Evan Vucci/AP; Alex_533/iStock

“See the little pair of shoes?” Kerry Starchuk brings her minivan to a halt before a sprawling manse with antebellum columns and a cast-iron fence and points to the front door. Sure enough, next to the welcome mat sits a solitary pair of clogs. Realtors do that, Starchuk tells me, “to make it look like someone is living there.” But a quick survey of the property spoils the ruse. The blinds are drawn. The lawn is overgrown and the capacious circular driveway is empty. Still, Starchuk credits the effort. “Some of the houses, you drive by and they haven’t even picked up their mail.”

It’s midmorning on a Saturday in Richmond, a suburb of Vancouver, British Columbia, and this is maybe the 20th example we’ve seen of what locals call the “empty-house syndrome“—homes purchased by foreign nationals, many of them wealthy Chinese, and left to sit vacant. Some will eventually have occupants; Vancouver is a top destination for well-heeled emigrants. But often, the new owners treat the houses as little more than vehicles for spiriting capital out of China. By one recent estimate, 67,000 homes, condos, and apartments in the Vancouver metro area, or about 6.5 percent of the total, are either empty or “underused”—an appalling statistic, given a housing market so tight that rental vacancy rates are below 1 percent. Hence the shoes: To shield absentee owners from public opprobrium, niche firms specializing in “vacant-property maintenance” will arrange elaborate camouflages—everything from timed light switches and “garden staging” to artful props, like pumpkins at Halloween and wreaths at Christmas.

Yet such tactics can’t mask the emptiness of the houses or the ghost town vibe of entire neighborhoods. Here, for example, despite the sunny weekend weather, we’ve seen few pedestrians and no children—just contractors and realtor-looking types in late-model BMWs. Steering us around a contractor’s panel van lettered in Chinese, Starchuk tells me, not for the first time today, “I feel like a foreigner in my own country.”

Comments like that don’t always go over well in a city with a huge immigrant population and a proud self-image as a hub of progressive internationalism. But in fact, many members of Vancouver’s large Chinese Canadian community are just as resentful of the behavior of the city’s ultrawealthy Chinese newcomers and the way their presence has altered everyday life. If anything, both Starchuk’s impolitic complaints and the sharp reaction to them only serve to highlight the messy social realities of a city that has been turned inside out by the imperatives of global capital.

