<a href="https://flic.kr/p/6Rm9ys">Kenn Wilson</a>/Flickr

One evening a few years ago, a wealthy former Wall Street banker and a convicted armed robber walked into a fancy club in Buffalo, New York—the fading industrial city that, oddly enough, has become America’s debt-collection capital. The banker, Aaron Siegel, and the ex-con, Brandon Wilson, were there to meet with Jake Halpern, a hometown boy turned New Yorker writer. Halpern wanted to know what was up with these strange bedfellows, and how they managed to recover a huge bundle of consumer debt—an Excel spreadsheet packed with debtor data that they’d dubbed “the package”—they believed had been stolen from them.

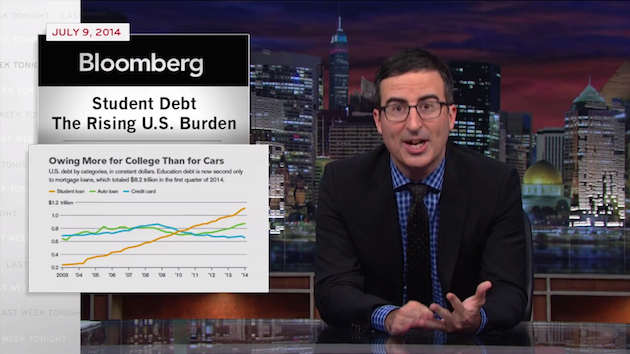

Halpern turned the tale into a book titled, Bad Paper: Chasing Debt From Wall Street to the Underworld. In the book, which published earlier this month, he follows how credit card balances, payday loans, even plastic-surgery debts, move down the food chain from the big banks to ever-smaller, ever-sketchier collection firms that scrap and claw to wring every last penny out of those in hock. I caught up with Halpern to talk about his adventures in this lawless realm. (I also asked him to provide some tips for people who are worried about debt collectors.)

Mother Jones: How did you get interested in this story?

Jake Halpern: My mother was being hounded by a debt collector over a debt that she didn’t owe, and she eventually just paid it because she wanted the calls to stop. I was very surprised. It sounded so strange. I started poking around on the internet and found this was extremely common. There was this world where these debts were sold off by the banks for pennies on the dollar and bought and sold.

I was really interested in the idea that these debts were out there in the form of Excel spreadsheets. I wrote up a brief pitch for the New Yorker and sent it over to my editor, Daniel Zalewski, and he wrote back and said “Remnick greenlighted it. When can you get us 5,000 words?” I had really puffed up my chest and said I was a Buffalo boy and could get all of these people to talk to me, and now I was on the hook. So I went back to Buffalo and no one would talk to me! Then I sent Facebook messages to everyone I knew in high school and everyone my brother knew in high school, asking who would let me in the door.

At the time, Brad Pitt’s production company wanted to turn this idea into an HBO show. So I set up all these interviews and there were all these people who didn’t want to speak with me for the magazine but were happy to talk for the TV show. Among them were Aaron Siegel and Brandon Wilson. As I heard them start to tell their story my eyes lit up. I spent the next year and a half trying to get those guys to cooperate. And that’s the genesis.

I hope [readers] just enjoy a rollicking good tale about a banker and an armed robber who become friends and go into business to track down this debt that’s stolen from them and takes them into the underworld of the buying and selling of debt. There’s an element of this story that felt like a Quentin Tarantino film, and that’s what drew me in. That was my concept from the beginning—a crazy caper that’s a parable for what happens in the absence of regulation.

MJ: It seems as though you really liked your main characters.

JH: The very first time I saw those guys interact, I knew that was a book. I was interested in this relationship between the armed robber and the banker who were from different worlds but had similar goals. It was kind of a metaphor for this larger marriage of the banks selling off their debt and these street guys scrapping over it.

They needed each other. Aaron needed Brandon for someone who could get good deals on paper and Brandon needed Aaron because he needed someone to be the respectable face of the operation. But they didn’t fully trust each other. Then there’s the personal dynamic. Aaron thinks it’s cool to be friends with an armed robber, and Brandon feels good that he’s being invited to Clinton fundraisers.

MJ: Your sources really opened up to you. I loved the scene in which Jimmy, an ex-con-turned-debt-collector, talks about his drug-dealing days and how, when he saw his heroin-addicted father for the last time, his gold chain dangled down and blocked his view of his passed-out father’s face. How did you get people to talk to you like that?

JH: There were a number of people who were just extremely candid. I don’t know. Sometimes I found myself mystified that they were so open. I think part of it was that no one ever asked them—there was no one there to witness their pain and their struggles, and it just kind of gushed out. I would just leave the recorder on and [Jimmy] would just talk. It’s almost easier to tell someone who’s so different from you.

MJ: I also enjoyed the scene in which a judge told you that you couldn’t use a court hearing in your book, and a lawyer for a creditor threatened to have you prosecuted for “practicing law without a license.” What was your reaction to that?

JH: I was genuinely spooked—even though I’m the son of a law professor and a journalist. Looking back, it seems so comical, or absurd. It wasn’t until two weeks later that I realized that that was probably one of the more important moments in the book.

MJ: I also loved the part about Tony Scott, who runs a buy-here-pay-here car lot in Georgia: You write, “Tony’s business model, I realized, existed at the rock bottom of the credit market. It was what existed in the complete absence of trust: a marketplace where creditors had lost faith in debtors and debtors had lost any sense of obligation—or ability—to pay….. With him, it was back to basics. There was a guy named Tony. He was your last resort. He charged you 24 percent interest, and, if you wanted a car, you paid it. If you didn’t pay, Tony took the car. And if you caused trouble, Tony made it known that he was only too happy to whip out his Ruger LCP .380 compact pistol and add some ventilation to your shirt.” Did you just trick me into reading a book about poverty?

JH: It’s difficult to write about poverty in a way that doesn’t feel clichéd. In one version of this book I started the book out with Joanna and Teresa, [two debtors listed in the stolen “package”], and my editor suggested I not do that, because as important as their stories were, they felt really familiar. I had to find a way to put the stories about poverty in there in a way that slipped them in—if it’s expected, you just kind of gloss over it.

When we were selling the proposal, we got a response back from a very reputable publishing house saying, “Basically this is a book about poor people, and poor people don’t buy books, so ‘No.'” The trick then becomes: How do you tell this story in a way that doesn’t turn people off before they’re really into it?

MJ: What policy changes could help improve debt collection in America?

JH: I think the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is on the right track. There are issues I point out in the book—they’re policing the largest companies, but there are something like 9,000 debt-collection companies in the US. I think that you need more policing on the state attorney general level. The CFPB’s budget is just 2 percent of what JPMorganChase set aside for litigation and fees for 2014.

One other huge problem is there’s no system in place for tracking who owns these debts. Imagine a system where there’s no chain of titles for cars, no VIN numbers, and no DMV. There’d be total chaos! But that’s basically the system for debt. There are signs it will continue to improve but it’s not fixed.

MJ: Anything else you think our readers should know?

JH: The guy that ended up with the stolen debt, I identify him simply as Bill. He didn’t want to talk to me at first, and then just before I finished writing the book, he talked to me at length, a three-hour taped interview. At the end of it, I asked him the same question you just asked me. And he said, “I just want to make it clear in no uncertain terms that when Brandon came down and visited my shop, he didn’t punk me off. I didn’t back down.” His main thing was he wanted to make sure that his tough-guy credentials were intact. I guess it made sense, but it just goes to show that you never know why someone will talk.