David J. Phillip/AP

Two weeks after the presidential election, white nationalist Richard Spencer held forth on a cable news show about how white people built America. “White people ultimately don’t need other races in order to succeed,” he told the audience of the black-oriented program, NewsOne Now.

The exchange grew heated as host Roland Martin questioned Spencer’s rhetoric: Didn’t slaves help build America? Wasn’t the nation’s 19th-century economic boom propelled by the slave labor that produced the world’s cotton on Southern plantations?

America’s rise was “not through black people” and “has nothing to do with slavery,” Spencer retorted. “White people could have figured out another way to pick cotton,” he said. “We do it now.”

He is in a position to know. Spencer, along with his mother and sister, are absentee landlords of 5,200 acres of cotton and corn fields in an impoverished, largely African American region of Louisiana, according to records examined by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting. The farms, controlled by multiple family-owned businesses, are worth millions: A 1,600-acre parcel sold for $4.3 million in 2012.

The Spencer family’s farms are also subsidized by the federal government. From 2008 through 2015, the Spencers received $2 million in US farm subsidy payments, according to federal data.

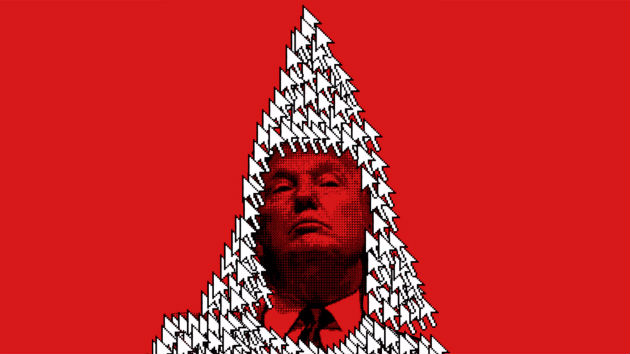

Although Spencer has attracted extensive media attention as a leader of the so-called alt-right movement—particularly after he drew Nazi salutes at an event celebrating Donald Trump’s election—he has never explained publicly how he supports himself while actively promoting his agenda via conferences and media appearances. The finances of his nonprofit think tank, the National Policy Institute, are a mystery; the organization hasn’t filed a public report since 2013. On Monday, the Los Angeles Times reported that the IRS revoked the institute’s tax-exempt status.

Spencer, 38, is a dropout from a Duke University Ph.D. history program who emerged during the Trump campaign as one of the nation’s most visible white separatist agitators. In his writing, speeches, and interviews, he has given an intellectualized explanation for how he came to advocate creating a whites-only “ethno state” in North America. While in graduate school, he has said, he was compelled by critiques of multiculturalism and political correctness and by demographic data indicating that whites are en route to minority status in the United States.

But the Spencer family’s business interests and geographic history suggest a different possible lineage for Richard Spencer’s racist politics. The family’s farm holdings are a legacy of its ties to the Jim Crow South, passed down by Spencer’s grandfather, who built the business during the turbulent civil rights era.

Spencer declined in an interview this week to discuss how much money he personally receives from cotton farming and government subsidies, and whether that income funds his political activities.

“I’m not involved in any direct day-to-day running of the business,” he said, later adding, “I’m going to navigate the world as it is, and I’m not going to be a pauper.”

One Spencer family farming company, which holds title to 400 acres of land, is called the Poor Richard Partnership.

In the interview, Spencer also downplayed his family’s influence on his political views, saying, “My parents are very mainstream Episcopalian Republicans in Dallas.”

Although Spencer grew up in an affluent neighborhood of Dallas and now splits his time between Montana and Washington, DC, his family lived in the South for generations. Records show his mother attended segregated schools as a girl in the small northeast Louisiana city of Monroe. Later, Spencer’s mother inherited farms in northeast Louisiana from her late father. Today, her two children are her business partners.