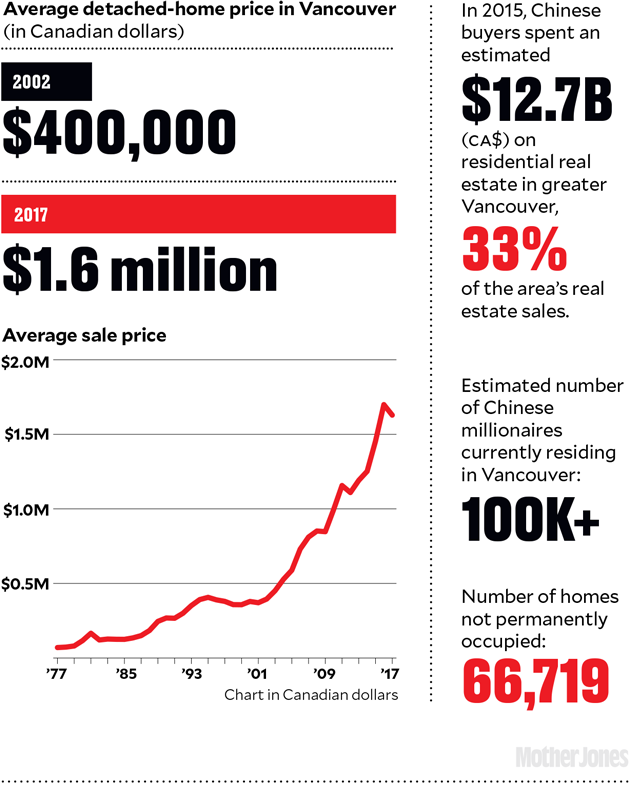

For wealthy Chinese, Vancouver has emerged as the perfect “hedge city”—scenic, cosmopolitan, with good schools, a long-standing Chinese community, and an undervalued (by global standards) real estate market where capital can be sheltered against mounting economic and political uncertainties back home. In 2015 alone, according to estimates by Canada’s National Bank Financial, Chinese purchases of real estate in the Vancouver metropolitan area amounted to nearly $10 billion, or a third of the total dollar amount spent on city real estate. (Figures are in US dollars unless otherwise noted.) So popular is Vancouver among hedgers that local real estate firms send Mandarin-speaking recruiters to Chinese cities to entice buyers to take bus tours of Vancouver’s upscale neighborhoods.

But for many longtime residents, Vancouver’s evolving role as a giant safety deposit box for China’s elite has been profoundly destabilizing. Thanks in part to foreign capital, home prices here have more than doubled since 2006. In one 12-month period (mid-2015 to mid-2016), the median price for a single-family house jumped nearly 40 percent, to $1.17 million, making Vancouver almost as expensive as San Francisco, but with a job market that is far less varied and robust.

Last August, after largely ignoring the impacts of foreign investment, British Columbia’s ruling Liberal Party enacted a 15 percent tax on non-Canadian home purchases in the Vancouver area. But while the tax has brought some relief (in January, prices for single-family homes were down 18.9 percent from their pretax peak), it has done little to assuage public anger. Some of that fury, inevitably, has taken on xenophobic undertones—a painful turn for a city that has worked hard to overcome a century-old legacy of anti-Asian attitudes. Shortly after the US election, Richmond residents found their neighborhoods littered with flyers bearing an ominous message: “Step aside, whitey! The Chinese are taking over!”

Yet most of the rage has focused on political leaders and their international pretensions. Because in fact, politicians here didn’t merely ignore the impact of foreign investment; until recently, they vigorously encouraged it, as part of a poorly conceived plan to pump up Vancouver into a global “gateway city.”

Vancouver’s wounds may have been self-inflicted. But this won’t be the last urban housing market blown up by the trillions of dollars now pouring out of emerging market economies. Given the attractiveness of urban real estate to foreign investors—and the temptation that outside capital poses for cash-strapped cities—the Vancouver debacle should be a required case study for urban politicians, activists, and citizens everywhere.

As is often the case in stories of grand civic ambition, Vancouver’s current crisis began as a well-meant solution to prior calamity. In the early 1980s, the city was reeling from years of recession and the collapse of western Canada’s timber- and mining-based economy. Unemployment in British Columbia hovered between 10 and 15 percent. Vancouver’s housing market had lost 40 percent of its value. Businesses were closing and the city “was on the way to becoming the Detroit of the Pacific,” says Andy Yan, a University of British Columbia urban planner who has closely studied the regional housing market. So local and federal officials conceived of a plan to modernize the city’s economy by recruiting foreign business expertise and capital.

Dubbed the Pacific Rim strategy, it was a variation on a model developed in the United States during the postwar era. In the 1950s and ’60s, Stanford University had used the promise of cheap land to woo technology firms to a new industrial business park that became the core of Silicon Valley. Likewise, Phoenix deployed a “business friendly” strategy of heavy deregulation, low taxes, and aggressive anti-union policies to lure hundreds of manufacturing and tech firms from ailing Rust Belt cities.

