<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=50749924&src=id">Rene Jansa</a>/Shutterstock

This story first appeared on the ProPublica website.

The IRS division responsible for flagging Tea Party groups has long been an agency afterthought, beset by mismanagement, financial constraints and an unwillingness to spell out just what it expects from social welfare nonprofits, former officials and experts say.

The controversy that erupted in the past week, leading to the ousting of the acting Internal Revenue Service commissioner, an investigation by the FBI, and congressional hearings that kicked off Friday, comes against a backdrop of dysfunction brewing for years.

Moves launched in the 1990s were designed to streamline the tax agency and make it more efficient. But they had unintended consequences for the IRS’s Exempt Organizations division.

Checks and balances once in place were taken away. Guidance frequently published by the IRS and closely read by tax lawyers and nonprofits disappeared. Even as political activity by social welfare nonprofits exploded in recent election cycles, repeated requests for the IRS to clarify exactly what was permitted for the secretly funded groups were met, at least publicly, with silence.

All this combined to create an isolated office in Cincinnati, plagued by what an inspector general this week described as “insufficient oversight,” of fewer than 200 low-level employees responsible for reviewing more than 60,000 nonprofit applications a year.

In the end, this contributed to what everyone from Republican lawmakers to the president says was a major mistake: The decision by the Ohio unit to flag for further review applications from groups with “Tea Party” and similar labels. This started around March 2010, with little pushback from Washington until the end of June 2011.

“It’s really no surprise that a number of these cases blew up on the IRS,” said Marcus Owens, who ran the Exempt Organizations division from 1990 to 2000. “They had eliminated the trip wires of 25 years.”

Of course, any number of structural fixes wouldn’t stop rogue employees with a partisan ax to grind. No one, including the IRS and the inspector general, has presented evidence that political bias was a factor, although congressional and FBI investigators are taking another look.

But what is already clear is that the IRS once had a system in place to review how applications were being handled and to flag potentially problematic ones. The IRS also used to show its hand publicly, by publishing educational articles for agents, issuing many more rulings, and openly flagging which kind of nonprofit applications would get a more thorough review.

All of those checks and balances disappeared in recent years, largely the unforeseen result of an IRS restructuring in 1998, former officials and tax lawyers say.

“Until 2008, we had a dialogue, through various rulings and cases and the participation of various IRS officials at various ABA meetings, as to what is and what is not permissible campaign intervention,” said Gregory Colvin, the co-chair of the American Bar Association subcommittee that dealt with nonprofits, lobbying, and political intervention from 1991 to 2009.

“And there has been absolutely no willingness in the last five years by the IRS to engage in that discussion, at the same time the caseload has exploded at the IRS.”

The IRS did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Social welfare nonprofits, which operate under the 501(c)(4) section of the tax code, have always been a strange hybrid, a catchall category for nonprofits that don’t fall anywhere else. They can lobby. For decades, they have been allowed to advocate for the election or defeat of candidates, as long as that is not their primary purpose. They also do not have to disclose their donors.

Social welfare nonprofits were only a small part of the exempt division’s work, considered minor when compared with charities. When the groups sought IRS recognition, the agency usually rubber-stamped them. Out of 24,196 applications for social welfare status between 1998 and 2009, the exempt organizations division rejected only 77, according to numbers compiled from annual IRS data books.

Into this loophole came the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision in January 2010, which changed the campaign-finance game by allowing corporate and union spending on elections.

Sensing an opportunity, some political consultants started creating social welfare nonprofits geared to political purposes. By 2012, more than $320 million in anonymous money poured into federal elections.

A couple of years earlier, beginning in 2010, the Cincinnati workers had flagged applications of tiny Tea Party groups, according to the inspector general, though the groups spent almost no money in federal elections.

The main question raised by the audit is how the Cincinnati office and superiors in Washington could have gotten it so wrong. The audit shows no evidence that these workers even looked at records from the Federal Election Commission to vet much larger groups that spent hundreds of thousands and even millions in anonymous money to run election ads.

The IRS Exempt Organizations division, the watchdog for about 1.5 million nonprofits, has always had to deal with controversial groups. For decades, the division periodically listed red flags that would merit an application being sent to the IRS’s Washington, D.C., headquarters for review, said Owens, the former division head.

In the 1970s, that meant flagging all applications for primary and secondary schools in the south facing desegregation. In the 1980s, during the wave of consolidation in the health-care industry, all applications from health-care nonprofits needed to be sent to headquarters. The division’s different field offices had to send these applications up the chain.

“Back then, many more applications came to Washington to be worked—the idea was to have the most sensitive ones come to Washington,” said Paul Streckfus, a former IRS lawyer who screened applications at headquarters in the 1970s and founded the industry publication EO Tax Journal in 1996.

