[Editor’s note: This article is adapted from David Corn’s new book, Showdown: The Inside Story of Obama’s Fight to Save His Presidency. Also read the inside story of the tense White House night during the bin Laden raid.

Illustration: Eddie Guy

Illustration: Eddie Guy

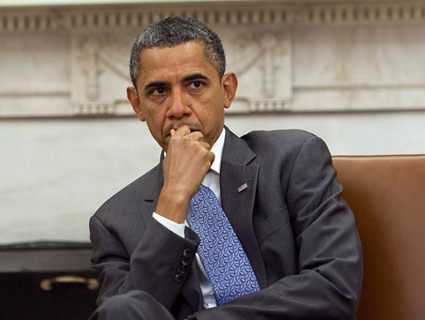

It was the spring of 2011, and Barack Obama was preparing for a Big Speech about the deficit. He wanted to counter the draconian budget plan released by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) that slashed government programs and ended the Medicare guarantee. In a brainstorming session with top aides, he said he’d been thinking about his recent trip to Chile.

“I’m going to other parts of the world and they’re showing me tremendous investments in infrastructure and innovations in education,” Obama told them. “They’re willing to spend money on that. The Republican budget reflects a fundamental pessimism. It says that to get the deficit in line, we can’t afford to be as visionary as these countries, and we can’t be optimistic because they’re not willing to let an extra penny come from high-income people.” Smaller nations were aiming bigger.

Obama had a lot of pent-up passion. He’d just come through weeks of brutal budget negotiations that had resulted in $38.5 billion in cuts. Now, with a government shutdown averted, Obama felt the time had come to get tough. He wanted to draw lines and call out the Republicans.

The speech he gave on April 13 slammed the GOP for painting a downer picture of the country’s future: “It’s a vision that says if our roads crumble and our bridges collapse, we can’t afford to fix them. If there are bright young Americans who have the drive and the will but not the money to go to college, we can’t afford to send them…Worst of all, this is a vision that says even though Americans can’t afford to invest in education at current levels, or clean energy, even though we can’t afford to maintain our commitment on Medicare and Medicaid, we can somehow afford more than $1 trillion in new tax breaks for the wealthy. Think about that.”

Republicans were irate—and nervous. The president was aiming to gain the high ground in the values war, and this blast was far sharper than any he’d fired in a long while. But then Obama’s assault evaporated. Within the White House, the order came down from on high: Tone down the rhetoric until we make a deal to lift the debt ceiling.

Some Obama-ites were in a more pugilistic mood. The speech had struck the right note, a former senior adviser told me later: “Why not repeat that five times? Emphasize why we won’t cut off the vulnerable, why government investment is important. Why not follow up over and over?” Austan Goolsbee, then chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, had produced a whiteboard video explaining what was wrong and excessive about the Ryan budget, but the White House decided not to release it.

Obama and other aides were worried about a financial meltdown if the debt ceiling was not raised. David Axelrod, Obama’s message guru, told me, “The decision was made to allow the negotiations to proceed until the president needed to intervene.” As Robert Gibbs put it, “It’s difficult to put out your right hand to shake their hands and then strike them with your left hand.”

This fit a pattern that had long disappointed (and, at times, enraged) congressional Democrats and grassroots activists: Obama would proclaim his progressive inclinations and then trade in the soaring rhetoric for negotiations that yielded uninspiring compromises. Many of the president’s supporters wondered: What was he doing? Why not consistently pummel the tea partiers on the Hill if he truly wanted a fight over values?

For most of the past year, I have been investigating what makes the Obama White House tick, conducting scores of interviews with past and present administration officials for my forthcoming book, Showdown. The overarching tale that emerged was that while the third year of Obama’s presidency did not produce outcomes sufficient for frustrated liberals, it did mark the end of the compromiser-in-chief. Through the budget fight and then the debt ceiling dustup, Obama and his aides felt constrained by their responsibility to prevent the economic damage a shutdown or debt freeze would cause. They had to negotiate with hostage takers, some of whom were willing to shoot the hostages. But once the debt ceiling crisis was resolved, that changed.

Days after the compromise was announced, Obama called Gene Sperling, his top economic adviser, into his office. Bring me a major jobs plan, he said. By next week. The latest employment numbers were frightening; it seemed that the anemic recovery could be stalling out. Though chief White House strategist David Plouffe and communications director Dan Pfeiffer worried about pitching a pricey initiative, in Oval Office meetings Obama demanded a jobs package that would make a difference.

In one of these discussions, Obama asked Sperling, “Put Congress and politics aside. If you were trying to fix the economy, what would you do?”

Spend money to help states hire and retain teachers, Sperling said. This would help preserve consumer demand in the short term and prevent the education system from deteriorating and becoming a drag on the nation’s future.

Why isn’t that in the plan? Obama asked.

Republicans won’t pass it, Sperling said.