Vancouver’s Pacific Rim strategy was even more grandiose. Recruitment efforts focused not on North America, but on booming Asia. And instead of courting companies, Vancouver went after individual investors and entrepreneurs, or “business immigrants,” using a simple but highly attractive enticement: a Canadian passport. Under a new federal program, enacted partly to assist Vancouver, foreign nationals with a net worth of about 800,000 Canadian dollars ($600,000) would be fast-tracked for permanent Canadian residency if they agreed to loan half of that amount to the provincial government, interest-free, for five years. Students of Vancouver history might have relished the irony: In the early 20th century, Chinese migrants were forced to pay an openly racist federal “head” tax for the privilege of doing hard labor in the region’s mines, forests, and railroads. Half a century later, mainland Chinese were being courted for their business prowess and intellect (and bank accounts). But such is progress: With the Pacific Rim strategy, Vancouver wasn’t merely confronting the prejudices of its past, but openly acknowledging the vital role that diversity would play in its future. And by focusing on business immigrants, who would bring talent and capital, as well as their personal connections in China, says Yan, Vancouver believed it could become a dominant global hub—”the new Venice.”

This vaulting ambition perfectly captured the emerging ideology of the early 1980s. In the era of Reagan and Thatcher, the high-net-worth business immigrant was seen as a critical agent of economic globalization—the “trophy acquisition in neoliberal policy regimes,” as David Ley, an urban geographer at the University of British Columbia, has written. Eventually, more than 30 countries offered business immigrant programs; America’s, known as EB-5, was launched in 1990 and is widely deployed by real estate developers, including President Donald Trump and his son-in-law Jared Kushner. (The Kushner family’s use of the EB-5 prompted a flurry of headlines this weekend, after it was revealed that Jared’s sister, Nicole Myer, promised Chinese investors gathered at a Beijing hotel that they would get a “golden visa” if they invested in a luxury apartment complex in Jersey City that the Kushners are developing. According to Forbes, the Kushners have already used the program to channel $50 million to that project before Jared partially divested himself from the family business. But ethics watchdogs raised alarm at the fact that the pitch also took note of the Kushner’s “celebrity status,” and that Trump signed a spending bill that had an extension of EB-5 program tucked inside it the day before Myer made her pitch, and that investors were urged to act now before the rules change. The Kushner Companies have since told the Washington Post, which broke the story, that it “apologizes if that mention of her brother was in any way interpreted as an attempt to lure investors. That was not Ms. Meyer’s intention.”)

But the Canadian variant was far and away the most popular, thanks to both Canada’s historic Commonwealth ties to Asia and Asia’s suddenly unstable politics. With Hong Kong reverting to mainland Chinese rule in 1997, and with Beijing stepping up reunification pressure on Taiwan, anxious elites in both these enclaves looked to Vancouver as the perfect refuge for themselves and their capital. Of the 330,000 business immigrants who had used Canada’s visa program by 2001, more than a third of them, including most of the so-called millionaire migrants, settled in Vancouver. The volume of arriving wealth was astonishing. During a single three-week period in 1992, 50 millionaires opened accounts at a branch of HSBC in Vancouver’s Chinatown. In 1995, more than $500 million was wired from Hong Kong to banks in British Columbia. All told, Ley estimates that from 1988 to 1997, Vancouver gained $50 billion in immigrant riches. According to some reports, it was the spending habits of this new cohort that largely spared Vancouver from the deep national recession of the 1990s—an astonishing comeback for the Detroit of the Pacific.

Yet it wasn’t long before Vancouver’s new fortunes were looking distinctly Faustian. The initial belief that the newcomers would put their entrepreneurial skills to work in the local economy turned out to be embarrassingly naive. Although many of the first wave of business immigrants, from Hong Kong and Taiwan, had fully intended to start or invest in Vancouver businesses, few found much success, says Ley. Despite sharing a dialect with Vancouver’s ethnic Chinese (most of whom had come generations earlier from Hong Kong), new arrivals were often flummoxed by Canada’s business culture and its regulations and high taxes.

Entrepreneurial success was even more elusive for later arrivals. By the early 2000s, the business immigrant stream had shifted from Hong Kongers and Taiwanese to mainland Chinese, who, while wealthier than their predecessors, typically spoke neither English nor the Cantonese dialect favored in Vancouver’s Chinatown. Canadian authorities, meanwhile, did surprisingly little to help these newcomers assimilate. There were almost no government-sponsored English language programs, says Yan, nor was there any formal process for recognizing immigrants’ academic or professional credentials. And the city’s existing ethnic Chinese community was hardly welcoming. Beyond the differences in language, Ley says, locals were often put off by newcomers’ politics and lifestyle, not least their propensity for “showy wealth.”

