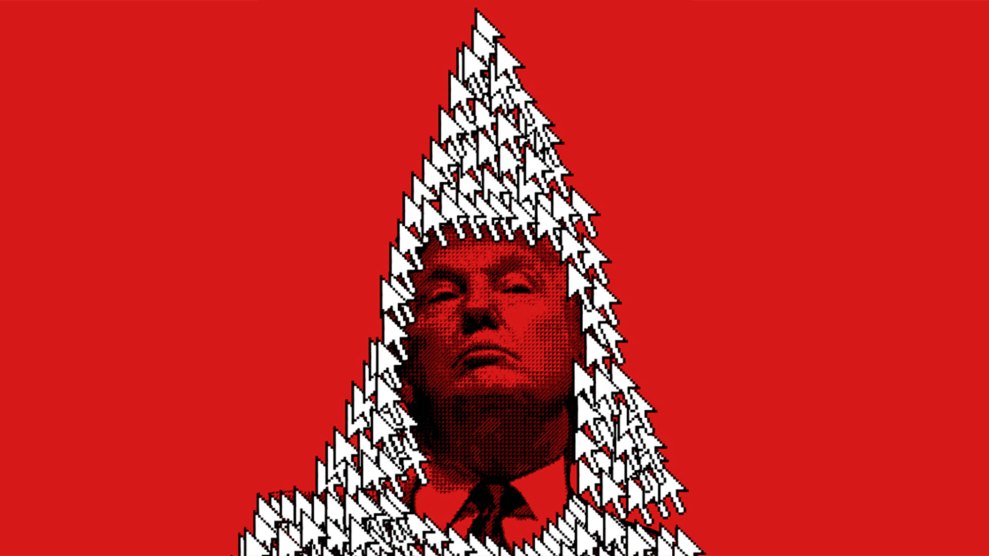

Justin Renteria

There has been fierce debate in recent weeks over how the media should refer to a loose-knit movement of far-right extremist groups that gained prominence with the election of Donald Trump. Is the so-called alt-right made up of white nationalists? White supremacists? Neo-Nazis? Bigoted nativists? (The answer is, all of the above and more.) And is “alt-right” an acceptable term, or is it just vaguely cool-sounding code for age-old forms of virulent racism and anti-Semitism?

In November, ThinkProgress announced that it would no longer use the term alt-right, calling it a public-relations tool for racists. The Associated Press and the New York Times recently issued guidelines for use of the label, suggesting that it appear as “so-called alt-right” and be accompanied by a description of its meaning. (Mother Jones has used that approach for several months.) There can be zero doubt that the broader movement, such as it is, draws on hateful far-right ideologies, as I’ve documented through months of in-depth reporting. And particularly in the wake of an alt-right celebration of Trump’s victory that waxed full Nazi, use of the term has remained a flash point.

To shed further light on the politics of hate in the Trump era, I interviewed two researchers from top organizations in the United States that study and track hate groups: Heidi Beirich, the director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project, and Marilyn Mayo, a research fellow with the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism. Here is how each defined racism, white supremacy, the alt-right, and other terms, followed below by some further analysis from two academic experts:

Racist

- Someone who believes that a particular race is superior to another. Usually racists are racist against black people or people of color (in the United States). (Southern Poverty Law Center)

- Someone who makes negative judgments or assumptions or embraces negative stereotypes about others based on their perceived racial or ethnic background. (Anti-Defamation League)

Bigot

- Someone who doesn’t tolerate people of different races or religions. Bigots are what we usually refer to as “garden variety” racists. (SPLC)

- Similar to a racist; someone who targets not only people of different races or ethnicities, but also people of other national backgrounds, sexual orientations, genders, or religions. (ADL)

White supremacist

- Someone who believes that the white race is inherently superior to other races, and that white people should have control over people of other races. This usually means the idea that whites should control government power. In certain cases, white supremacists also advocate ethnic cleansing and an all-white state. (SPLC)

- A term used to characterize various belief systems central to which are one or more of these tenets: (1) whites should have dominance over people of other backgrounds, especially where they may co-exist; (2) whites should live by themselves in a whites-only society; (3) white people have their own “culture” that is superior to other cultures; (4) white people are genetically superior to other people. As a full-fledged ideology, white supremacy is far more encompassing than simple racism or bigotry. (ADL)

