You’ve heard this story before, the one that played out again the week of Thanksgiving—this time in Lakeland, Florida—where 2-year-old Taj Ayesh got his little hands on his father’s loaded pistol, pulled the trigger, and crumpled to the ground. You may have heard about 9-year-old Daniel Wiley, who was playing outside his house in Harrisburg, Texas, when a 13-year-old mishandled an unsecured shotgun, blasting Wiley in the face. You may also have heard about 2-year-old Camryn Shultz of Forty Fort, Pennsylvania, whose embittered father put a bullet in her head before turning the gun on himself. Maybe you didn’t hear about the case in which a child shot others and then committed suicide, but that also happened this year. Twice.

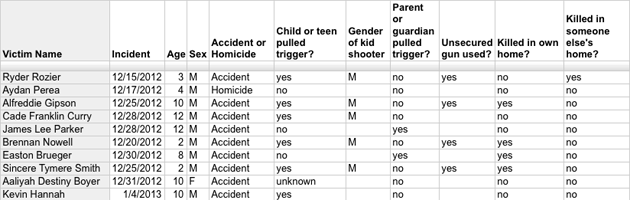

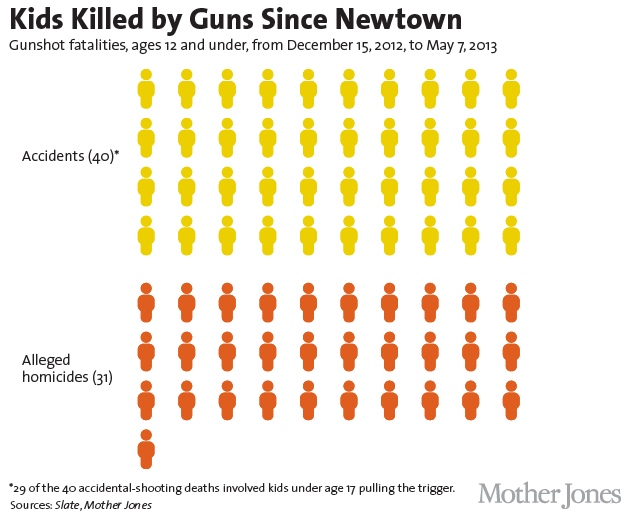

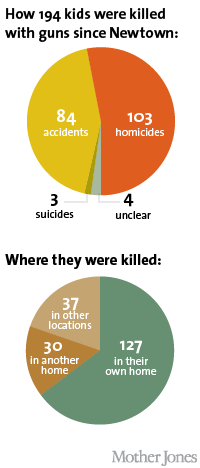

A year after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, Mother Jones has analyzed the subsequent deaths of 194 children ages 12 and under who were reported in news accounts to have died in gun accidents, homicides, and suicides. They are spread across 43 states, from inner cities to tiny rural towns.

Following Sandy Hook, the National Rifle Association and its allies argued that arming more adults is the solution to protecting children, be it from deranged mass shooters or from home invaders. But the data we collected stands as a stark rejoinder to that view:

- 127 of the children died from gunshots in their own homes, while dozens more died in the homes of friends, neighbors, and relatives.

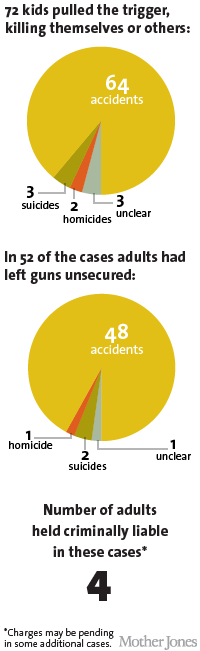

- 72 of the young victims either pulled the trigger themselves or were shot dead by another kid.

- In those 72 cases, only 4 adults have been held criminally liable.

- At least 52 deaths involved a child handling a gun left unsecured.

Additional findings include:

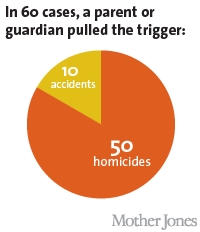

- 60 children died at the hands of their own parents, 50 of them in homicides.

- The average age of the victims was 6 years old.

- More than two-thirds of the victims were boys, as were more than three-quarters of the kids who pulled the trigger.

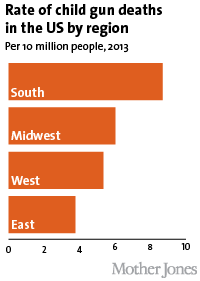

- The problem was worst over the past year in the South, which saw at least 92 child gun deaths, followed by the Midwest (44), the West (38), and the East (20).