Frustrated, some returned to China. (Today, about 300,000 Canadian passport holders reside in Hong Kong.) Others kept their Vancouver homes but “commuted” to China for work—a practice captured in a saying, “Hong Kong for making money, Canada for quality of life.” But many newcomers simply adapted by looking for a simpler kind of business to get into, says David Eby, a member of the opposition New Democratic Party (NDP) who represents Vancouver in the provincial assembly. And what they found, Eby says, “was, basically, real estate.”

This, too, shouldn’t have been a surprise. Beyond its attractive climate, pristine environment, and picture-book setting of coasts and snow-capped peaks, Vancouver was a real estate bargain. By the 1990s, the local housing market was recovering (thanks partly to so many wealthy new residents), yet home prices were still quite low, relative to other North American markets. Housing, in other words, represented a secure, comparatively liquid investment with ample potential for long-term price appreciation—”exactly the sort of asset you’re looking for if you’re looking to hide cash or just get to safety,” says Thomas Davidoff, director of the Center for Urban Economics and Real Estate at the University of British Columbia. Housing, adds Yan, had become “capital storage.”

The only problem is that a midsize housing market like Vancouver’s was unprepared for so much new capital. As Chinese money poured in, housing prices quickly outpaced local incomes, which remained among the lowest of any major Canadian metro area. Instead of building a gleaming new economy of technology and entrepreneurship, Vancouver found itself with a financialized economy, whose fastest-growing sectors were real estate, home construction, mortgage lending, and, eventually, speculation—and not just by foreigners. Locals, too, were now investing in the hot housing market.

Fueled by steadily more offshore capital, the city began morphing almost in real time. As lots became far more valuable than the often modest homes atop them, thousands of older homes were knocked down and replaced by mansions. In the city’s venerable business districts, block after block was razed for condo towers, whose units sat empty for months. Mom and pop stores gave way to high-end boutiques and luxury car dealerships. Residents’ complaints were largely ignored. Instead, in 2010, the Canadian government literally doubled down on business immigrants: Program applicants would now need a net worth of CA$1.6 million and be willing to lend the government CA$800,000. Foreign investors were undeterred by the hike. Chinese capital continued to flow into the Vancouver housing market, which, following a modest pause during the Great Recession, quickly resumed its meteoric ascent.

Vancouver, says Yan, was now captured by what economists call “path dependency.” The pattern occurs when a single business activity becomes so dominant locally that it forces adaptations in the regional economy, which then enable the dominant activity to become ever more powerful. “Everything in metropolitan Vancouver became involved in residential real estate,” Yan says. “And even other types of economic activities became ancillary to or dependent on residential real estate.” In neighborhood after neighborhood, the city’s middle-class character was giving way to something more like an upscale resort town—hardly a surprise for a place that one estimate says could be home to more than 100,000 Chinese millionaires. Working- and middle-class families, meanwhile, were leaving the metro area in such numbers that primary schools were shuttered.

Finally, in 2014, the Canadian government ended the business immigration program, turning away a backlog of more than 59,000 applicants. But a characteristic of path dependency is momentum: Once a local economy starts down such a path, Yan says, it’s very hard to stop. “You just go faster and faster.” Vancouver’s housing crisis had essentially become self-sustaining. In 2016, the region’s housing price-to-income ratio, a key measure of affordability, exceeded 11-to-1, making Vancouver the third least affordable city in the world. Or as Eby, the NDP legislator, puts it, Vancouver was on its way to becoming a “new Monaco.”

