Flickr user <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/maynard/100749600/sizes/l/in/photostream/">Nemo's Great Uncle</a> / Creative Commons

I’m thrilled that my phone contract is up in February. I’ve been coveting the iPhone, which will be a welcome change after two years of toting around a clunky, barely web-enabled dinosaur. But when I upgrade to a smart phone, what will become of my dopey old dumb phone?

This very question is the subject of the The Story of Electronics, the latest installment of sustainability expert Annie Leonard‘s engaging Story of Stuff Project. The eight-minute film explains that today’s consumer electronics are “designed for the dump”: After about two years, most gadgets are either obsolete or broken, and they’re usually cheaper to replace than to repair. Technology is advancing at so fast a pace that every two years, the number of transistors placed on a circuitboard doubles, increasing computer memory and processing speed. (This continuing trend was first noticed in the late 1960s and is called Moore’s Law.) Until that rate slows, or manufacturers begin to make cell phones with standardized replaceable parts, you’ll still have to get a new phone every two years just to keep pace with technology.

More than 130 million cell phones in the US alone are retired every year, the USGS estimates. Not great news for the planet, considering phones contain substances harmful to humans and the environment, like cadmium, lead, and beryllium (all carcinogins), as well as arsenic. So what’s the best way to make sure your old phone’s not leaking chemicals into the ground?

Most major wireless carriers participate in “take-back” programs, which allow you to send your dead phone back where it came from for free—or sometimes even a cash rebate. Once a cell phone arrives at a take-back facility, if it’s still workable and a relatively recent model, it’s likely going to get refurbished and resold, either on the consumer market or to a charity. (Verizon’s HopeLine program, for example, donates phones loaded with 3,000 free minutes to domestic violence victims.) Other refurbished phones are sold in Latin America and Africa, to people who don’t mind using a secondhand, behind-the-times phone.

If your phone is really kaput, it will either get broken down and sold for parts or passed on to a smelter, where the entire phone is melted down and the liquids are separated to be reconstituted. (This process is sometimes called “above-ground mining.”) Smelters harvest the little bits of valuable metals (gold, copper, iron, silver, zinc, nickel, platinum, tin) used in the circuitboards and soldering. In one metric ton of old cell phones without batteries (about 8,800 individual phones), there’s an estimated 308 pounds of copper, 7 pounds of silver, and half a pound of gold. The smelting process, also used to melt down recycled aluminum cans, does generate some greenhouse gases and slag (the discarded silica and metal oxides used to isolate liquid metal). But overall, the environmental and monetary costs of smelting down existing metals are lower than mining, transporting, and refining new ore. For example, one ton of gold ore only contains .18 ounces of pure gold, while there’s about 40 times that amount in one ton of cell-phone circuitry.

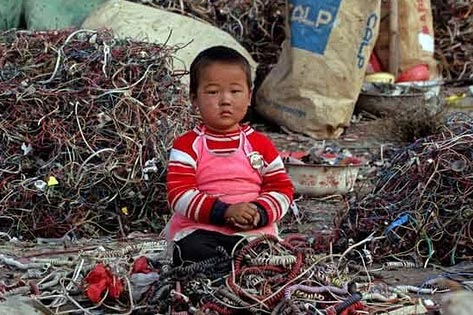

Breaking cell phones up and separating the parts is the process that most people are leery of. Annie Leonard points out that workers in China and Africa often dismantle electronics’ harmful insides without proper personal or environmental protection: For example, in the town of Guiyu, China, 1.5 million pounds of e-waste are dismantled every year—often by workers without gloves—and leftover junk is disposed of in open fires.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to find out if your cell-phone carrier exports items abroad to be broken, because many of them work with third-party companies—three of which I tried unsuccessfully to contact by, um, telephone. (I did reach a T-Mobile rep who said his company works with a Dallas-based recycler called Touchstone that separates phone components in the US. He also said 70 percent of the phones T-Mobile receives go on to be refurbished.) Newer phones like smart phones may be heavier than old candy-bar-style phones, but they contain a lot more electronics in a smaller package.

The good news: Cell phones are getting more environmentally friendly. Today’s phones are made with considerably less cadmium and lead than older models, and they’re also getting lighter. The average phone weighs around 4 ounces, minus the battery—about half of what it weighed in 2000. Recycling rates are also improving: In 2003, fewer than 1 percent of owners recycled their phones, but now it’s closer to 20 percent. Rep. Gene Green (D-Texas) recently introduced the Responsible Electronics Recycling Act (H.R. 6252). It would outlaw sending e-waste to developing nations, but it’s still hanging out with the House Committee of Energy and Commerce.

You can help minimize waste by opting for a refurbished phone (available through all major carriers) instead of a new one. Once you’re done with your phone, there are a number of recycling systems you can participate in. To reduce the carbon footprint from ground transportation and reclamation, I prefer programs that handle large volumes of cell phones. Best Buy has kiosks in nearly every store where you can drop off your used electronics. The program doesn’t export any non-working phones or components to developing countries, and it requires third-party partners to submit documentation of environmental compliance. If you’re looking to make a few bucks off your phone, check out GreenPhone.com, which gives you cash for your old unit; offers you a free, printable shipping label; and will plant a tree every time you recycle a phone. The folks over at Earth911 recommend this website to see if your local recycling outfit is certified as an “e-Steward”—which requires strict control over exporting overseas, “full accountability for the entire downstream recycling chain,” and disclosure on any airborne toxins released during the smelting process. If none of these float your boat, you can see an extensive list of drop-off and mail-in recycling programs at the EPA’s eCycle site.

Got a burning eco-quandary? Submit it to econundrums@motherjones.com. Get all your green questions answered by visiting Econundrums on Facebook here.