poll, or listened to Cohn’s predictions, or listened to other pundits chew it over. Filtering through the media coverage were subtle notions that Warren and the other women running for president were inherently risky choices for a party focused on turning Trump out of office. Was Warren too angry, as Biden suggested that same day? Was she therefore unlikable? It seemed that just as Warren had begun to overtake Biden in the national polls, a riptide of pent-up, gender-based anxiety took hold of her campaign and pulled it down. Had Cohn found misogyny in his crosstabs? Or did the results reflect respondents’ fears about other voters’ willingness to vote for a woman? Had Democrats’ desperation to pick a winner created a party of amateur sexism handicappers?

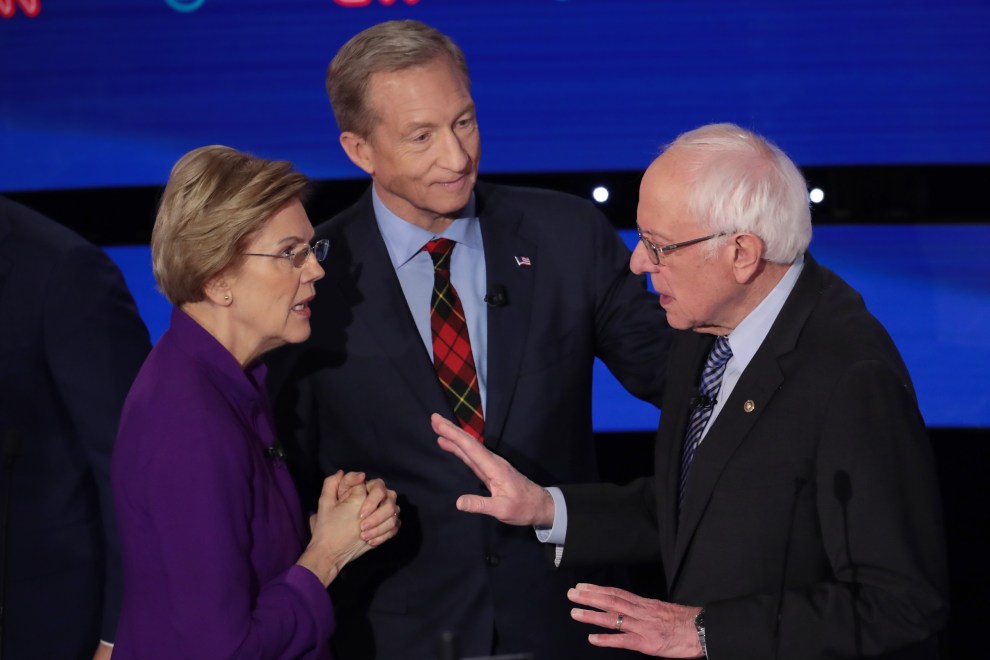

On January 13, the issue transformed from a quiet undercurrent of the primary to the national headlines. CNN reported that at a dinner in December 2018, as both Warren and Sanders were preparing to launch presidential campaigns, Sanders told Warren that a woman couldn’t win. The following day, at a Democratic primary debate hosted by the network in Des Moines, Iowa, the issue took center stage. Sanders denied his comments; Warren confirmed them. After the debate, microphones caught a testy exchange between the two: Warren declined to shake his hand, and they accused each other of having accused each other on national television of being a liar. Though the two candidates appear to have moved on, the public is still left to grapple with the question at the heart of their dispute, the one that has loomed over Democratic politics since Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016: Can a woman beat Trump?

In Madison, Wisconsin—one of the critical swing states that Trump won in 2016—Kathleen Dolan read the Times poll not as a warning against nominating a woman but as yet another bad poll scaring voters for no reason. A political scientist at the University of Wisconsin who researches the impact of gender on voter choice, Dolan says that rather than demonstrating latent sexism among voters, the survey was itself an insidious form of sexism: incredulous pundits planting the idea that a woman is not electable.

The poll may have indeed shown Biden with an edge, but given the margin of error, Cohn was wrong to claim that it showed Sanders doing any better statistically than Warren in the surveyed states, Dolan says. To her, the Times article and headline—“One Year From Election, Trump Trails Biden but Leads Warren in Battlegrounds”—were pushing a narrative unsupported by data. “Somebody chose to look at Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren being in exactly the same statistical position vis-à-vis the president,” she says, “and decided to focus on the fact that somehow she’s losing.”