In such brutal economic circumstances, social tensions were inevitable. A city known for its international, multicultural character is now struggling to assimilate new immigrants who in many ways have kept to themselves. In some upper-end neighborhoods, businesses no longer bother posting signage in English—a trend that some longtime residents have tried to outlaw. Traditional social structures are shifting: Yan and Ley, for example, have found that many Chinese newcomers fall into a pattern known as the “astronaut family“: the wife and children live in Vancouver while the husband lives and works in China, his Canadian passport ever at the ready.

But the biggest source of cultural friction is the newcomers’ unprecedented spending power, as merely “showy wealth” has given way to surreal displays of conspicuous consumption. Accounts of sprawling, multimillion-dollar mansions, supercar driving clubs, and free-spending Chinese trust-fund babies have filled the local papers and drawn the scorn of the international press. “Chinese Scions’ Song: My Daddy’s Rich and My Lamborghini’s Good-Looking,” reads the headline of a 2016 New York Times piece detailing the extravagance of Vancouver’s fuerdai, the Chinese term for “rich second generation.” “They don’t work,” David Dai, founder of a supercar driving club whose members are 90 percent Chinese nationals, told the Times. “They just spend their parents’ money.” Adds Shi Yi, the owner of a supercar dealership, “In Vancouver, there are lots of kids of corrupt Chinese officials. Here, they can flaunt their money.” Perhaps predictably, there’s even an online reality show, Ultra Rich Asian Girls, which follows the daughters of Vancouver’s immigrant elites as they shop, eat, and party their way across the city’s high-end landscape. And yet, despite the labels, there is little about these antics that is particularly Chinese or even “foreign.” Ordinary people have always had to tolerate the upper set’s excesses and its blithe disinterest in local norms. It’s just that, until fairly recently, the upper set was usually white.

So it can be tempting to paint the Vancouver story as one driven primarily by white anxiety over the decline of what used to be the dominant culture. More than 5,000 British Columbians have signed a federal legislative petition that Starchuk launched last year to eliminate automatic “birthright citizenship” for children born in Canada to non-Canadian mothers. Predictably, this has provoked angry responses by progressives and raised fundamental questions about what it means to be Canadian—especially awkward given that the country’s English and French blocs have only recently come to uneasy terms over how to best accommodate different languages and cultures.

And yet, some of the bitterest complaints about Vancouver’s housing crisis come from second- and third-generation Chinese immigrants, who are no less hurt by rising real estate prices than their non-Asian neighbors. The Conservative member of Parliament sponsoring Starchuk’s birthright citizenship petition is Alice Wong, who came from Hong Kong in 1980. Gary Liu, a 38-year-old energy scientist whose family immigrated from Taiwan in 1993, says he and his wife have been trying to trade their small suburban apartment for a townhouse since 2014. “But every open house is always jam-packed with people from mainland China,” says Liu, who now moonlights as a housing advocate. “And when we ask where they’re from, it’s, ‘Oh, from Shandong Province.’ ‘From the inland provinces.’ They are just here to buy a house.”

But for Vancouver’s shell-shocked middle class, the most infuriating piece of this entire narrative was the government’s unwillingness to acknowledge the problem. In press interviews, lawmakers systematically dismissed suggestions that foreign capital was fueling the housing crisis. Instead, they blamed skyrocketing prices largely on the constrained housing supply and lack of urban density—a familiar argument that might carry more weight (Vancouverites do like their single-family homes) were it not for the soaring rates of unoccupied homes and condos.

Some of this denial was financially driven. Provincial and city governments have benefited hugely from business immigrants’ interest-free loans and from the surge in real estate transaction taxes (more than $1.5 billion to British Columbia in 2016 alone). Politicians became accustomed to the largesse of the bloated real estate sector, whose campaign contributions have been running roughly twice those of the two next largest sectors, mining and forestry. In recent years, lawmakers and developers hardly attempted to conceal their connections: Before stepping down this year, Bob “Condo King” Rennie, one of Vancouver’s largest real estate players, was the chief fundraiser for the ruling Liberal Party, which over the last decade took in 35 times as much in contributions from the real estate sector ($10.5 million) as did the opposition NDP ($300,000).

