Charles Dharapak, Pool/AP

On Monday, the Supreme Court struck down a North Carolina congressional map that packed African Americans into two districts and reduced their voting power elsewhere. The ruling was a decisive blow against the use of race in drawing district lines and a victory for voting rights advocates who argued that the map violated the Constitution’s 14th Amendment. But it also shed light on the court’s thinking about an even more politically consequential issue, and one that the court is likely to consider soon in multiple major cases: gerrymandering aimed at boosting a political party.

Sweeping into power in statehouses across the country in the 2010 wave election, Republicans had the good fortune to arrive at the time of decennial redistricting. This meant that many political maps in 2011 were drawn by GOP-controlled legislatures, particularly, but not exclusively, in the South. These legislatures did not hesitate to draw maps that favored Republicans. North Carolina, for example, created districts that gave Republicans a 10-3 advantage in its congressional delegation for the next six years, even as the statewide vote was split roughly equally between Democrats and Republicans.

Numerous lawsuits have been filed over those maps, raising serious questions about gerrymandering, politics, and race. Using race to draw district lines is unconstitutional without a compelling government interest—for instance, to protect the voting power of minorities—while partisan gerrymandering is considered permissible, at least up to a point. But given that party affiliation these days breaks down largely along racial lines, when do attempts to secure party dominance morph into racial gerrymandering? And when does partisan gerrymandering become so extreme as to be unconstitutional?

In its majority opinion and dissent in Monday’s case, the Supreme Court hinted at where it might come down on these two questions, which will play a big part in redistricting in 2020 and in the political power of minority voters and the Democratic and Republican parties.

First, there is the question of how to distinguish between a racial gerrymander and a partisan gerrymander. This question is particularly critical in Southern states, where minorities vote reliably Democratic. In the North Carolina redistricting case decided on Monday, the state contended that it packed African Americans into one of its congressional districts not because of their race but for partisan gain. It’s not the only state to make this argument. Texas recently defended its 2011 congressional district map as a partisan gerrymander. “In 2011, both houses of the Texas Legislature were controlled by large Republican majorities, and their redistricting decisions were designed to increase the Republican Party’s electoral prospects at the expense of the Democrats,” lawyers for the state wrote in a brief in the case. “It is perfectly constitutional for a Republican-controlled legislature to make partisan districting decisions, even if there are incidental effects on minority voters who support Democratic candidates.”

The Supreme Court took on this question directly in Monday’s decision. In what election law expert Rick Hasen described on his blog as “two bombshell footnotes,” Justice Elena Kagan addressed the so-called “race or party” question in her opinion for the majority. “A plaintiff succeeds at this stage even if the evidence reveals that a legislature elevated race to the predominant criterion in order to advance other goals, including political ones,” she wrote in one footnote. In the other, she stated, “As earlier noted, that inquiry is satisfied when legislators have ‘place[d] a significant number of voters within or without’ a district predominantly because of their race, regardless of their ultimate objective in taking that step.”

Hasen interprets these notes to mean that “the sorting of voters on the grounds of their race remains suspect even if race is meant to function as a proxy for other (including political) characteristics.” This is now part of a precedent-setting opinion. And notably, Justice Clarence Thomas, who joined the liberal justices in the majority on this case, wrote a concurrence that does not squabble with either footnote.

Hasen explains that this will make it much harder for Southern states, where race and party affiliation are closely correlated, to defend their gerrymanders. “Holy cow this is a big deal,” he writes. “It means that race and party are not really discrete categories and that discriminating on the basis of party in places of conjoined polarization is equivalent, at least sometimes, to making race the predominant factor in redistricting.” Not everyone agrees on how to interpret these footnotes, however. Justin Levitt, a voting rights expert and former Justice Department official during the Obama administration, wrote that the footnotes simply restated the accepted principle that discrimination in the furtherance of another goal is still illegal discrimination. “Even if it’s entirely lawful to try to get rich, it’s not lawful to intentionally steal from someone else in order to do so,” he explained.

Whether the court has indeed signaled a new approach to drawing the line between race and party considerations is likely to be tested soon. In March, a three-judge district court panel found that the Texas Legislature had unconstitutionally used race in drawing its congressional map. But one dissenting judge argued that what Texas had done was in fact a constitutional partisan gerrymander. That case will come before the Supreme Court as soon as the next term. “Most immediate impact of today’s NC redistricting decision may be in TX,” tweeted Marc Elias, the lawyer who successfully argued against the North Carolina gerrymander. “Court strongly signaling Texas should voluntarily redistrict.”