The poll did something else that Dolan found deeply misguided. It asked a subset of voters who’d said they would support Biden over Trump but not Warren whether the female candidates in the race were likable—to which 41 percent of that small subset said they were not. “For people who do survey research, it’s a bad question,” she says. There were five female candidates in the Democratic primary at the time, including the polarizing Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard. How are respondents to answer that question if they found one unlikable but not the others? The Times question used “likability” as a proxy for sexism, a way to tease out whether some voters didn’t want to elect a woman president without making them say so explicitly. But it’s a clumsy stand-in for gender bias, and one that may do more to reinforce stereotypes than actually unearth voter beliefs.

As Dolan sees it, that “really flawed question” is the crux of the problem. Voters answering the survey and news consumers getting the results see that the Times chose to include the question, Dolan says, and they reason that experts “must think it’s important,” while at the same time noting it was asked only about female candidates. “So they must think that the women might be likable—but might not be.”

“That’s the sexism right there!” Dolan says. Dozens of men have lost presidential campaigns, and so far in every instance but one, Americans selected another man to try again the next time, their maleness blessedly unburdened with concerns about electability. Not only is bias clearly embedded in the question, she argues, the question itself keeps alive the very notion that it is trying to measure—that women are unlikable and therefore unelectable—setting up a self-fulfilling prophecy in perpetual motion. The electability of women remains in question because people keep questioning women’s electability.

A woman, I was told again and again, can win. The studies prove it. I’d wanted to know just how much voters were worried about the electability of a female candidate and whether those fears were grounded in real disadvantages. So I turned to political scientists who study the issue. And the results, as you would expect on any complex social issue, were both mixed and clear. A woman can win but before that she has to navigate a set of real stereotypes and biases, which are perhaps all the more acute because of Clinton’s loss. Gender equality hasn’t come as far as we hoped. For some voters, their sexism is a reason to support Trump.

“Voters are more skeptical of women’s experience and competency and therefore want to hear more about what women can do, their qualifications, and their plans,” says Kelly Dittmar, a political scientist at Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics. Women must work harder to prove their competence to voters more skeptical of their readiness yet at the same time not put off voters who expect women to be warm and collaborative.

The women running in the Democratic primary have tested a range of political personas to preempt this bias. Gabbard has an abrupt, almost stoic manner and highlights her record in the military. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) has made her legislative achievements and her record of winning in the Midwest the centerpiece of her campaign—how could anyone worry about the electability of a candidate who keeps getting elected, her campaign seems to ask. But Klobuchar’s presentation also draws on a feminine stereotype: She’s passed a lot of bills because she works with others. She’s a team player.