Our investigation drew on hundreds of local and national news reports. In some cases specific details remain unclear—often these tragedies are just a blip on the media’s radar. As with previous reports in our ongoing investigation of gun violence, Mother Jones has published all the data we collected in downloadable spreadsheet form. (For an ongoing tally of reported gun deaths, see this Slate project.)

As I reported in May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that over the last decade an average of about 200 children ages 12 and under died from guns every year. But those numbers don’t capture the full scope of the problem, due to inconsistencies in how states report shootings, and because the gun lobby long ago helped kill off federal funding for gun violence research. Our media-based analysis of child gun deaths also understates the problem, as numerous such killings likely never appear in the news. New research by two Boston surgeons drawing on pediatric records suggests that the real toll is higher: They’ve found about 500 deaths of children and teens per year, and an additional 7,500 hospitalizations from gunshot wounds.

“It’s almost a routine problem in pediatric practice,” says Dr. Judith Palfrey, a former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics who holds positions at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital. Palfrey herself (who is not involved with the above study) lost a 12-year-old patient she was close with to gun violence, she told me.

No other affluent society has this problem to such an extreme. According to a recent study by the Children’s Defense Fund, the gun death rate for children and teens in the US is four times greater than in Canada, the country with the next highest rate, and 65 times greater than in Germany and Britain.

The pediatric community has been focused on elevating the issue. Public health researchers have found that 43 percent of homes with guns and kids contain at least one unlocked firearm. One study found that a third of 8- to 12-year-old boys who came across an unlocked handgun picked it up and pulled the trigger. On Tuesday, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a video emphasizing physicians’ role in keeping children safe from gun violence. The academy also issued specific recommendations this fall, including making sure firearms have trigger locks and storing them unloaded and under lock and key.

State legislators around the country have sought to require such precautions for gun owners, but the gun lobby has fought them vigorously. The NRA and other groups downplay the dangers firearms pose to children—in part by citing deficient federal data.

According to the New England Journal of Medicine, research has shown that when doctors consult with their patients about the risk of keeping firearms in a home, it leads to “significantly higher rates” of handgun removal or safe storage practices. Here, too, the NRA has done battle: It backed the so-called “Docs vs. Glocks” law passed in Florida in 2011, which forbid doctors from asking patients about firearms.

That law may have come with a price: Among the 194 child gun deaths we analyzed, 17 took place in Florida. Seven were accidents, including three involving unsecured weapons in homes. “The children were covered in blood,” a shaken witness told a reporter after toddlers in a Lake City home played with a gun and fatally shot an 11-year-old boy in the neck.

Florida’s tally was second only to that of Texas, which saw 19 children killed over the last year. By comparison, the other two of the four most populous states, California and New York, saw 11 and 3 deaths, respectively. Already known for strict gun regulations, California and New York both passed additional restrictions after Sandy Hook. Texas, meanwhile, enacted 10 new laws deregulating guns, including weakening safety training requirements for concealed-carry permit holders and blocking universities and local governments from restricting firearms. Florida tightened mental health controls this year—one of 15 states to do so—but has otherwise operated as a de facto laboratory for permissive gun laws, including its Stand Your Ground statute made famous by the Trayvon Martin case.

In scores of the cases we studied, the type of weapon involved was either unknown to law enforcement authorities or not specified in news reports. But at least 76 involved a handgun, while another 34 involved long guns. (Semi-automatic handguns are also the most common weapon used in mass shootings.)

Often when kids are killed in gun accidents, public outrage focuses on the parents. But legal repercussions are another matter: While charges may be pending in some of the 84 accidental cases, we found only 9 in which a parent or adult guardian has been held criminally liable. And in 72 cases in which a child or teen pulled the trigger, only four adults have been convicted. According to the nonpartisan Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which tracks state regulations closely, only 14 states and the District of Columbia have strong laws imposing criminal liability for negligent storage of guns with respect to children. (Florida, Texas, and California are among the 14.)

What happened a year ago in Newtown is still in some ways hard to fathom. The nation mourns again for the victims and families. But as Palfrey also puts it, “Newtown concentrated the horror in one place.” Whether by malice or tragic mistake, the day-to-day toll of children dying from guns goes on.

The data from our investigation can be viewed in two ways. See an interactive photo gallery of the 194 victims:

See the full data set behind the investigation in spreadsheet form:

For more on this story, listen to NPR’s “All Things Considered.” Also see our full special report, Newtown: One Year After, and our award-winning investigation, America Under the Gun: A Special Report on the Rise of Mass Shootings.

Research contributed by Maggie Caldwell, Nina Liss-Schultz, and AJ Vicens. Charts produced by Jaeah Lee. Video produced by Brett Brownell.