Photoillustration by Nick Baumann ; original photo by <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=steam+roller&search_group=#id=61267165&src=cca07f35536f02442df18c35a2de120e-1-6">Krivosheev Vitaly</a>/Shutterstock

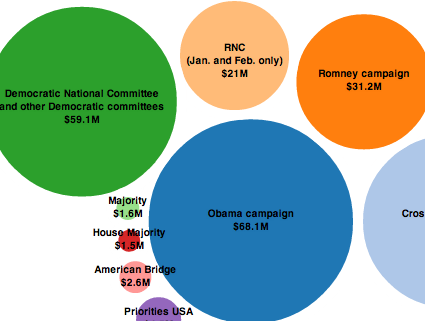

Super-PACs are a staple of the 2012 presidential race. Barack Obama, Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, and Ron Paul all have at least one. The Karl Rove-inspired American Crossroads super-PAC is so powerful that it has begun elbowing aside the Republican National Committee as the key force in national GOP politics.

Now a new breed of super-PACs is taking aim at state and local campaigns—elections where they may get even more bang for their buck.

Some of the new super-PACs are state-level groups that are also active in national politics. Others—including USA Super-PAC, created earlier this month by conservative attorney James Bopp Jr.—are organized at the federal level but will focus on specific primaries and state races.

Bopp, the Republican attorney who argued Citizens United all the way to the Supreme Court, says his group will back true conservative candidates in Republican primary contests around the country. He won’t say which ones, or how much money the group will spend.

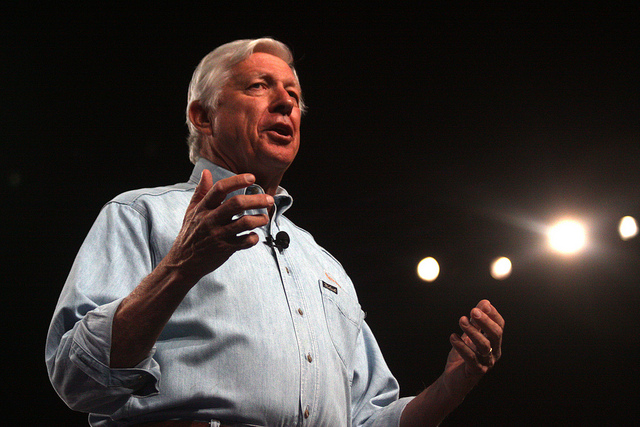

Another major player is the Campaign for Primary Accountability, which aims to boot longtime incumbents out of Congress. Bankrolled mostly by Houston construction giant Leo Linbeck III, CFPA tries to make congressional races more competitive by bashing veteran pols who are facing reelection; the super-PAC has already helped oust four-term House Rep. Jean Schmidt (R-Ohio) and nudge 15-term Rep. Dan Burton (R-Ind.) into retirement.

Last month Linbeck—whom Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D-Ohio), another politician facing CFPA attacks, called an “anarchist”—explained the logic behind his super-PAC to Mother Jones. “It’s not just a matter of ‘Hey, they’ve been there a long time, let’s get rid of them,'” he said. “It’s more like they’ve been there a long time and they’re disconnected from the voters in their district, and they would win without some other force coming in. We’re that other force.”

Federal super-PACs aren’t the only ones going local: State-registered super-PACs are getting into the game too. Some focus on just one or two races, others on numerous statewide races where a little money goes a long way. North Carolina’s first super-PAC, the Raleigh-based American Foundation Committee, has spent $366,000 to help federal prosecutor George Holding win North Carolina’s 13th congressional district. The biggest donors to the group: Holding’s own kin. Frank and Ella Holding, the candidate’s aunt and uncle, and two of Holding’s cousins gave $100,000 each, the Raleigh News and Observer reports, as did two of Holding’s cousins. Three more cousins each chipped in $17,000.

In Illinois, Personal PAC, a 34-year-old group that supports abortion rights, created the state’s first super-PAC in March. Terry Cosgrove, Personal PAC’s president and CEO, says his organization will be active in two-to-three-dozen state legislative races. He declined to say what Personal PAC’s super-PAC 2012 spending will be but said spending in past elections reached as high as $1.2 million.

Cosgrove says Personal PAC sued to force Illinois to allow state-level super-PACs—if only to fight right-to-life groups that, with Bopp’s help, have toppled numerous campaign spending limits. “Our whole argument was we just want to play on an even playing field,” Cosgrove says. “If everyone else can spend unlimitedly, then we need to as well.”

The number of state-level super-PACs is likely to grow, and don’t be surprised to see wealthy donors deploy their money in both federal and local politics—they always have. Bob Perry, the homebuilding magnate who is among the top donors to national Republican super-PACs, dished out $9.8 million at the state level between 2008 and 2010, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics. Fred Eychaner, an Obama campaign bundler who gave $500,000 to a pro-Obama super-PAC, also gave $3.8 million for state races. And Foster Friess, the Wyoming-based financier who bankrolled a super-PAC that backed Rick Santorum’s presidential campaign, doled out $856,170 for state-level campaigns.

How much further does $10,000 or $100,000 go at the state level? According to a Pew Center on the States analysis, in the mid-2000s the average cost of a winning state Senate campaign was anywhere from $5,713 (North Dakota) to $938,522 (California). In Arizona it was $36,696; in Wisconsin, $140,287; in North Carolina, $234,031. By contrast, the average cost of a US Senate seat in 2010 was $9.2 million.

Super-PACs playing at the state level don’t need to drop millions to make a big impact, says Neil Reiff, a veteran Democratic election attorney. In a crowded state-level or congressional primary with three or four candidates, a little money goes a long way. “If you’ve got a field with little or no name recognition,” Reiff says, “you can drown out everyone else.”

And although the Federal Election Commission, the nation’s political money watchdog, requires federal super-PACs reveal their donors on a periodic basis, disclosure at the state level is scattershot, says Edwin Bender, executive director of the National Institute on Money in State Politics. “Late, fragmented, and non-existent reporting are all problems at the state level,” Bender recently told the Columbia Journalism Review. “If super-PACs are going to play at the state level, we’re not going to find out until later, and it will probably happen in a very different way than in congressional or presidential races.”