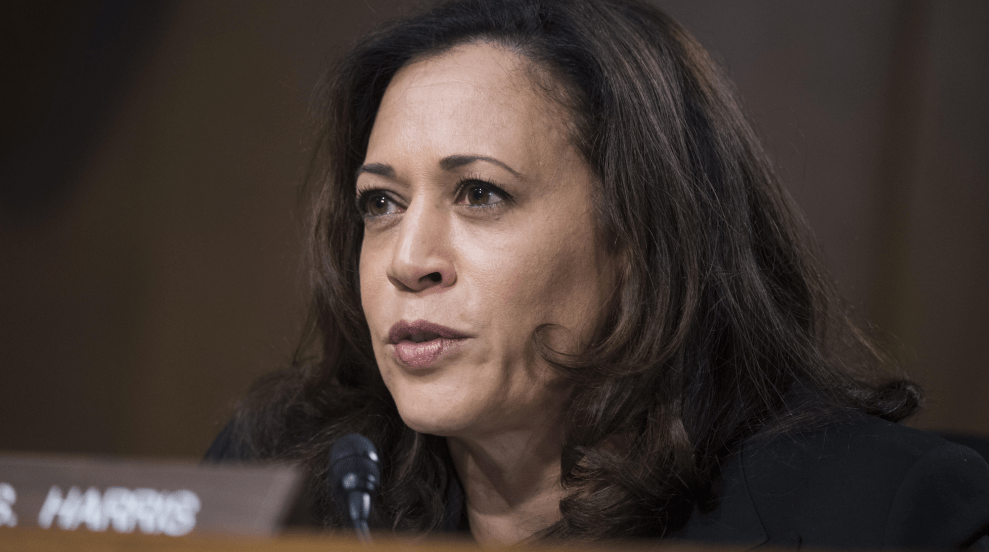

Maya Harris celebrates as her sister, Kamala, is sworn in as attorney general of California in 2011.Anne Chadwick Williams/AP Photo

In the thick of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign for president—when the candidate tried and often failed to land her message of criminal justice reform with young voters of color, when activists were calling on her to account for her previous support of her husband’s crime bill that devastated black communities two decades earlier, when the terms “mass incarceration” and “new Jim Crow” were becoming the buzzwords to define the wreckage Clinton herself was said to symbolize—Maya Harris would sit back at campaign headquarters in Brooklyn and sigh. She didn’t just know the issues. She helped edit the book on them. Sometimes the passages being tweeted at her people were the exact words she’d pored over, draft after draft, in The New Jim Crow, written by her longtime friend from law school, Michelle Alexander.

Harris was one of three senior policy advisers to Clinton in 2016, responsible for criminal justice reform, immigration, and reproductive health. It was her first official position on a political campaign, and she was a fairly unorthodox operative. A biracial black woman from Oakland, Harris had been a bookish kid who became a single mom at 17. She finished undergrad at the University of California-Berkeley and then law school at Stanford with her young daughter in tow before becoming one of the youngest-ever law school deans, at Lincoln Law School in San Jose, California, when she was just 29 years old. She’d go on to lead the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California and earn a reputation as one of the most respected civil rights advocates in the country. Along the way she would counsel other young black mothers on how to strategically utilize their support systems for necessities like child care while they worked or finished school.

“If you are fortunate to have opportunity, it’s your responsibility to make those opportunities available to other people as well and to use your power, your privilege, your position to improve lives for other people,” she said in a 2012 discussion.

Now, Maya Harris faces what is arguably the greatest challenge of her career: chairing the presidential campaign of her older sister, Kamala. Baked within that is the seemingly arduous task of building a coalition of support among racial and criminal justice advocates, many of whom are weary of Kamala’s record as a career prosecutor—first for Alameda County, then the city of San Francisco, and later as district attorney for San Francisco and eventually attorney general of California.