Spencer’s mother did not respond to an email and voicemails seeking comment for this story. In the past, she has said she does not share her son’s views. In an open letter sent to their local newspaper in December, Spencer’s parents, Sherry and Rand, said that while they love their son, “we are not racists. We have never been racists. We do not endorse the idea of white nationalism.”

The region that is home to the Spencers’ farms has a history of slavery and racism. Through the civil rights era, the Ku Klux Klan targeted black residents there with lynchings, cross burnings, and other violence. In Tensas Parish, where the Spencers own 3,000 acres of farmland, blacks didn’t win the right to vote until 1964, according to Elvadus Fields Jr., mayor of the town of St. Joseph.

Agribusiness in the region today is heavily mechanized and provides few jobs. In 2013, CNN reported that East Carroll Parish—where the Spencers own 900 acres of farmland—suffered from the worst income inequality in the nation. The richest 5 percent of residents earned an average of $611,000 per year, 90 times what the poorest 20 percent earned. The parish’s population is 67 percent black.

Race relations have improved significantly in recent decades. But after Trump’s election, some white residents celebrated by draping their pickup trucks with Confederate flags and driving through the region’s towns, according to the Reverend Roosevelt Grant, head of the NAACP branch in Winnsboro, Franklin Parish, near another of the Spencers’ farms. The Trump presidency, he says, “has caused people to pray more.”

Spencer’s maternal grandfather, Dr. R.W. Dickenhorst, established the family farming business. He was a radiologist who started a medical practice in Monroe in 1952 and became wealthy and socially prominent, according to local newspaper obituaries. Racial segregation was a given in Monroe then. Blacks were barred from housing, schools, and public facilities used by whites. White superiority “was the way of life; that was the way it was, and anyone challenging it was challenging God’s will,” says the Reverend Roosevelt Wright Jr., a local historian in Monroe.

Dickenhorst’s daughter, Sherry, who would grow up to be Richard Spencer’s mother, enrolled in the all-white Neville High School in 1962, according to district records. In 1964, at the start of her junior year, integration of the school began, with a single African American student enrolling. As Dickenhorst’s medical practice prospered, he bought farmland in northeast Louisiana on the Mississippi River’s west bank. He died decades later, in 2002, and his wife died the following year. By then, their only daughter was the wife of a wealthy Dallas eye surgeon and the mother of two grown children: Richard Spencer and his sister. (Spencer’s sister did not respond to an email and phone calls seeking comment.)

Today, through Dickenhorst Farms and several related companies, Sherry Spencer, 68, and her two children jointly own most of the family farmland, according to federal data compiled by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group. Sherry is a general partner in Dickenhorst Farms, and Richard and his sister are part owners, according to state and federal records. The family contracts out crop production to local farmers, a common practice in a region where corporations and absentee owners control much of the land.

The Spencer family’s farms are headquartered at a $3 million home in the ski town of Whitefish, Montana, where Sherry Spencer now lives. Also headquartered there: Richard Spencer’s think tank, his AltRight.com website, and other white-nationalist-related enterprises he controls, including a book publisher and a web design outfit. Spencer also has lived in Whitefish in recent years—sometimes in his mother’s home, and sometimes in a condominium she owns, according to documents and interviews.

The Spencers have received payments from two federal farm programs. One is the commodity subsidy program, intended to guarantee income for farmers who are helping to maintain supplies of certain crops deemed important by the government. The other is the conservation reserve program, which pays farmers for environmentally sound farming practices. Most of the $2 million paid to the Spencers has been in commodity subsidy payments for growing cotton.

Yet, Spencer has been bitterly critical of America and its government.

“This is a sick, disgusting society,” he declared in his speech at an alt-right gathering in Washington after the election, “run by the corrupt, defended by hysterics, drunk on self-hatred and degeneracy.”

Reveal producer Emily Harris, Reveal host Al Letson, and freelance reporters Jade Williamson and Vladimir Jakovljevic contributed to this story.