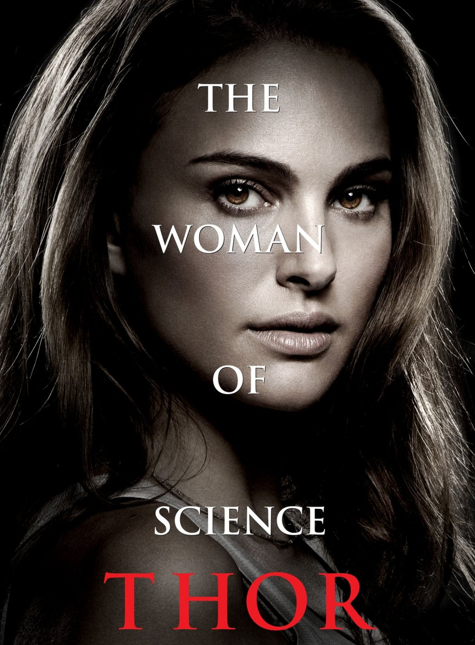

Courtesy of Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures

Yes, Thor: The Dark World—a new film about a Norse-myth-inspired superhero traveling through space and fighting elves with a hammer—had scientific consultants working on it. One of them was Sean Carroll, a theoretical physicist at the California Institute of Technology.

“Marvel is very, very interested, with every movie they make, in trying to meet with scientists,” Carroll says. “With real-world sciences and the comic-book universe, they just try to make it all hang together.”

Carroll is a 47-year-old cosmologist who researches in the fields of particle physics and general relativity, and wrote a book on cosmology and time called From Eternity to Here. He was an informal consultant on both Thor: The Dark World and Thor, its 2011 predecessor. He met with the writers, directors, and production staff to help massage the scientific details.

For the first Thor, Carroll and two other physicists (Prof. James Hartle and Kevin Hand, who was also a consultant on both Thor pictures) were introduced to director Kenneth Branagh through the Science & Entertainment Exchange, a National Academy of Sciences program that connects the entertainment industry with engineers and scientists. Carroll is married to Jennifer Ouellette, founding director of the Exchange, and has also consulted on the Fox series Bones and the Ron Howard thriller Angels & Demons.

“As a consultant, my goal isn’t to make the film consistent with the laws of physics,” Carroll says. “It’s about using details of the science to make the story more interesting…Telling a good story comes first.”

When Carroll finally saw the 2011 film, he witnessed exactly how his advice translated onto the big screen. For instance, a conversation he had with Marvel Studios chief Kevin Feige was turned into a bit of dialogue. Carroll recalls that the conversation went something like this:

KF: We need the [fictional] Bifrost Bridge to provide a way for the characters to travel great distances in space in a very short period of time.

SC: Sure, you probably want to say that it makes use of wormholes.

KF: Well, we can’t call it a “wormhole.”

SC: Why not?

KF: Sounds too ’90s.

SC: I suppose…you could call it an “Einstein-Rosen bridge.” Means the same thing.

“And what you get in actual movie is Jane Foster saying they must have used an Einstein-Rosen bridge,” Carroll says. “Kat Dennings‘ character asks, ‘what’s that?’ and Stellen says, ‘it’s a wormhole!'”

For Thor: The Dark World, Carroll lent director Alan Taylor and company a hand by giving them some pointers on a subject he knows much about: Dark matter. “They told me they needed to have darkness in the theme and wanted to know how to connect dark matter to the story.” In the film, the supervillian Dark Elf hunts for the Aether, a scary and extremely powerful source of dark matter. “This adapted physics to the screenplay,” Carroll says.

Carroll hasn’t seen the latest Thor installment, but hopes to this weekend. When asked for his assessment of the scientific accuracy of the first one, he responded as any Caltech physicist would when discussing a film about a blond alien prince flying around the universe saving Natalie Portman.

“I don’t think it is scientifically accurate, but that’s not the point,” he says. “Scientists often given Hollywood people a bad rap…But the thing to make the world a better place isn’t to complain about scientific inaccuracies in movies; it’s to constructively engage with storytellers so that they can take advantage of the science. For example, in Iron Man, realistically, Robert Downey, Jr. is not going to be able to build that suit in a cave and then fly away. But the process he goes through—designing his new suit, modeling, experimenting—this is all quite a realistic portrayal of the attitude that a scientist brings to what he or she does.”

Marvel is indeed playing up this sort of outreach to the broader scientific community. Marvel and Disney recently held their Ultimate Mentor Adventure competition for American girls (14 years or older and enrolled in grades 9-12) interested in science, tech, engineering, and mathematics. “Do you have what it takes to be the next Jane Foster?” the contest page read. The Oscar-winning Portman—who has some legit science cred to her name, including making it to the semifinals in America’s most elite high school research contest—starred in an introductory video for the contest. “Could Portman become the new role model for female scientists…?” CNN asked last week.

Carroll agrees that Portman’s Foster serves as a great role model for young women aspiring to study and work in the fields of science. But he does harbor one regret about how the character was presented, at least in the previous film. “So much of the consulting is saying, ‘What is this person going to be like?'” Carroll says. “I think they could’ve done a better job at, for instance, having her react to Thor like a physicist would react. She could have done a lot more active questioning, like, ‘What is the world of physics as you understand it?’ or ‘How exactly did you get here?'”

In the grand scheme, it’s a small objection. But it’s stuff like this that Carroll keeps in mind when he’s trying to bring some of his world to Hollywood. “It’s about getting the attitudes of scientists right!” he emphasizes. “Scientists have their own flaws, their own jealousies, they react in certain ways—and that’s humanizing. It’s a big part of how we can help them produce a more accurate portrayal of the profession in film and television.”

Here’s a trailer for Thor: The Dark World: