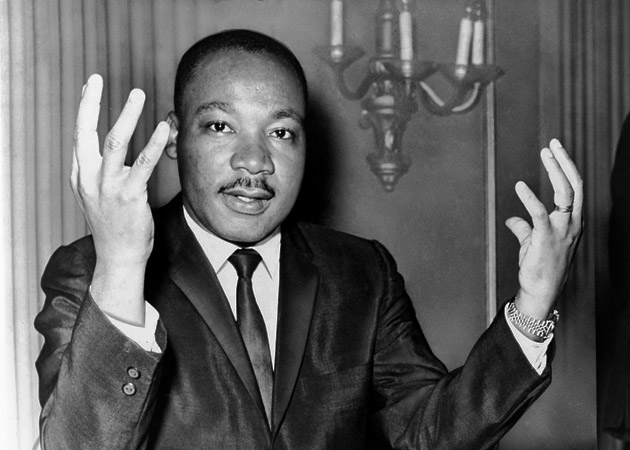

Ryan ShapiroStephanie Crumley

Ryan Shapiro has just wrapped up a talk at Boston’s Suffolk University Law School, and as usual he’s surrounded by a gaggle of admirers. The crowd, consisting of law students, academics, and activist types, is here for a panel discussion on the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, a 2006 law targeting activists whose protest actions lead to a “loss of profits” for industry. Shapiro, a 37-year-old Ph.D. student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, contributed a slideshow of newspaper headlines, posters, and government documents from as far back as the 1800s depicting animal advocates as a threat to national security. Now audience members want to know more about his dissertation and the archives he’s using. But many have a personal request: Would Shapiro help them discover what’s in their FBI files?

He is happy to oblige. According to the Justice Department, this tattooed activist-turned-academic is the FBI’s “most prolific” Freedom of Information Act requester—filing, during one period in 2011, upward of two documents requests a day. In the course of his doctoral work, which examines how the FBI monitors and investigates protesters, Shapiro has developed a novel, legal, and highly effective approach to mining the agency’s records. Which is why the government is petitioning the United States District Court in Washington, DC, to prevent the release of 350,000 pages of documents he’s after.

Invoking a legal strategy that had its heyday during the Bush administration, the FBI claims that Shapiro’s multitudinous requests, taken together, constitute a “mosaic” of information whose release could “significantly and irreparably damage national security” and would have “significant deleterious effects” on the bureau’s “ongoing efforts to investigate and combat domestic terrorism.”

So-called mosaic theory has been used in the past to stop the release of specific documents, but it has never been applied so broadly. “It’s designed to be retrospective,” explains Kel McClanahan, a DC-based lawyer who specializes in national security and FOIA law. “You can’t say, ‘What information, if combined with future information, could paint a mosaic?’ because that would include all information!”

Fearing that a ruling in the FBI’s favor could make it harder for journalists and academics to keep tabs on government agencies, open-government groups including the Center for Constitutional Rights, the National Security Archive, and the National Lawyers Guild (as well as the nonprofit news outlet Truthout and the crusading DC attorney Mark Zaid) have filed friend-of-the-court briefs on Shapiro’s behalf. “Under the FBI’s theory, the greater the public demand for documents, the greater need for secrecy and delay,” says Baher Azmy, CCR’s legal director.

Shapiro takes pride in his “most prolific” status, but it’s not an honorific he had in mind when he set out to learn how the FBI came to view animal rights activists as the nation’s “number one domestic terrorism threat.” He ran into a wall when he first began requesting significant numbers of documents from the bureau in 2010. He needed case numbers, file names, and names of field offices where investigations originated, and even when he had them, the FBI often claimed it didn’t have any relevant documents. So he began reading everything he could find on FOIA law, including the FBI’s internal regulations and court filings describing how it conducts its searches.

When he started using privacy waivers, Shapiro realized he was on to something. Suppose you and I volunteered for the animal rights group PETA. If Shapiro requested all PETA-related FBI documents, he might get something back, but any references to us would be blacked out. If he requested documents related to us, he’d probably get nothing at all. But if he filed his PETA request along with privacy waivers signed by us, the FBI would be compelled to return all PETA documents that mention us—with the relevant details uncensored.