In the few weeks since Kamala announced her historic run for the presidency, her candidacy has been the tale of two divergent perspectives on the left: Either she’s a “cop” who takes unusual joy in punishing poor black mothers—as at least one widely shared tweet thread bluntly argued—or, as suggested by the slew of home state endorsements she’s earned from California politicians, she’s a seasoned political veteran with just enough national standing and charisma to meaningfully take on Donald Trump. That she chose her sister to lead her campaign speaks to how central family, and criminal justice reform, have been in both their lives and will be in their futures. But it also speaks to how Kamala will likely address the swirling controversies over how her work has impacted low-income black communities and how the lessons from Clinton’s 2016 campaign will either help or hinder her bid for the White House.

The sisters, who are two and a half years apart, have by all accounts always been close. They were raised in tight-knit black communities in Berkeley and Oakland by their immigrant Indian mother, Dr. Shyamala Gopalan, a cancer researcher. But their careers have existed on distinct and, at times, colliding paths.

Maya is widely respected in progressive criminal justice circles both for the official positions she’s held and the behind-the-scenes work she’s done that has often gone unacknowledged. In 2014, while a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, she wrote an influential paper on women of color as a growing force in the American electorate. It proved to be prescient; one of the key storylines after the 2018 election was the reliability of black women voters for the Democratic Party. High-profile candidates like Stacey Abrams made it a key part of their campaigns, and black women in Alabama were largely credited with Democrat Doug Jones’ victory over Republican Roy Moore for the Senate a year earlier. “Her paper put a finer note that also means you have to figure out what women of color need and want and make sure that your policy recommendations are responsive to those needs,” says Danyelle Solomon, who now leads race and ethnicity policy at the Center for American Progress.

Meanwhile, for decades, one of her closest friends was Alexander, the civil rights lawyer and academic whose 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, helped usher in an era of reevaluating tough-on-crime policies that landed generations of poor black people behind bars. In the book’s acknowledgements, Alexander praises Maya for reading several drafts of the book and “never tiring of the revision process.” But until Kamala was elected to the Senate in 2016, incarcerating people was a job requirement for her, one that she has tried, and sometimes failed, to fully own up to since announcing her run for president.

“Maya has always been more of an advocate, while Kamala has chosen to work within some of the most systemically racist institutions in the country,” says Lateefah Simon, a longtime family friend who also ran a program that aimed to keep people charged with first-time nonviolent offenses out of jail in Kamala’s district attorney’s office. The decision to go into law enforcement was one that Kamala described on many occasions as having to “defend…like one would a thesis” to her family. “There’s an important role to play on the outside, banging down the door, on bended knee, trying to change the system,” she recounted in an interview in 2018 on the popular hip-hop morning show the Breakfast Club. “But we also have to be inside the room where the decisions are being made.”

According to two people who were close to Maya at the time, she took a long time to decide whether to join Clinton’s campaign. She had her work cut out for her. Clinton was widely criticized for her support of her husband’s tough-on-crime policies in the 1990s. And her use of the term “superpredator” to describe young “gangs of kids” in the criminal justice system while advocating on behalf of the 1994 crime bill became a flashpoint for black activists who had mobilized under the banner of the Movement for Black Lives.

It was Maya’s idea to bring Clinton to a closed-door, sit-down meeting with grieving black mothers in Chicago who had lost their children to gun violence or police abuse. That group of mothers included Sybrina Fulton, whose son Trayvon Martin had been shot dead in 2012; Gwen Carr, whose son Eric Garner was choked to death by a New York City police officer in 2014; and Lucy McBath, whose son Jordan Davis was killed by a white vigilante at a Florida gas station months after Martin’s death made national news.

It was a soft touch.

While it was viewed cynically by many already deeply skeptical of Clinton, the move still had a big impact. The group of women, dubbed the Mothers of the Movement, became an important symbol to black voters. Clinton devoted nearly an entire chapter to the meeting in What Happened, her book about the campaign. It was heavily covered by the national press. “She is a mother and she is a woman and I felt she understood where we were coming from,” Samaria Rice, whose son Tamir was shot in 2014 by an officer in Cleveland, told CNN of Clinton. McBath, who was recently elected to Congress, noted that it was a moment that helped give her the courage to eventually run for office. “Serving my community, saving people’s lives—that’s my life,” McBath told me about the experience. “I never looked back.”