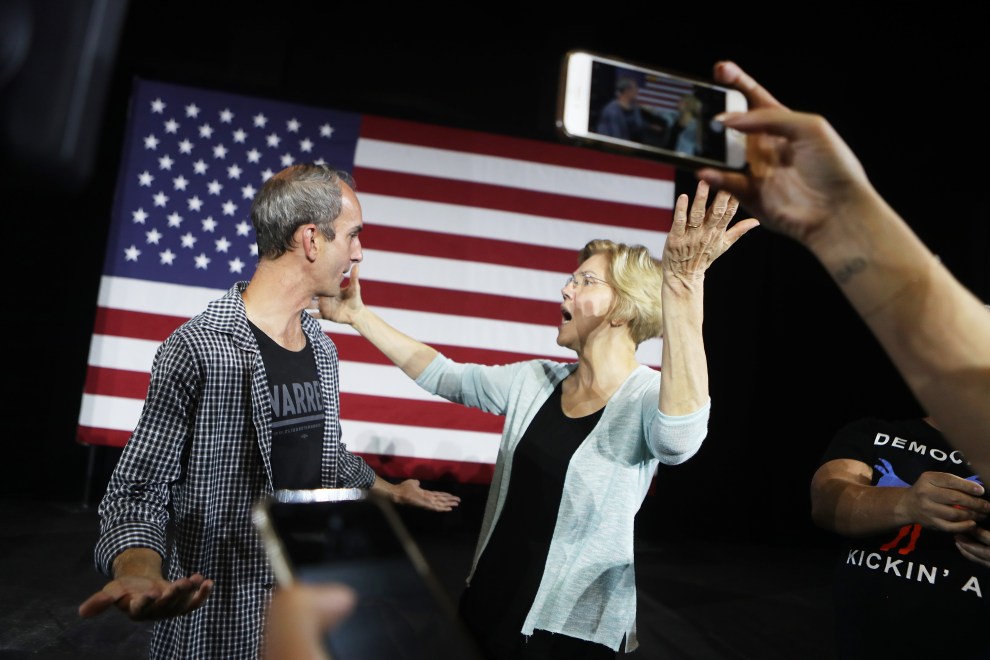

Warren faced a lot of questions in the run-up to her campaign launch about her likability—the which candidate would you like to grab a beer with? question. Is it a coincidence that in an Instagram live appearance shortly before her campaign launch, Warren said, “Hold on a sec, I’m gonna get me a beer,” walking to her fridge and returning with a Michelob Ultra? Warren is first and foremost known as a wonk. She built a campaign on the strength of her many plans, which act as a bulwark against questions about her competency and preparedness. Her famous selfie lines make for great social media and press coverage, but they’re also strategic. Who takes selfies with people who aren’t likable?

Running for office while female is “the extrapolation of every woman’s experience,” says Mary Anne Marsh, a Democratic political consultant. “You work twice as hard, you get twice as many or more credentials, you out-work everybody else, and you still get paid less.”

The candidates’ efforts to disarm gender stereotypes may not be important for the reasons we assume. Some research shows that voters aren’t concerned as much about likability when it comes to their own votes. Instead, they worry that other voters won’t pick a woman. It’s an issue of perceived electability, not actual electability—although at the end of the day they are the same thing. Dolan’s research, for example, compares people’s choice of candidate to their attitudes about gender. Negative gender stereotypes, she found, are not a main driver of voter choice—at least not at the state and congressional levels. Dolan also points to a recent study out of Finland, one of the world’s most egalitarian countries, which just swore in a 34-year-old female prime minister. Gender stereotypes and sexism remain in Finnish society, the study found, but eradicating them wasn’t necessary for a woman to become head of state.

But there’s some evidence American voters view the presidency, the top executive position in the country, in a fundamentally gendered way. Jonathan Knuckey at the University of Central Florida analyzed a major 2016 voter survey that used questions designed by social scientists to suss out sexist attitudes while also asking about voter choice for members of congress and for president. The results showed that attitudes about women were statistically significant in voter choice for president but not for the House of Representatives. “The effect of sexism on the 2016 election appears confined to presidential vote choices,” Knuckey concluded, “where the mere presence of a woman and the presence of a man who had exhibited sexist and misogynistic behavior served as the triggers in ultimately making sexism a salient and consequential determinant of vote choice.”

One study showing the magnitude of the effect at the presidential level was conducted in 2018 by Brian Schaffner, a political scientist at Tufts University, and two former colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. The researchers looked back at two polls conducted in 2016 in which they not only polled whom respondents would vote for, but also asked a set of questions similar to Knuckey’s meant to assess voters’ standing attitudes about gender. Instead of testing voters’ reactions to common media terms like “likability” or “electability,” they asked voters to react to a series of statements developed to measure hostility to women, like “Women are too easily offended” and “When women lose to men in a fair competition, they typically complain about being discriminated against.”

Unsurprisingly, those who demonstrated more hostility toward women were less likely to support Clinton. In fact, sexism had a stronger correlation with vote choice than with economic concerns. “Moving from one end of the sexism scale to the other was associated with more than a 30-point increase in support for Trump,” the study concluded. The fact that the 2016 election was oversaturated with gender stereotypes may have made sexism a more influential facet of voter choice than in previous elections, the authors concluded.

Similarly conducted surveys had the same findings. Together, they complicate the economistic reading of the 2016 election whereby Trump’s victory is ascribed to his ability to speak to the economic insecurity of Rust Belt voters, as if racism and sexism weren’t bound up with material concerns.

Schaffner has found that, even among Democrats, sexism is a factor. In a follow-up from last year in which he rated survey respondents on the same sexism scale, he found that higher sexism scores correlated with lower support for the women running in the Democratic primary.

While those studies show that sexism is real, others suggest the biggest problem is in our heads. Lean In, a group affiliated with Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, recently undertook a poll to determine if voters were ready for a woman president. While a majority responded that they themselves were ready, an even greater number said they didn’t think their fellow Americans were. The less a respondent felt the country was ready for a woman, the less likely that person was to support one of the women Democratic candidates.