White nationalist

- A person of white European decent who believes in a white nation for and run by whites. White nationalists believe race and IQ are related and that black people are inherently inferior in IQ. There is a dispute among white nationalists about whether Jews are an enemy to white people or are actually as white as any European. (SPLC)

- A term used by white supremacists as a euphemism for white supremacy. Some white supremacists try to distinguish it further by using it to refer to a form of white supremacy that emphasizes defining a country or region by white racial identity and which seeks to promote the interests of whites exclusively, typically at the expense of people of other backgrounds. (ADL)

Alt-right

- A recent rebranding of white nationalism. (SPLC)

- The alt-right—short for “alternative right”—is a loose network of people who promote white identity and reject mainstream conservatism in favor of politics that embrace implicit or explicit racism, anti-Semitism and white supremacy. Many in the alt-right seek to inject racism and anti-Semitism into the conservative movement in the United States. (ADL)

Neo-Nazi

- Pertains to a person or group holding political views associated with or derived from those of Adolf Hitler and Nazism. Anti-Semitism is at the core of this belief system, as it was for Hitler. (SPLC)

- Neo-Nazi is a term used to refer to members of various groups and movements around the world in the post-World War II era that have attempted to revive key principles of National Socialism and/or that have significantly appropriated the trappings, symbology, and mythology of the Third Reich. (ADL)

It bears noting that the SPLC and the ADL are not merely organizations that observe hate groups; their choices of words reflect both a deep knowledge of their subjects and a desire to counteract them. Is white nationalism a legitimately distinct category, as the SPLC suggests, or is it just a softer sell of white supremacy, as the ADL argues? I put that and other questions about these definitions to two academics: Lawrence Rosenthal, the chair of the University of California-Berkeley Center for Right Wing Studies, and Michael Waltman, a University of North Carolina communication professor and expert on white supremacist groups.

Rosenthal says the term “white nationalist” indeed carries a distinct meaning: White nationalists want to be apart from other races but do not necessarily claim to be superior. White supremacy, on the other hand, claims that whites are better than other races and “need to dominate.”

But UNC’s Waltman agrees with the ADL that “white nationalist” is essentially a propaganda tool. The first time he saw it used was in 1994, he says, by former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard Tom Metzger. The Klan had begun to recognize that the word ‘white supremacist’ was associated in people’s minds with “a certain kind of uncultured bigot,” Waltman says. “They tried to run away from that term in many ways by using the term ‘white nationalist.'”

“It is really hard to be a white nationalist and not sort of think of white people as better than other folks,” Waltman adds. “That is why [they] want America to be a white country. But to simply equate the two and never talk about white nationalism is to ignore the strategic purposes for which that term was introduced.”

As an apparent confluence of extremist groups galvanized by Trump over the past year, the alt-right may be even trickier to define. UC Berkeley’s Rosenthal explains the alt-right as “an internet-based, social media-based affinity group that covers a fairly wide spectrum,” ranging from populist nationalism to the realm of the KKK and neo-Nazis.

“The ADL has it right to emphasize that the alt-right really represents a broad network of people,” agrees Waltman, including so-called men’s rights activists, for example. But when it comes to the movement’s virulently racist and anti-Semitic core, he adds, “‘alt-right’ represents another rebranding—one with even more explicit political purposes to become part of the mainstream.”

What all of this means in terms of how we talk and write about these groups is a matter of perspective. As Vox‘s Jenée Desmond-Harris points out, the nuances between racist ideologies may matter much more to the people who ascribe to them than to those who would be the victims of the policies that they promote. It can seem like pointless quibbling to distinguish between white nationalists, white supremacists, and the alt-right when they all push bigotry and support policies such as racial profiling and race-based deportations that would be deeply hurtful to religious groups and people of color.

Yet journalists, academics, and watchdog organizations will likely continue using all these terms and more to describe the far-right extremists who’ve ridden Trump’s coattails. One imperative is to understand these groups as they understand themselves, whether to help inform the public or to counteract them. For journalists in particular there is also a strong tradition of using the names that people and organizations say they want to be known by—among other reasons, to protect themselves from accusations of bias (and from libel suits).

But in the media, we also have a duty to call out hype and deceit. With the so-called alt-right, that means being clear about its radical and profoundly disturbing core.