But there was also a subtler dynamic at work: Political institutions, too, are warped as an economy becomes path-dependent. This was the pattern in Phoenix, where firms lured to the city eventually came to dominate local politics and began demanding—and steadily winning—more tax breaks and other enticements. It was also the story in the San Francisco Bay Area, where governments have sweetened the pot with a “Twitter tax break,” say, or by permitting tech firms’ luxury employee buses to use public transit stops.

This co-opting dynamic often brings serious social costs, such as underfunded schools, infrastructure, and other public services. Yet the optics are deceptive: The more fiercely that cities compete for economic growth and the capital needed to fuel it, the more their political cultures justify these costs as essential for prosperity—and, indeed, the more these costs come to be seen as affirmations of that prosperity.

That dynamic was clearly at work in Vancouver. Time and again, the political class simply refused to acknowledge that the Pacific Rim capital intended to fuel a new entrepreneurial prosperity was instead merely inflating a massive housing bubble. Complaints about foreign investment were dismissed as xenophobic. Early calls for policy action—for example, a city tax to penalize buyers who left their homes vacant—were resisted for years. (Vancouver only just enacted a 1 percent vacancy tax in late 2016.) To be sure, officials faced numerous constraints. Cities’ taxing powers are heavily controlled by the province: For example, when Gregor Robertson, Vancouver’s NDP mayor, asked provincial lawmakers for a tax on real estate speculators in 2015, he was rebuffed by ruling Liberals. And local leaders are navigating a complicated cultural minefield as they try to assuage concerns over affordability without offending Chinese Canadian voters.

But Robertson and other city leaders also heavily courted Chinese investment and continue to blame the housing crisis on a lack of supply—a position that sidesteps the region’s large number of empty foreign-owned homes. And they haven’t been above exploiting cultural tensions. When Yan published data indicating that buyers with Chinese surnames accounted for two-thirds of all Vancouver-area homes sold between August 2014 and February 2015 (and for 91 percent of homes priced at $3 million or above), his research was attacked by industry and government officials as racist. (Robertson and other city officials declined to comment for this story.)

The degree to which the hedge-city dynamic has warped the political system can still be hard to fathom. Even as late as June 2016, as single-family housing prices were posting a one-year gain of some 40 percent, British Columbia Premier Christy Clark took local real estate companies with her on a trade mission to Asia. The government also ignored reports that Vancouver real estate was being used to launder some of the estimated $2 trillion in corrupt wealth that has fled China since the 1990s. It was only after a new government reporting system showed that foreign ownership in parts of Vancouver was much higher than previously claimed—and after polls showed affordability as the top issue in the 2017 provincial elections—that Clark’s Liberal Party agreed to the 15 percent tax on foreign real estate purchases.

That tax did bring some relief. Sales volumes toppled, and even the city’s normally Pollyannaish real estate industry now predicts a nearly 8 percent drop in home prices in 2017. But as the NDP’s Eby points out, Vancouver’s housing market is so inflated that restoring affordability would require a price correction of 40 percent, which would devastate those “who leveraged themselves many times over to try to get in the market.”

Such a dire outcome is hardly certain. But the market has unquestionably shifted. Many big developers who raced to build condos in Vancouver have turned their attention south to Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Sellers of upper-end homes have been forced to cut prices dramatically. In China, meanwhile, Vancouver mania is cooling. Three years ago, Vancouver was the third most desirable city worldwide for wealthy Chinese immigrants, behind only Los Angeles and San Francisco, according to the Hurun Research Institute. By 2016, Vancouver had fallen to sixth. After years of anxiety that foreign investment was making their city unaffordable, some Vancouverites now fear the opposite threat—that departing foreign capital might crater the housing market and cause a recession. “We face a really difficult moment here, because this was allowed to carry on for so long,” Eby told me. “If there is a lesson for other jurisdictions here, it’s identify this [trend] early and don’t wait to take action.”