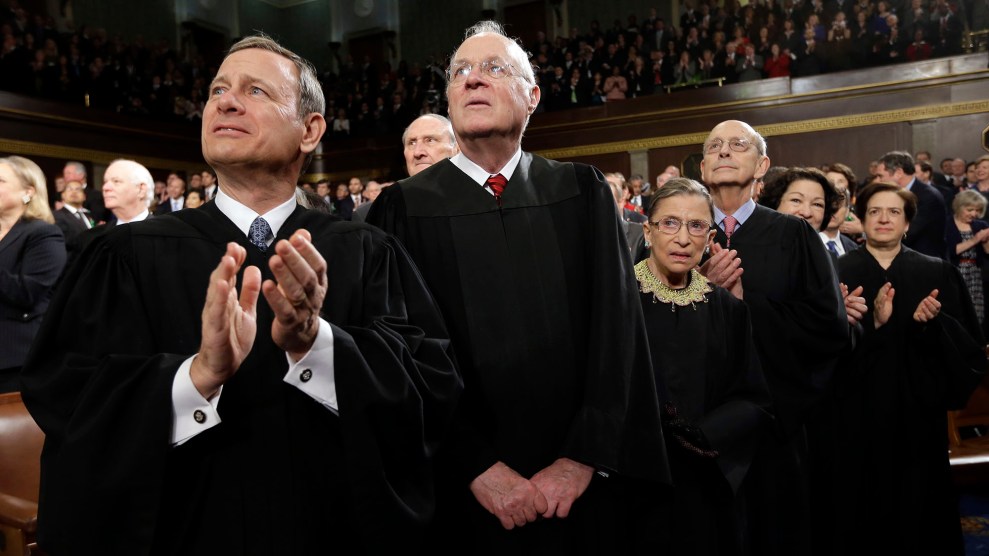

The conservatives on the court—minus Thomas—vehemently disagreed with Kagan’s treatment of race in the ruling. In his dissent, Justice Samuel Alito warned against confusing racial gerrymandering for partisan gerrymandering, arguing that the latter is a protected right of the states. “[I]f a court mistakes a political gerrymander for a racial gerrymander, it illegitimately invades a traditional domain of state authority, usurping the role of a State’s elected representatives,” Alito wrote. “This does violence to both the proper role of the Judiciary and the powers reserved to the States under the Constitution.” Notably, not only Chief Justice John Roberts but also Justice Anthony Kennedy, the expected swing vote, signed onto this dissent.

Kennedy’s position is a source of particular concern for liberals fighting extreme partisan gerrymandering. The Supreme Court has previously left the door open to claims that partisan gerrymandering, taken too far, is unconstitutional. In particular, Kennedy has shown an interest in finding a standard for courts to intervene in partisan gerrymanders—but thus far has rejected attempts by plaintiffs to find a workable standard. In a 2004 case, Kennedy sided with the conservatives to uphold a partisan gerrymander in Pennsylvania, although he suggested that the court should remain open to future challenges.

The Supreme Court is expected to take up one such challenge this fall in a case out of Wisconsin. The state’s Republican Legislature—another product of the 2010 elections—went so far in gerrymandering the state House that in 2012, Democrats won a third fewer seats than Republicans despite winning the popular vote in the state. In November, a district court struck down the map, and voting rights advocates were cautiously optimistic that the Supreme Court would do the same.

But by signing onto Monday’s dissent, Kennedy signaled that he believes partisan gerrymandering is a protected right of state legislatures.

This quote from the dissent does not bode well for plaintiffs in the Wisconsin partisan gerrymandering case /10 pic.twitter.com/XW2fNxLhpV

— Michael McDonald (@ElectProject) May 22, 2017

Formerly swaying Justice Kennedy signed to dissenting opinion partisan gerrymandering okay. There went the decisive vote to check abuse /11

— Michael McDonald (@ElectProject) May 22, 2017

Although Thomas joined the liberals in the North Carolina case over the use of race, that would not preclude him from ruling in favor of partisan gerrymandering in the Wisconsin case. In the past, Thomas has come down on the side of allowing partisan redistricting. Add Neil Gorsuch, who joined the court in April and sat out the North Carolina case, and there’s a conservative majority that believes that partisan gerrymandering is primarily states’ business.

If there is a ray of hope for voting rights advocates, it’s that while most gerrymandering cases are premised on the 14th Amendment’s equal protection guarantee, the Wisconsin case was decided largely on First Amendment grounds. Specifically, the court found that the Republican Legislature had minimized the impact of Democratic voters in the state, a form of retaliation against their 1st Amendment right to freedom of association. Put another way, the district court found that the Legislature had minimized the voting rights of citizens based on their party affiliation or voting history, a form of discrimination based on their expression and association.

Kennedy, who is known to have a particular soft spot for First Amendment claims, has suggested in the past that this might be the way to win him over when it comes to partisan gerrymanders. “The First Amendment may be the more relevant constitutional provision in future cases that allege unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering,” Kennedy wrote in his concurrence in the 2004 case. “After all, these allegations involve the First Amendment interest of not burdening or penalizing citizens because of their participation in the electoral process, their voting history, their association with a political party, or their expression of political views.”

That was 13 years ago. By siding with the conservatives in the North Carolina case, Kennedy has made voting rights advocates nervous about where he stands today.