Lean In also asked voters questions to assess respondents’ perception of each candidate as “presidential” and “electable,” two subjective terms that nevertheless play a role in how people assess candidates. Unsurprisingly, male candidates rated higher on both counts. But the data showed that if voters considered the men and women candidates equally presidential and electable, the men would no longer have an advantage.

“The two biggest predictors of whether voters say they’ll vote for a man or a woman who’s running in the Democratic primary is how electable and how presidential they are,” says Rachel Thomas, Lean In’s CEO. “Outdated notions of who’s electable and who’s presidential could very much get in the way of how voters vote.” In other words, the men’s advantage exists only when people believe in it.

This summer, Schaffner polled people likely to vote in the Democratic presidential primary on the traits they desired in a nominee. More than half said they wanted the party to choose a woman. But when asked who was more likely to beat Trump, the numbers flipped, with respondents concluding a male candidate had a better chance. These were the amateur sexism handicappers, the people who aren’t themselves sexist—so they say—but who worry everyone else might be and then shape their electoral preferences accordingly.

In the wake of 2016, such strategic calculations are inevitable. Trump’s campaign in 2016 was anti-woman. In the primary, he famously defended insulting comments about women by discrediting his questioner, Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly, with more vulgar sexism. He said the only woman running for the GOP nomination was too ugly to be president. He feminized his male opponents, whom he accused of being too little or too tired, and, on a debate stage he boasted about the size of his penis. He obsessively portrayed Clinton as lacking “stamina.” Then there were the stories that emerged: body shaming a former Miss Universe, forcibly kissing other contestants, and finally a tape of him bragging about attacking women. The Access Hollywood bombshell was followed by renewed accusations of assault from many women. At the end of the campaign, Clinton ran an ad highlighting all of Trump’s sexist behavior, practically daring voters to elect someone with a record of demeaning and assaulting women. It was supposed to disqualify him—instead he won.

“Every so often, society is reminded of how unequal things still are,” says Marianne Cooper, a Stanford sociologist who helped craft Lean In’s study. “For many people, particularly many women, [2016] brought into stark relief that we may not have moved as far on gender issues as one would have hoped.”

America’s recent history with Clinton places an extra burden on today’s female candidates. “People view 2016 through this lens of ‘We’ve had a female nominee, gender issues were a big part of the campaign, and we lost,’” says Schaffner. “‘We don’t want to run that same campaign again. And if we nominate a woman, we’re worried that’s the kind of campaign that we might end up in again, and that we would lose it again.’”

“A woman is electable at the presidential level—that’s proven,” Dittmar says, citing the simple fact that Clinton received nearly 3 million more votes than Trump. At the same time Dittmar warns that Clinton’s Electoral College loss did in fact buttress skepticism about female candidates’ chances—doubts that she thinks may have increased during Trump’s time in office as “he has doubled down on the misogyny and the traditional performance of masculinity and the presidency,” she says, reinforcing “people’s perceptions that this office is made for men and masculinity.” We’re left with the dizzying recursions of the electability debate—voters thinking like pundits who are trying to channel voters.

At this point, there’s little utility in relitigating 2016. There’s evidence that Clinton would have won if not for James Comey’s announcement of a renewed email investigation. Perhaps she would have won if the public had not been distracted from the Access Hollywood tape by Russia’s release of her campaign manager’s private emails. Or if Facebook and Instagram hadn’t been flooded with disinformation, particularly posts urging minorities not to vote. Kathleen Hall Jamieson, a professor of communications at the University of Pennsylvania, meticulously studied Russian interference in the 2016 election and concluded that the Kremlin played a decisive role. But there remains strong evidence that some voters were persuaded by sexism to vote against Clinton. Were their numbers greater than those persuaded directly or indirectly by the Russians? Or Comey? By campaign errors? By complacency or disinterest among Democratic constituencies? Is the misogyny even separable from the Russian meddling that preyed upon it, or from the effects of a Comey announcement that seemed to confirm so many sexist misgivings about Clinton’s competence? How do we even begin to answer these questions?