It would be easy for other cities watching Vancouver to misread the crisis as somehow unique and unrepeatable—a perfect storm of exceptional political and historical factors. But if current trends continue, over the next decade the 1 percenters of emerging economies will continue to move trillions of dollars overseas. And while that capital will flow into every conceivable asset—from oil companies to vineyards to art—real estate will be a priority. In an era of low interest rates, sluggish economic growth, and rising political uncertainty, rapidly appreciating real estate in stable Western countries offers wealthy hedgers an increasingly rare opportunity for profits and safety. In mainland China alone, there are more than 1 million households with a net worth in excess of $1.5 million, according to the Hurun Research Institute, and three-fifths of them want to buy property overseas in the next three years. The real estate consultancy Juwai estimates that Chinese real estate holdings abroad, which totaled $80 billion in 2015, are expected to balloon to $220 billion by 2020. Beijing is trying to staunch the outflow of capital, with new regulations on currency transfers and a tough anti-corruption campaign coordinated with Western governments. But “the capital is still getting out,” says Dean Jones, head of the Seattle office of Realogics Sotheby’s International Realty, a global real estate firm that focuses heavily on Asian buyers. “And a lot of the capital is already out. And those resources are living in plenty of bank accounts and plenty of houses and plenty of art galleries around the world.”

When hedgers move those assets into real estate, the buys will be widely dispersed. Hong Kong, Sydney, and London are already known as hedge cities—but new candidates are always trending: Chinese investors plan to spend $100 billion building a massive luxury “city” on the outskirts of Singapore. But American cities remain a top target—between 2011 and 2015, Chinese purchases of US real estate more than tripled to $27.3 billion, according to the National Association of Realtors, and they now account for more than a quarter of total proceeds from all foreign purchases, or more than four times the amount from the next largest group of purchasers, Canadians. Urban real estate in the United States is rapidly appreciating but remains a bargain relative to many emerging-market cities. And although the US government doesn’t recruit foreign capital quite as aggressively as Canada did, our EB-5 program grants residency to foreigners who invest $1 million in commercial projects.

Many American cities feel they have little choice but to woo foreign residents. Despite huge demand for infrastructure and services, cities are under intense pressure to retain local employers by providing them with tax cuts, and the temptation to fill the shortfall with foreign hedgers is powerful.

Chinese hedgers aren’t the only ones eyeing American real estate. Russian and Middle Eastern investors are heading for Eastern cities like New York and Washington. South American elites are buying in Miami and Houston. But Chinese house hunters arguably have the greatest impact, thanks both to the scale of their collective wealth and to their preference for midsize West Coast cities.

Exhibit A is Seattle, which last year replaced Vancouver as the third most desirable city for wealthy Chinese immigrants. Realogics Sotheby’s estimates that half of its Seattle-area suburban home sales in 2016 involved Chinese buyers—up from 30 percent in 2015. Some of that increase reflects cooling interest in Vancouver. But it also reflects a recognition that this booming city has what it takes to be the next hedge city: an attractive setting, good schools, a diverse, tolerant culture—and, of course, a real estate market that, despite soaring prices, remains undervalued relative to urban China. On a deeper level, Seattle’s rising star illustrates the whack-a-mole nature of global capital. A city may deter foreign investors, but that only means they will flow into new cities. “This is Vancouver 2.0,” Jones, head of the Realogics Sotheby’s Seattle office, told Bloomberg last fall. “A lot of the same motivations and goals are being replicated in Seattle.”

Seattle isn’t in Vancouver territory yet; its economy is far more diverse and robust, and thus less sensitive to foreign capital’s destabilizing effects. But already there are Vancouverlike symptoms, including flipping by nonresident players and a rising number of empty homes, especially in high-end neighborhoods. “About a third of my buyers don’t live here,” says one Seattle-area realtor who deals exclusively with mainland Chinese buyers. “They come here maybe a couple of months a year, or not at all. But they don’t want to rent their property.” At a time when Seattle is considering spending heavily on affordable housing, that trend is disconcerting. “We’ve got a housing shortage right now,” says Seattle Councilman Mike O’Brien. “And the idea that folks would park their capital in housing but not use [it] is not anything we want to see.”

