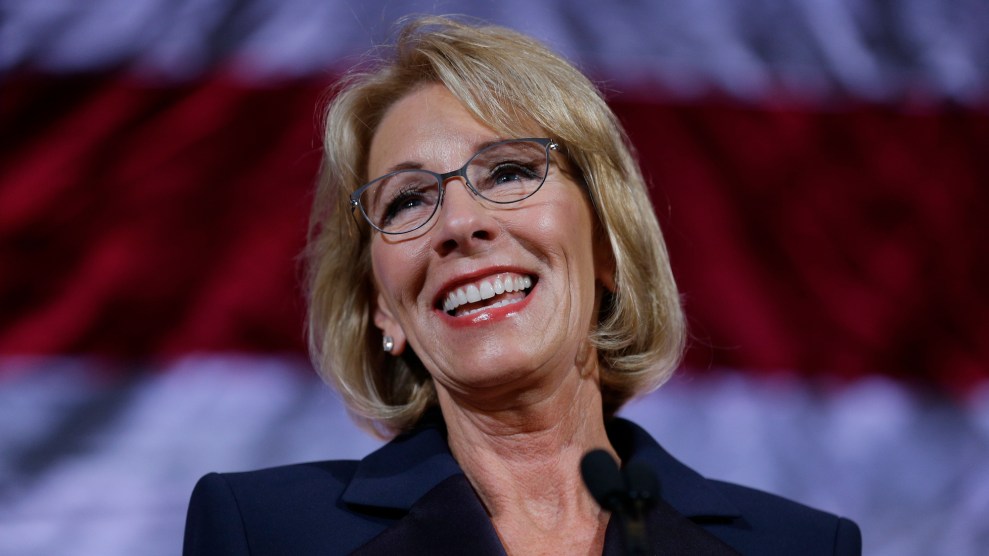

Alex Brandon/AP

Ever since Education Secretary Betsy DeVos met with a men’s rights group last year to discuss campus sexual assault policies, advocates for student victims of sexual violence have feared she would change federal regulations to put the interests of accused abusers over those of survivors. On Friday, those fears were realized, when the Education Department formally announced proposed rules governing how K-12 schools and universities should deal with allegations of sexual assault and harassment.

The proposed measures, which the Education Department can make final after a 60-day public comment period, limit what counts as “sexual harassment,” decrease schools’ liability for not addressing sexual harassment or violence, and allow schools to make it harder for survivors to prove they experienced a sexual assault.

“My focus was, is, and always will be on ensuring that every student can learn in a safe and nurturing environment,” DeVos said in a statement Friday. “Every survivor of sexual violence must be taken seriously, and every student accused of sexual misconduct must know that guilt is not predetermined.”

The changes have been in the works for more than a year—since last September, when DeVos rescinded important Obama-era documents that explained how the federal government expected schools to follow Title IX, the law prohibiting sex discrimination in federally funded education, when responding to sexual assault complaints. One of those documents, known as the 2011 Dear Colleague Letter, heralded the start of a movement by student survivors and activists to raise awareness of sexual assault on college campuses and hold schools accountable for ignoring it or covering it up. DeVos replaced the Obama-era directives with interim regulations, many of which would be codified in the formal rules proposed on Friday.

Among other measures, DeVos’ proposal would give students accused of sexual misconduct the right to cross-examine their accusers in a live hearing, through a lawyer or other adviser. (The Obama-era guidance had discouraged cross-examination, fearing it would be traumatizing for survivors.) The rules would also allow schools to raise the standard of proof that an alleged incident occurred. Schools wouldn’t have to act on accusations of sexual harassment unless they were “severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive” enough to interfere with a student’s ability to access an education. (Under the old guidance, the department considered sexual harassment to be “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature.”) And, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education, schools might be permitted to ignore allegations about incidents that occur off-campus, or outside their education programs—the rules are not clear—even though many sexual assaults take place in off-campus housing.

Backlash to the proposal was swift. Fatima Goss Graves, who leads the National Women’s Law Center, told ABC News that her group would fight to keep the new rules from going into effect. “Attacks on Title IX are attacks on students’ dignity and safety, and we will not tolerate it,” she said. Former vice president Joe Biden, who led a White House campaign to prevent campus sexual assault, slammed the proposal, saying it would discourage students from reporting sexual assault and schools from investigating it.

“Today’s proposed rollback would return us to the days when schools swept rape and assault under the rug and survivors were shamed into silence,” Biden wrote on Facebook. “We must speak up and make clear that we will not allow this Administration to take us backwards.”