Donglai Gong with the Slocum glider on the flight deck of USCG icebreaker Healy. Donglai Gong.

Editor’s note: Julia Whitty is on a three-week-long journey aboard the the US Coast Guard icebreaker Healy, following a team of scientists who are investigating how a changing climate might be affecting the chemistry of ocean and atmosphere in the Arctic.

One of the more engaging stories on the ship has been that of Donglai Gong, an assistant professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, and his Slocum glider, named after the legendary 19th-century sailor Joshua Slocum, the first man to sail single-handedly around the world.

This Slocum is an unmanned robot that can fly underwater for 20 to 30 kilometers a day for weeks to months collecting high-resolution data on temperature, salinity, pressure, and other water qualities.

Plan A was to deploy the glider in the region of Barrow Canyon, a dynamic pathway of Pacific Ocean water into the Arctic Ocean. But due to the bowhead whaling season underway, Plan B in the Chukchi Sea was launched.

![Donglai Gong watches the glider launch from the Healy Bridge. Julia Whitty.] Donglai Gong watches the glider launch from the Healy Bridge. Julia Whitty.]](https://fullsite.motherjones.com/wp-content/uploads/images/donglai-gong-watching-glider-launch-630.jpg) Donglai Gong watches the glider launch from the Healy Bridge. Julia Whitty.

Donglai Gong watches the glider launch from the Healy Bridge. Julia Whitty.

But before Plan B could get started, Donglai needed to perform a buoyancy test on the glider. That was conducted 70 kilometers away from the Plan B launch site. Unfortunately, the glider never surfaced from this test and when the crew on the small boat pulled in the buoy attached to the glider to see what was up, the glider was gone.

Donglai was watching from the Healy Bridge. His excitement—I thought he looked like an expectant father—gave way to shock at the realization that the glider might be lost and his experiment abruptly ended. Worse, the glider wasn’t even his own, but on loan to him from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI). Ooops.

Donglai with email from the glider. Julia Whitty

Donglai with email from the glider. Julia Whitty

But the story wasn’t over. An hour and half later Donglai got an email on his iPhone. It was a message from the glider, which had kicked into emergency mode and surfaced to uplink its location to a satellite.

By then night had fallen and recovery wouldn’t be possible until the following morning. Donglai made the risky but scientifically rewarding decision to leave the glider where it was and to ask it to its start its mission right there, 70 km away from the Plan B starting point.

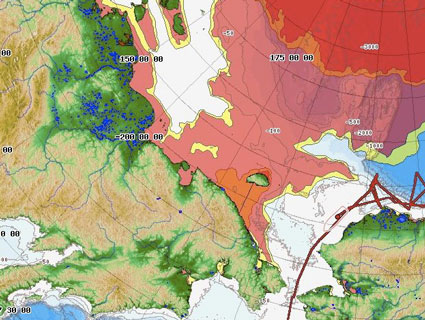

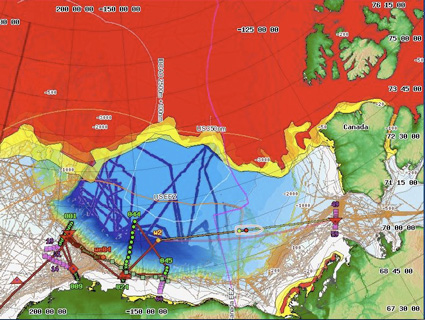

![Map of the glider's flight from 12 to 20 October 2012 in the Arctic Ocean. Steve Roberts / National Center for Atmospheric Research.] Map of the glider's flight from 12 to 20 October 2012 in the Arctic Ocean. Steve Roberts / National Center for Atmospheric Research.]](https://fullsite.motherjones.com/wp-content/uploads/images/flight-of-the-slocum-glider-10-2102-630.jpg) Map of the glider’s flight from 12 to 20 October 2012 in the Arctic Ocean. Steve Roberts / National Center for Atmospheric Research.]

Map of the glider’s flight from 12 to 20 October 2012 in the Arctic Ocean. Steve Roberts / National Center for Atmospheric Research.]

So the little glider that could jumped the starting pistol and took off towards the Beaufort Sea on Amended Plan B.

In the map above you can see the eventual flight path of the glider, here named we04. For eight days it flew roughly 200 nautical miles along the outer edge of the Beaufort shelf where shallower water drops off to deeper water. A current flowing in the same direction helped the glider on its way. Each green point on the map marks where the glider surfaced every ~2.5 hours to upload its data collected roughly every 1 kilometer of distance travelled.

From unintended launch to successful retrieval, Donglai, with assistance from colleagues at WHOI and Rutgers University, kept the glider on its track, flying towards its eventual rendezvous location with Healy last Saturday.

Last night Donglai let me listen in on some of the recordings the glider had captured from its travels across the Beaufort Sea, including calls that sounded to me like bearded seals. Part 2 of his project will be to test using acoustics as a way to communicate with a glider or gliders deployed under the Arctic ice pack. Maybe next year.

Donglai’s glider research was conceived on last year’s Healy cruise with his (then) postdoc mentor Bob Pickart at WHOI, Principle Investigator on that cruise and on this one too.