In another important step, Color of Change, one of the nation’s largest online civil rights organizations, was among several groups that successfully lobbied the Clinton campaign to “stop using money from private prisons,” says its executive director, Rashad Robinson. “That was a campaign that we ran, [and] I don’t believe that campaign would have went the way it did without Maya,” he adds.

Even still, Clinton’s campaign typically failed to fight against the perception that she could not put together a team that was truly progressive on issues of race and criminal justice. In one instance, Clinton released a $2 billion proposal to undo the so-called school-to-prison pipeline. The plan would have directed school districts to move away from harsh disciplinary practices, such as suspensions, which disproportionately affect black girls and boys. She also called for spending $20 billion on youth jobs and $5 billion on reentry programs for formerly incarcerated people, and the plan was widely, though not universally, embraced. Black activists, particularly during the harrowing primary, ultimately would not let Clinton move past her now-infamous superpredators remark:

Some criminal justice advocates think the impact Maya had on the campaign was significant, but ultimately limited; the narrative that Clinton was not an ally for black communities was so deeply embedded in how certain voters saw her, they note, that it was hard, if not impossible, to fully overcome. “I think by the time Maya got to her campaign [in spring 2015], a lot of that was baked in,” says Robinson. “At the end of the day, it’s the candidate who’s running [and] it’s the candidate who has to tell a compelling, believable, and full story for people about where they’ve been and where they’re headed.”

The same, of course, is true for Kamala. And though it’s still the beginning of the 2020 campaign season, some in the criminal justice world remain deeply skeptical of her record, and they aren’t willing to chalk it up to how much the conversation on criminal justice has changed in recent years.

“Kamala Harris’ last role in law enforcement was January 2017, so it’s not ancient history; it’s pretty recent,” says Sarah Lustbader, a former public defender in the Bronx who now works as senior legal counsel at the Justice Collaborative, a left-leaning research nonprofit. “It’s not like this was a different time, [because] she was taking a lot of these stances when the rest of the country had moved on. That’s worrisome to a lot of people who care about criminal justice and fairness.”

But so far there’s reason to be optimistic Kamala can succeed where Clinton didn’t—and that Maya can help her do so. Kamala’s campaign rollout has been universally praised by the political establishment, including by the president she’s looking to unseat. That rollout included a massive show of force with a 20,000-person rally in Oakland. As she works to get criminal justice advocates on board, Kamala will likely need a softer and less visible touch—and perhaps something like a closed-door reckoning with key stakeholders, similar to the crucial Clinton meeting in Chicago, could actually do the work of changing minds. And what’s more, says LaDavia Drane, Clinton’s director of African American outreach in 2016, “I don’t think you can discredit the fact that this campaign has two black women at the top”—another possible advantage for the campaign in proving its sincerity.

Other people, meanwhile, hope Kamala can draw in more progressive support by highlighting the type of team she can build. After Trump’s election, Maya became a political analyst on MSNBC. Despite the spotlight conflicting with her wonkish, behind-the-scenes nature, Kamala supporters would like to see the public-facing role continue—particularly as it can be considered proof of a potential lesson learned from 2016: Let the public know who’s writing the policies, not just who’s announcing them. And while the campaign is still in its early stages, Kamala’s ability to prove that she can build a team of advocates—led, yes, by her sister—may be just what she needs to signal where she stands on the issues and rebuild the bridges that were burned in the past.

“Maya has been a civil rights lawyer for 20 years,” says Simon, “and will no doubt be a force as Kamala develops and implements policies to radically transform criminal justice in this country.”

Kamala is arguably the strongest contender right now in an already crowded field of Democratic hopefuls. Her message of fairness and democracy will likely resonate with many voters in the primary, and she already appeals to a broad swath of women and people of color. But it’s important to remember that 4.4 million people who voted for Barack Obama in 2012 didn’t bother to vote in 2016. Many of them were black, and they were vocal about their concerns during that year’s primary. The challenge that Kamala—and Maya—now face is to address those concerns head on.

“They’ve got to tell a story from [Kamala’s] time as district attorney and time as attorney general while the country was changing, before Black Lives Matter, [and address] what has changed, what looks different,” Robinson says. “I think that story has to be told fully and people have to believe it.”