Yet Seattle has even fewer defensive options than Vancouver. Seattle could target speculative practices that aren’t specifically foreign—a penalty on vacant homes, for example. But state law won’t allow for a tax on foreign buyers—and talk of such a policy has raised hackles among Seattle’s many ethnic communities. Further, whereas Canada has suspended most of its business immigrant programs, America’s EB-5 program, a favorite of President Trump, despite his anti-immigrant rhetoric, is expected to remain in place.

More fundamentally, any barrier that Seattle or other US cities might plausibly erect would simply be too modest. For starters, global investors can always get around taxes or other obstacles, via shell companies and local partnerships. And for a determined hedger fleeing political repression or economic turmoil (China is jailing corrupt tycoons and its stock market has fallen nearly 40 percent since 2015), even a 15 percent tax is just the price of doing business. And while upward of 40 percent of all housing in Hong Kong and Singapore is publicly owned, and thus truly insulated from foreign capital, that is a political nonstarter for US cities.

But the larger obstacle is that a lot of people in Seattle want more foreign capital, not less. Local developers have worked hard to court offshore investment, and real estate firms have reconfigured themselves to embrace an elite Chinese clientele, with Mandarin-speaking agents and brokers who act sort of like concierges. Wenjun Chen, a Seattle-area realtor, not only translates for her Chinese clients, but often runs their errands, takes them shopping, makes social introductions, and teaches the basics of single-family house maintenance. “A lot of them are so helpless,” Chen told me.

Back in Richmond, Kerry Starchuk is experiencing a different sort of helplessness. Her own grown children cannot afford to live in the town where they were raised. Her neighborhood continues to feel like a cross between a ghost town and a war zone. Construction noise is constant. On virtually every block, homes are still being either built or torn down. “To see my neighborhood go the way it has and then not have the support from the politicians,” Starchuk says, “even though they know what is going on…”

She trails off. We’re stuck in traffic in Richmond’s downtown, where half the storefronts seem to be bank branches or brokerages. New condos and construction cranes loom overhead. Dozens of signs, many only in Chinese, announce future projects. Last year, a local realtor named Steve Saretsky released figures showing that almost half the condo units sold in downtown Richmond during the first nine months of 2016 in buildings at least a year old had never been occupied. When Starchuk drives down here at night, she says, many of the completed buildings are dark. “I don’t get this,” she says. “Are they just letting the market do its own thing? It’s a free-for-all.”

The 15 percent tax prompted some foreign investors to leave for Seattle or Toronto (the new favorite among Chinese buyers searching for Canadian real estate). But others have simply shifted into new asset classes in Vancouver. Last year, Chinese investors began snapping up farm acreage just outside the city to build mansions and resorts, and in recent months they’ve waded into Vancouver’s industrial property markets. The University of British Columbia’s Andy Yan has found that prices for land zoned for light industrial companies jumped 48 percent in a single year—a trend that will make it even harder for Vancouver to court the startups and other businesses that might help prod the city from its real estate path dependency.

All told, many longtime residents here feel used—by a global elite, but also by a shortsighted government so eager to court that elite that it continues to put the region’s long-term prosperity at risk. Such complicity may prove politically costly. Polls show the ruling Liberal Party neck and neck with the NDP for provincial elections in May. Yet at this late date, it’s hard to see what even fresh leadership can realistically do to change the city’s narrative. Even if the government can devise a mix of taxes, regulations, and other market nudges that somehow, miraculously, cool the economy without causing a recession, the overwhelming consensus here is that the harm already inflicted will take years to heal. “When it comes to the housing market, we’re a burned-over region,” says Ley, the University of British Columbia urban geographer. “The damage here is so great, it’s hard to see how we get out of this hole.”