<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mitt_Romney_Steve_Pearce_event_056.jpg">Wikimedia/Matthew Reichbach</a>

Mitt Romney recently released the names of more than 300 retired senior military officers who have endorsed his candidacy for president. The list includes prominent fans of the Iraq War and Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. But what can we glean from the names more generally? A whole lot—and I’ve enlisted Mother Jones‘ crack data visualization team to help.

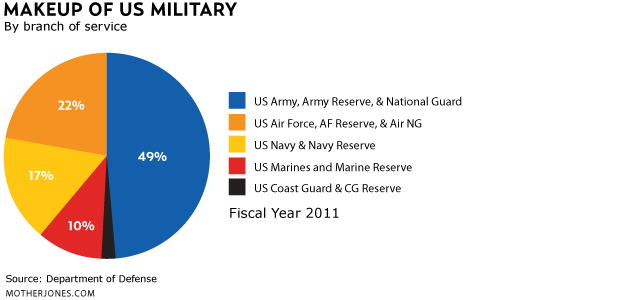

If you were to look at the composition of today’s American military by branch, it would look like this:

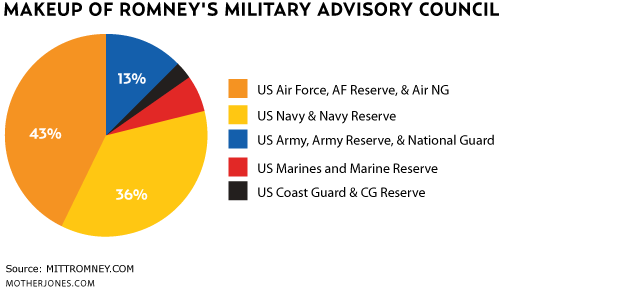

This makes sense: The Army’s got the most personnel—more than a million soldiers—and bears the heaviest burden in our overseas wars. But Romney’s generals and admirals don’t break down like this at all:

They include far fewer ground-war veterans—soldiers and Marines—and come predominantly from the Air Force and Navy. What could explain the disparity? Well, a lot of things. For one, the Navy has a lot of hidebound conservative-friendly hierarchical traditions. For another, the Air Force has long enjoyed a reputation as the most socially conservative of the services.

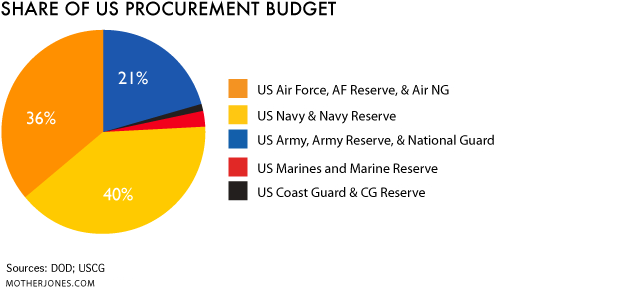

But beyond that, there could be another factor at play in the composition of Romney’s military support: money. Here’s another chart, showing the relative sizes of the budget each service got in fiscal 2012 for “procurement,” i.e., how much they could spend on contractor-built toys like planes, ships, and weapons:

Check out the resemblance between the second and third pie charts: While Romney’s military advisory council may not resemble the armed forces’ overall composition, it closely mirrors how much each respective service spends to buy stuff.

Despite the fact that it’s the largest branch of service by body count, the Army can’t come close to the Navy and Air Force when it comes to big-ticket tech and coveted pork projects. After all, ships don’t sail in deserts and soldiers don’t fly jets. Retired flag officers are likelier than civilians to work as “Beltway bandits”—lobbyists and contractors trying to grab military cash for often-bloated and wasteful priorities—and ex-Air Force generals and ex-Navy admirals are the best folks to cajole Congress into buying a new behind-schedule fighter jet or bankrolling an extra Virginia-class submarine.

These monied veterans no doubt hear a nightingale’s song when Romney complains about the size of the Navy, rails against the age of US military tanker aircraft, and pledges to spend 4 percent of GDP on defense (a move that could cost Americans another $2.1 trillion dollars). Just last week in a foreign policy speech carefully designed to boost his credibility as a possible commander in chief, Romney vowed that he would “restore our Navy to the size needed to fulfill our missions by building 15 ships per year.” That’s a nearly 70 percent boost over current shipbuilding levels—hardly the hallmark of a fiscal conservative.

It’s unclear exactly what effect all these promises will have on national security, but one thing seems clear: They should keep defense contractors safe from attacks for the next four years.