While the people I spoke with say sexism and voters’ assumptions about whether their neighbors will vote for a woman are very real, no one believed that Warren’s dip in the polls in November was caused by fears that her gender will make her a weak candidate against Trump. Instead, the main presumptive cause was Warren’s Medicare-for-All proposal. She had long supported a single-payer health care system, but in every debate moderators had pressed her to explain how she would pay for it. So did her Democratic rivals. Finally, Warren released a plan detailing how she would, while outlining a slower implementation than that envisioned by Sanders, the staunchest supporter of Medicare for All.

“Her dive in the polls is undeniably tied to her Medicare for All plan,” says Marsh, who has long observed Warren’s political career. “There’s no other reason when you look at the polling.” The plan, she posits, may have softened Warren’s support among women, who are both key to Warren’s coalition and prioritize health care as an issue. Dolan believes that the Medicare for All plan may have scared off some moderates who were supporting her; Pete Buttigieg, who has a less-ambitious health plan, saw his poll numbers rise after her rollout. Tufts’ Schaffner hypothesized that Warren may have appeared shifty on the issues, reminding voters of her evasive claims to Native American heritage, which in what was a truly botched political decision blew up a year before, when she took a DNA test to try to substantiate them. There are also natural ebbs and flows in primary elections. Candidates rise, get attacked and scrutinized, then subside. Several of the experts believed Warren merely faltered as part of the routine shifts in a large primary field.

I am not entirely convinced by these explanations. Increasingly, I think Warren’s November decline is the perfect encapsulation of the challenges women candidates face—challenges that are real but that are significantly magnified by fictions in our heads.

Warren did not surprise anybody by coming out with a Medicare for All plan; she had supported the idea for years, and finally backed up that support with a concrete funding proposal. Her proposal was entirely in keeping with the central policies of her campaign: tax the rich and big businesses to pay for universal services. Why was such an in-character move seen as so negative? Could that alone explain a drop from 26 percent in the polls to 14?

To voters already unsure about the electability of a woman, any error can reinforce suspicions about her viability. “The kind of news and polls that would be speed bumps for most male candidates become potholes—or worse, sinkholes—for women candidates,” says Marsh. Warren may have more plans than any candidate, but when one of her policies received extra scrutiny, voters balked.

When the issue of women’s electability came up in the debate this month, Warren finally had a chance to address it, not just in speeches she has given about other trailblazing women or pinky-swears with young girls in her selfie lines, but directly. Warren was prepared with a robust argument not only about her and Klobuchar’s real-world records of winning elections, but also about the country’s history of taking a chance on a candidate and proving doubters wrong. “Look, don’t deny that the question is there,” she said. “Back in the 1960s, people asked, ‘Could a Catholic win?’ Back in 2008, people asked if an African American could win. In both times the Democratic Party stepped up and said yes, got behind their candidate, and we changed America. That’s who we are.”

Discussing sexism can be self-defeating: Talk about electability or likability, and you perpetuate doubts about a candidate’s chances. Even my writing about the issue now risks planting seeds of unwarranted doubt. But, insidiously, left in the shadows, misogyny goes unchecked. Whether Warren or Klobuchar wanted to address this issue head on or not, they are now running in that reality.

How Warren and Sanders’ recent dispute will affect the primary remains unclear. It seems to have invited more gendered attacks against Warren, including the pro-Sanders hashtag #WarrenIsASnake. But a world in which voters hear the issue addressed directly might in fact be better for female candidates. “A lot of our bias against particular groups is implicit,” says Melanye Price, a political scientist at Prairie View A&M University. “It sometimes just flies by without us really interrogating it.”

But research has shown that when implicit biases are uncloaked and questioned, people can choose to abandon them. This was true in the 1980s, Price explains, when research indicated that political strategies appealing to racial bias lost potency after they were called out. “Once you get past ‘Why do you think that?’ you start to think about ‘What are some of the alternatives?’ And I really don’t think there’s any other another way of going at this woman-for-president thing.”

“I don’t think that things change or move forward without talking about what’s happening,” Cooper says. Voters considering a woman have a choice, she adds. “It’s going to be harder for them to win. But they also can win. Those different takes are all true. It’s just about the world we want to live in.”

Voters may decide it’s too hard and the risk is too great, that 2016 was too ugly and they are too tired to endure another sexism-saturated election cycle. Indeed, the latest polls from Iowa and New Hampshire suggest the remaining women have a narrow path to sustain their candidacies much further.

This may be one of Trump’s greatest triumphs over women: a certainty that a woman cannot defeat him or any male presidential candidate. It’s not true, but it can be believed into existence.