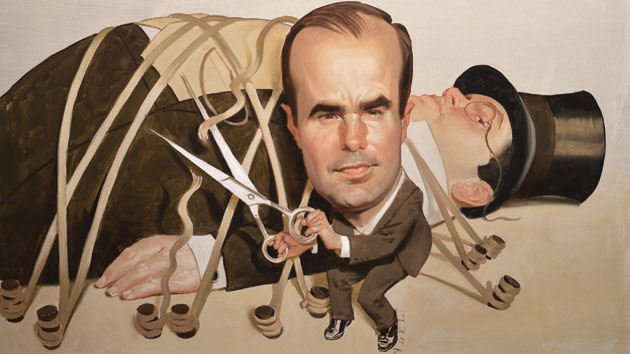

Illustration: Daniel Adel

Ambrose Bierce once quipped that a lawyer is one skilled in the circumvention of the law. By that definition, Eugene Scalia is a lawyer of extraordinary skill. In less than five years, the 50-year-old son of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has become a one-man scourge to the reformers who won a hard-fought battle to pass the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act to rein in the out-of-control financial sector. So far, he’s prevailed in three of the six suits he’s filed against the law, single-handedly slowing its rollout to a snail’s pace. As of May, a little more than half of the nearly four-year-old law’s rules had been finalized and another 25 percent hadn’t even been drafted. Much of that breathing room for Wall Street is thanks to Scalia, who has deployed a hyperliteral, almost absurdist series of procedural challenges to unnerve the bureaucrats charged with giving the legislation teeth.

Scalia has “created this sense that we’re paralyzed, because if we write a rule we’re just going to be reversed,” says Lisa Donner, executive director of the watchdog group Americans for Financial Reform. The threat of more suits, she says, has “cast a real chill” over Wall Street regulators, particularly at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Scalia’s legal challenges hinge on a simple, two-decade-old rule: Federal agencies monitoring financial markets must conduct a cost-benefit analysis whenever they write a new regulation. The idea is to weigh “efficiency, competition, and capital formation” so that businesses and investors can anticipate how their bottom line might be affected. Sounds reasonable. But by recognizing that the assumptions behind these hypothetical projections can be endlessly picked apart, Scalia has found a remarkably effective way to delay key parts of the law from going into effect.

Former Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.) says Scalia and the big banks are attempting an end run around the law he coauthored: “These are ideologues who want to kill the rules. They can’t say they’re unconstitutional. They are doing this because it’s the only possible way to knock them out.” (Scalia declined to comment for this article.)

Eugene, the second of Antonin and Maureen Scalia’s nine children, bears a passing resemblance to his father. Both are known for being congenial with colleagues across the partisan divide. But Gene lacks his father’s bombast and love of the limelight. And where Justice Scalia pens withering diatribes against liberalism from the bench, his son is in the trenches, waging a battle of attrition.

His legal career began in 1990, when he joined Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, whose roster of all-star conservative lawyers has included Whitewater-Lewinskygate special prosecutor Ken Starr and former solicitor general Ted Olson. Today, Scalia is a partner, though he does not share in any revenue from the firm’s cases before the Supreme Court (otherwise his dad might be pressured to recuse himself). He spent most of the ’90s focused on labor law, primarily opposing workplace safety rules for white-collar employees; columnist Molly Ivins dubbed him “the godfather of the anti-ergonomics movement.” He defended SeaWorld against federal safety rules implemented after an orca killed a trainer during a live show in 2010. (Scalia has argued in court that the company has no more responsibility to protect its trainers than the NFL has a duty to combat on-the-field injuries.)

In 2001, President George W. Bush tapped Scalia to work as the Department of Labor’s solicitor. “It was the classic fox in the henhouse situation,” says Lynn Rhinehart, general counsel at the AFL-CIO. When Senate Democrats blocked his confirmation, his father perceived a deeper slight. “Gene, I’m sure, didn’t get his appointment as solicitor of labor in part because of his name,” Antonin Scalia told his biographer, Joan Biskupic. In the end, Bush bypassed the Senate via a recess appointment and Scalia spent a year at Labor before returning to private practice.

In 2004, Scalia filed his first cost-benefit case, confronting the SEC on behalf of the US Chamber of Commerce over a rule that required mutual funds to find new board members outside the company. He won that case in the DC Circuit Court of Appeals and logged another big victory against the SEC in 2010, establishing himself as the go-to guy for litigating financial regulations into oblivion.

Scalia came after Dodd-Frank just two months after its passage, targeting a rule that would give shareholders more opportunities to replace corporate board members. He laid out what would become his standard argument: Yes, the new law empowered the SEC to implement the rule, but the agency had been shoddy in calculating the impact on companies’ balance sheets. A panel of three judges on the DC Circuit Court, all Republican appointees, sided with him and rebuked the agency for being “arbitrary and capricious.” Two more wins against other Dodd-Frank rules followed. In September 2012, the court struck down a new rule on commodities futures—even though the Commodity Futures Trading Commission had devoted nearly a quarter of the 81-page rule to cost-benefit analysis in anticipation of just such a showdown.

Part of the secret to Scalia’s success, his critics say, is the makeup of the DC District Court and DC Circuit Court, which have been controlled by conservative judges. “This right-wing group in the DC Circuit is one of the worst cases of judicial activism,” Frank says. “They pretend judges should be restrained, but you have several cases of them substituting their economic judgment and making decisions that affect public policy rules.” After Senate Democrats changed the filibuster rules last December, Obama’s long-blocked nominees to the DC Circuit Court of Appeals were finally approved, tilting it to a 7-to-4 liberal-conservative split. But consumer advocates shouldn’t pop the champagne too soon: It was an earlier Obama appointee who wrote the decision overturning the commodities rule.

That could be a sign of what’s to come, particularly as Scalia sets his sights on the Volcker rule, a cornerstone of Dodd-Frank that is designed to keep banks from becoming “too big to fail” by limiting their investments in hedge funds and other risky activities. When the final rule was announced in January without a financial-impact statement, Scalia was quick to pounce. “This is a disturbing reflection of how some financial-regulatory agencies are treating the economic analysis required by Congress,” he told Reuters. You could almost hear the legal pads being laid out.