Let’s decide what we believe is best, Obama said. Vice President Joe Biden savvily suggested adding police officers, firefighters, and other first responders. At another meeting—after the bill for Sperling’s jobs plan had crept up from $350 billion to about $450 billion—Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, who was usually Mr. Fiscal Discipline, backed up Sperling. Plouffe agreed that the larger price tag would make the plan harder to sell, but he noted that it would illustrate the bold difference between the president and the Republicans.

In early September, Obama unveiled the jobs plan during a speech to Congress that picked up where his anti-Ryan address had left off. Perhaps the most powerful moment came when Obama asked: “Should we keep tax loopholes for oil companies? Or should we use that money to give small-business owners a tax credit when they hire new workers? Because we can’t afford to do both. Should we keep tax breaks for millionaires and billionaires? Or should we put teachers back to work so our kids can graduate ready for college and good jobs? This isn’t political grandstanding. This isn’t class warfare. This is simple math.”

Obama was dishing out, as could be expected with him, a calm sort of populism: There’s a rational choice to be made, and there’s only so much money. But he was also delivering a strong defense of government—a perspective that had been overwhelmed by the tea party’s starve-the-beast message. “We no longer had a gun to our head,” a senior administration official recalls. Following the debt ceiling mess, the president had concluded that he could no longer work the inside game with Republicans held captive by the extreme ranks of their own party.

Obama was done being the above-the-fray president, the reasonable fellow who would ease the bickerers of Capitol Hill into compromise. He and his aides had once believed that image was critical to winning over independent voters. Now they had concluded that if Obama pursued substantive compromises but failed (because House Speaker John Boehner could neither control nor defy his tea party wing), he would appear ineffectual. “There was no pot of gold at the end of the adult-in-the-room rainbow,” says one former top administration official, “and there were only so many times Lucy could pull away the football.”

Republicans said no, no, and no to the president’s jobs package, but this time Obama didn’t throttle back. He plugged away at event after event—mostly in 2012 swing states—offering various either/ors. The nation could invest more in infrastructure and compete with the Chinese, or tax cuts could be preserved for the wealthy. America could protect Medicare or tax breaks for corporations. He would still tick off liberals (killing tighter smog regulations; allowing restrictions on the morning-after pill), but on the economy, he was finally doing what some of his allies had long urged.

In early December, Obama flew to Osawatomie, Kansas. In this small town in 1910, President Teddy Roosevelt, by then out of office but still deeply involved in politics, delivered a rip-roaring speech defining a “New Nationalism.” Perhaps the most radical address ever given by a US president, it declared that the “citizens of the United States must effectively control the mighty commercial forces” and called for a “square deal” for workers, including rigorous government regulation of the workplace and Big Finance. It was denounced at the time as “communistic,” “socialistic,” and “anarchistic.”

Obama didn’t go nearly as far as T.R. But he did talk about the “raging debate over the best way to restore growth and prosperity, restore balance, restore fairness.” He said this was “a make-or-break moment for the middle class and for all of those who are fighting to get into the middle class.”

Noting that the United States had become a nation of greater economic inequality—Obama and his aides had been watching Occupy Wall Street’s message catch on—he returned to the vision he had presented in his 2011 State of the Union. To revive a strong middle class, Americans must join together, through government, to educate, innovate, and build.

“This isn’t about class warfare,” he said. “This is about the nation’s welfare.” Afterward, Jim Messina, Obama’s campaign chief, sent out an email to supporters proclaiming that this approach “will inform every discussion we have with undecided voters over the next year.”

Two weeks later, the House Republicans helped make Obama’s point for him: They refused to go along with a bipartisan Senate compromise to extend unemployment benefits and the payroll tax cut for two months. But Obama now felt emboldened to confront GOP obstructionism, and the Republican leadership blinked; Boehner ended up embarrassingly losing this game of chicken. Soon afterward, the president would issue a recess appointment for Richard Cordray to head the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—in defiance of Senate GOP filibusters. And in a feisty State of the Union speech in January, he laid out the choice: “We can either settle for a country where a shrinking number of people do really well while a growing number of Americans barely get by, or we can restore an economy where everyone gets a fair shot.” At stake, he added, was nothing less than “American values.”

Obama’s new tack did seem to yield political dividends. By late 2011, he scored better than Republicans when poll respondents were asked whom they trusted to handle the economy and even the deficit. Plouffe could barely believe it—he told people it was as if the Republicans were ahead on the issue of children’s health care. A core GOP strength had been neutralized.

Yet as they looked to 2012, Obama and his advisers had one key number in mind: No president since FDR has ever won reelection with unemployment greater than 7.2 percent. If the election evolved mainly into a referendum on Obama’s economic policies, he would be in deep trouble. But if he and his team could shape it as a choice between two sharply distinguished sets of values, he would have a fighting chance.

The first year of Obama’s face-off with the tea-party-controlled House had been ugly. The president had not achieved his main policy objectives. But as he and his inner circle saw it, he had managed to lay the foundation for the decisive campaign to come—and had found his fighting groove. In the face of unremitting opposition, perhaps because of it, Obama realized much of his strategic plan. He could only hope the same would happen in 2012.