Because this list was public, lawyers and nonprofits knew which cases would automatically be reviewed.

“We had a core of experts in tax law,” recalled Milton Cerny, who worked for the IRS, mainly in Exempt Organizations, from 1960 to 1987. “We had developed a broad group of tax experts to deal with these issues.”

In the 1980s, the division issued many more “revenue rulings” than issued in recent years, said Cerny, then head of the rulings process. These revenue rulings set precedents for the division. Revenue rulings along with regulations are basically the binding IRS rules for nonprofits.

“We would do a revenue ruling, so the public and agents would know,” Cerny said. “Over the years, it apparently was felt that a revenue ruling should only be published at an extraordinary time. So today you’re lucky if you get one a year. Sometimes it’s less than that. It’s amazing to me.”

Other checks and balances had existed too. Not only were certain kinds of applications publicly flagged, there was another mechanism called “post-review,” Owens said. Headquarters in Washington would pull a random sample every month from the different field offices, to see how applications were being reviewed. There was also a surprise “saturation review,” once a year, for each of the offices, where everything from a certain time period needed to be sent to Washington for another look.

So internally, the division had ways, if imperfect, to flag potential problems. It also had ways of letting the public know what exactly agents were looking at and how the division was approaching controversial topics.

For instance, there was the division’s “Continuing Professional Education,” or CPE, technical instruction program. These articles were supposed to be used for training of line agents, collecting and putting out the agency’s best information on a particular topic—on, say, political activity by social welfare nonprofits in 1995.

“People in a group would write up their thoughts: ‘Here’s the law,'” said Beth Kingsley, a Washington lawyer with Harmon, Curran, Spielberg & Eisenberg who’s worked with nonprofits for almost 20 years. “It wasn’t pushing the envelope. It was, ‘This is how we see this issue.’ It told us what the IRS was thinking.”

The system began to change in the mid-1990s. The IRS was having trouble hiring people for low-level positions in field offices like New York or Atlanta—the kinds of workers that typically reviewed applications by nonprofits, Owens said.

The answer to this was simple: Cincinnati.

The city had a history of being able to hire people at low federal grades, which in 1995 paid between $19,704 and $38,814 a year—almost the same as those federal grades paid in New York City or Chicago. (Adjusted for inflation, that’s between $30,064 and $59,222 now.)

“That was well below what the prevailing rate was in the New York City area for accountants with training,” Owens said. “We had one accountant who just had gotten out of jail—that’s the sort of people who would show up for jobs. That was really the low point.”

So in 1995, the Exempt Organizations division started to centralize. Instead of field offices evaluating applications for nonprofits in each region, those applications would all be sent to one mailing address, a post-office box in Covington, Ky. Then a central office in Cincinnati would review all the applications.

Almost inadvertently, because people there were willing to work for less than elsewhere, Cincinnati became ground zero for nonprofit applications.

For the time being, the checks remained in place. The criteria for flagged nonprofits were still made public. The Continuing Professional Education text was still made public. Saturation reviews and post reviews were still in place.

But by 1998, after hearings in which Republican Senator Trent Lott accused the IRS of “Gestapo-like” tactics, a new law mandated the agency’s restructuring. In the years that followed, the agency aimed to streamline. For most of the ‘90s, the IRS had more than 100,000 employees. That number would drop every year, to slightly less than 90,000 by 2012.

Change also came to the Exempt Organizations division.

The IRS tried to remove discretion from lower-level employees around the country by creating rules they had to follow. While the reorganization was designed to centralize power in the agency’s Washington headquarters, it didn’t work out that way.

“The distance between Cincinnati and Washington was such that soon Cincinnati became a power center,” said Streckfus, the former IRS lawyer.

Following reorganization, many highly trained lawyers in Washington who previously handled the most sensitive nonprofit applications were reassigned to focus on special projects, he said.

Owens, who left the IRS in 2000 but stayed in touch with his old division, said the focus on efficiency meant “eliminating those steps deemed unimportant and anachronistic.”

In 2003, the saturation reviews and post reviews ended, and the public list of criteria that would get an application referred to headquarters disappeared, Owens said. Instead, agents in Cincinnati could ask to have cases reviewed, if they wanted. But they didn’t very often.

“No one really knows what kinds of cases are being sent to Washington, if any,” Owens said. “It’s all opaque now. It’s gone dark.”

By the end of 2004, the Continuing Professional Education articles stopped.

Recommendations from an ABA task force for IRS guidelines on social welfare nonprofits and politics that same year were met with silence.

Even the IRS’s Political Activities Compliance Initiative, which investigated complaints of charities engaged in politics—primarily churches—closed up shop in early 2009 after less than five years, without any explanation.

Both before and after the changes, the Exempt Organizations division has been a small part of the IRS, which is focused on collecting money and chasing delinquent taxpayers.