Shapiro began calling up old friends and asking for waivers. Coming of age amid the 1990s punk scene, he’d been drawn to animal rights causes and took part in their actions. He walked into foie gras facilities to film sick and injured ducks, several of which he rescued, and locked himself to the doors of fur salons. And while he no longer does such things, he has kept in touch with people who do.

Armed with signed privacy waivers, he sent out a few experimental requests—he calls them “submarine pings”—and when the FBI returned more than 100 pages on a close friend, he knew he’d struck gold. The response included pages of information that Shapiro had requested previously, but that the FBI had claimed didn’t exist. Using case details from those documents and a handful of additional waivers, he filed a new set of requests.

Bit by bit, the black boxes began to go away. “Each response is a teeny little window opened into the backrooms of these deliberately byzantine FBI filing systems,” Shapiro told me. “You get enough windows, and then you have the light you need to see what’s back there.” Soon Shapiro was submitting hundreds of requests, yielding tens of thousands of pages.

One of his privacy waivers had my name on it. As an independent journalist whose website and recent book focus on agribusiness, animal rights, and ecoterrorism, I’ve known Shapiro for years. I’ve quoted him in stories and written about documents he’s procured showing that the FBI considered terrorism charges against activists who engaged in undercover investigations of factory farm conditions. I knew from filing my own FOIA requests that the FBI’s Counter Terrorism Unit has monitored my website and speaking events, and so I agreed to sign a waiver. I wanted to see whether Shapiro’s technique would reveal anything new. I never found out, though, since the FBI has stopped complying with his requests.

In 2012, after Shapiro sued the FBI to release the blocked documents, the Justice Department responded by asking the court for what’s known as an Open America stay—a delay tactic dating back to a Watergate-era court decision. FOIA experts consider it a nuclear option, and the courts say it is meant for “exceptional circumstances,” when an agency is deluged with requests. Under normal circumstances, government agencies are allowed 20 days to say whether (if not when) they will comply with a given query. For example, in a recent case in which the Electronic Privacy Information Center sued the FBI for documents about cellphone tracking, the bureau asked for 14 extra months, claiming—as it has in Shapiro’s case—an unexpectedly high FOIA workload. A federal judge denied the stay, pointing out that the annual volume of documents requests received by the FBI has decreased “significantly” since 2008.

In Shapiro’s case, the feds want seven years to determine whether the docs can be released. “That would be a world-record setter,” says Dan Metcalfe, who, after more than a quarter century running the Justice Department’s Office of Information and Privacy, now heads the Collaboration on Government Secrecy at American University Law School. “The FBI never did anything like this even back in the darkest days of George W. Bush or Ronald Reagan.”

The FBI claims that it cannot discuss the case in open court “without damaging the very national security law enforcement interests it is seeking to protect.” Instead, it has filed a secret declaration outlining its case. “This is an especially circular and Kafkaesque line of argument,” Shapiro counters. “The FBI considers it a national security threat to make public its reasoning for considering it a national security threat to use federal law to request information about the FBI’s deeply problematic understanding of national security threats.”

Shapiro’s attorney, Jeffrey Light, was able to obtain a heavily redacted version of the FBI’s declaration. Among other things, it cites the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act and says that 81 of Shapiro’s FOIA requests covering 64 individuals, groups, and publications, relate to “animal rights extremism.”

The FBI, oddly enough, is processing his requests involving arsons by the fringe Animal Liberation Front but blocking documents concerning movement mainstays like Mercy for Animals. Some of the disputed requests pertain to anti-animal-rights groups such as the Center for Consumer Freedom. The FBI’s so-called extremists span a wide spectrum—from former ALF operative Rod Coronado to Jon Camp, who has no criminal record and whose job consists of handing out leaflets for a group called Vegan Outreach. I was surprised to learn that I, too, am among them—and that the bureau asserts that releasing information about me and my book would interfere with law enforcement proceedings.

A ruling is expected in the case within the next few months. In the meantime, Shapiro continues writing his dissertation, collecting waivers, and drafting FOIA requests late at night while watching television with his wife. Lately he’s been interested in getting the FBI files of famous punk and hip-hop artists. He acknowledges that his work has become a borderline obsession. When Daniel Ellsberg visited MIT for a lecture, Shapiro had lunch with him and some other grad students. He walked away with a privacy waiver from the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers.

****

The clip below shows Shapiro at an animal-rights conference, using some of the documents he obtained to make fun of the FBI’s investigative methods.