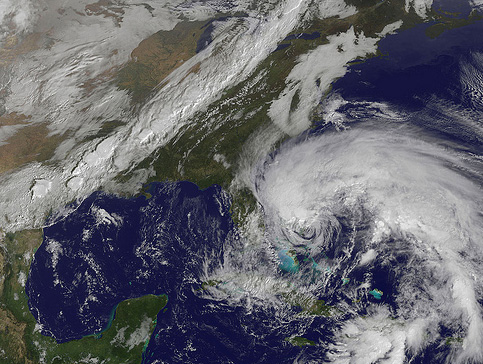

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/8125127055/sizes/m/in/photostream/">NASA Goddard Photo and Video</a>/Flickr

By now you’ve already heard about Hurricane Sandy. Or Frankenstorm. Or the Snowincane, if you prefer. As I write this, the storm is barreling toward the continental United States, promising to wreck havoc on the coastal Mid-Atlantic and New England.

It’s supposed to hit coastal Virginia, where I’ve spent quite a bit of time in the past few months reporting about sea level rise, storm surges, and efforts to make communities safer. You’ll have to wait a bit longer for that piece, but in the mean time, Sandy is a good reminder of what some regions of the country are up against.

Sure, this region does get big storms. There was Hurricane Isabel in 2003, a Nor’easter named Ernesto in 2006, Nor’Ida in 2009. In August 2011 they got Hurricane Irene. But sea level rise makes everything worse. Higher sea levels mean bigger storm surges and more damage to coastal regions.

Tide measurements have found that the sea level on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula has risen 14.5 inches in the past 100 years, and scientists expect the seas here to rise another 27.2 inches by the end of the century. Overall, sea level is rising four times faster along the east coast of the US than the global average. The area along the Chesapeake Bay is particularly at risk, because the ground is sinking as the seas are rising.

In the US, we have 4,514 miles of shoreline—20 percent our total miles of coastline—that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says is highly vulnerable to sea level rise. That includes 82 percent of Virginia’s coast. You can see what that means for storm surges with this great map that Climate Central created. Jeff Masters, the director of meteorology at Weather Underground, says we can expect 3 to 6 foot storm surges where Sandy makes landfall.

Climate change is already speeding up sea-level rise. But it’s also making mega storms more likely. A warmer climate and more moisture in the atmosphere makes for more extreme storms, as Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research explains. As Masters put it, “I call it being on steroids kind of for the atmosphere.”

Experts are already projecting that Sandy will be a billion-dollar disaster for the US. Last year, Irene alone causing $4.3 billion in losses—and that was just one of 14 storms that cost at least a billion dollars. And while damage caused by a storm like Sandy can be expensive for people who live in its path, it’s also costly for everyone else: After Social Security, the National Flood Insurance Program is the second largest fiscal liability for the US government, insuring $527 billion of assets in the coastal flood plain. Private flood insurance is difficult, if not impossible, to come by.

“This is going to be bad, but if we continue along this path of carbon pollution, it’s just going to be a lot worse,” says Amanda Staudt, a senior scientist with the National Wildlife Federation based in Reston, Va.—which is also expected to be hit by the storm. “Every time one of these disasters starts unfolding that clearly has a signature of a climate change impact, I begin to think that maybe this will be the time people will get it, that is what climate change means for us.”