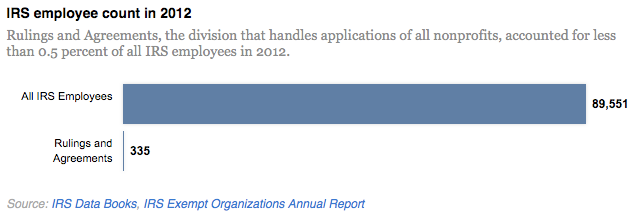

Source: IRS Data Books, IRS Exempt Organizations Annual Report

Of the 90,000 employees at the agency last year, only 876 worked in the Exempt Organizations’ division, or less than 1 in 1,000 employees.

Of those, 335 worked in the office that actually handles applications of nonprofits.

Most of those—about 300—worked in Cincinnati, Streckfus estimates. The rest were at headquarters, in Washington D.C.

In Cincinnati, the employees’ primary job was sifting through the applications of nonprofits, making determinations as to whether a nonprofit should be recognized as tax-exempt. In a press release Wednesday, the IRS said fewer than 200 employees were responsible for that work.

In 2012, these employees received 60,780 applications. The bulk of those—51,748—were from groups that wanted to be recognized as charities.

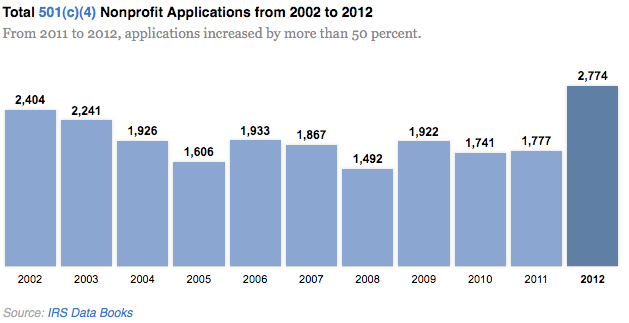

But the number of social welfare nonprofit applications spiked from 1,777 in 2011 to 2,774 in 2012. It’s impossible to say how many of those groups indicated whether they would engage in politics, or why the number of applications increased. The IRS said Wednesday that it “has seen an increase in the number of tax-exempt organization applications in which the organization is potentially engaged in political activity,” including both charities and social welfare nonprofits, but didn’t specify any numbers.

Source: IRS Data Books

On average, one employee in Cincinnati would be responsible for going through roughly one application per day.

Some would be easy—say, a local soup kitchen. But to evaluate whether a social welfare nonprofit has social welfare as its primary purpose, the agent is supposed to use a “facts and circumstances” test. There is no checklist. Reviewing just one social welfare nonprofit could take days or weeks, to look through a group’s website, track down TV ads and so forth.

“You’ve got 60,000 applications coming through, and it’s hard to do that with the number of agents looking at them,” said Philip Hackney, who was in the IRS’s chief counsel office in Washington between 2006 and 2011 but said he wasn’t involved in the Tea Party controversy. “The reality is that they cannot do that, and that’s why you’re seeing them pick stuff out for review. They tried to do that here, and it burned them.”

As we have previously reported, last year the same Cincinnati office sent ProPublica confidential applications from conservative groups. An IRS spokeswoman said the disclosures were inadvertent.

Mark Everson, IRS commissioner for four years during the George W. Bush administration, said he believed the fact that the division is understaffed is relevant, but not an excuse for what happened. “The whole service is under-funded,” he pointed out.

And Dan Backer, a lawyer in Washington who represented six of the groups held up because of the Tea Party criteria, said he doesn’t buy the notion that low-level employees in Cincinnati were alone responsible.

“It doesn’t just strain credulity,” Backer said. “It broke credulity and left it laying on the road about a mile back. Clearly these guys were all on the same marching orders.”

The inspector general’s audit was prompted last year after members of Congress, responding to complaints by Tea Party groups, asked for it.

Like former officials interviewed by ProPublica, the audit suggests that officials at IRS headquarters in Washington were unable to manage their subordinates in Cincinnati. When Lois Lerner, the Exempt Organizations division director in Washington, learned in June 2011 about the improper criteria for screening applications, she instructed that they be “immediately revised.”

But just six months later, Cincinnati employees changed the revised criteria to focus on “organizations involved in limiting/expanding government” or “educating on the Constitution.” They did so “without executive approval.”

“The story people are overlooking is: Congress is complaining about underpaid, overworked employees who are not adequately trained,” said Bryan Camp, a former attorney in the IRS chief counsel’s office.

In the end, after all the millions of anonymous money spent by some groups to elect candidates in 2012, after all the groups that said in their applications that they would not spend money to elect candidates before doing exactly that, after the Cincinnati office flagged conservative groups, the IRS approved almost all the new applications. Only eight applications were denied.