Flickr/<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Voting_in_Hackney.jpg">Alex Lee</a>

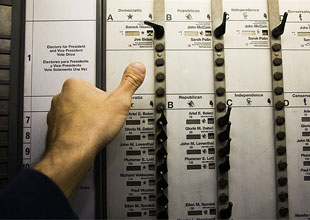

In Houston, conservative poll watchers have been accused of hovering over early voters as they’ve tried to cast their ballots. The same complaints have surfaced in North Carolina’s 13th Congressional District—home to Raleigh and other major cities—where poll watchers have been accused of taking down voters’ names and addresses. In Indiana’s Marion County, an altercation erupted after a local Republican official was taking photos of voters in violation of election law. There’s a common thread connecting these and other recent election episodes—they’re concentrated in communities with significant minority populations where tight races are on the line.

Even before Republicans and tea party activists began stirring up voter fraud fears this year, Democrats worried that many of the minority and first-time 2008 voters who showed up in record numbers at the polls in 2008 might sit out the 2010 midterms. In recent weeks, a rash of allegations of voter intimidation during early voting has raised concerns that the voter fraud crusade could make their turnout troubles even worse.

Anti-voter-fraud campaigns are popping up across the country, but their biggest rollouts have tended to be in lower-income areas with large minority populations. “Turning out people in those communities is often difficult because their priorities lie elsewhere,” says Gerry Hebert, executive director of the non-partisan Campaign Legal Center. “Consequently, it’s a concern when word gets out about people encountering difficulty at the polls—it makes it doubly hard to get voters out.” He says that such anti-fraud campaigns could have a “chilling effect” on turnout. Already, the Department of Justice is investigating complaints about voter intimidation in Houston, raising concerns that overzealous poll watchers will overstep their bounds—particularly as conservative organizers urge them to use legally dubious poll-watching tactics.

On the left, there’s particular concern that Latino voters might not turn out in large numbers: They’re one of the Democratic-leaning groups with the lowest enthusiasm about voting this year, in part because of President Obama’s failure to fulfill his promises on immigration reform. And it might not take anything more than an environment of voter fraud paranoia to make Latinos even less inclined to show up, voting rights advocates say. “It doesn’t require anyone to show up in any precinct to engage in any actual activity—it creates a climate of suspicion that could get some number of people and dissuade them from turning out to vote,” says Dale Ho, assistant counsel for the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund. Moreover, the anti-immigrant backlash that emerged in the wake of Arizona’s harsh immigration law has also raised concerns that ethnic minorities and immigrants could be unfairly scrutinized by fraud-spotters at the polls.

Voter-fraud activists insist that they’re committed to stamping out electoral crimes regardless of racial background or party affiliation. The organizers of Election Integrity Watch—a conservative and tea party-led anti-fraud effort in Minnesota—bristled at the notion that their campaign might suppress the minority vote. “The idea that Election Integrity Watch would deter minorities from going to the polls is a racist idea,” says Dan McGrath of Minnesota Majority, a group supporting the statewide anti-fraud effort. “Those who make such suggestions must believe that minorities are more likely to engage in illegal voting.” Just the same, supporters of McGrath’s group and others often trot out illegal immigrants and the New Black Panthers as prime examples of voter fraud villains.

Minnesota’s Election Integrity Watch has urged activists to question voters’ citizenship and wear buttons that say “Please I.D. Me” to the polls—even though the state doesn’t require voters to show photo identification. Civil rights advocates insist that such efforts ultimately single out minority voters for heightened scrutiny. “When allegation of fraud are linked to citizenship and immigration, it’s quite clear that the target is the Latino community,” says Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, adding that many Latinos are first-time or irregular voters who are generally more easily deterred from voting.

As voter-fraud hysteria mounts, Democrats and their allies are trying to sound the alarm about potential voter intimidation and suppression—partly to warn supporters that their rights might be trampled upon, and partly to paint the opposition as paranoid and overzealous. But highlighting these tactics has a downside: in drawing attention to problems that could arise at the polls, Democratic officials and voting rights advocates also run the risk of overhyping potential intimidation—and deterring even more voters from showing up.

“If we yell too loud about it, it helps them create the sense that the polling place is a dangerous place to be,” says Matt Angle, a Texas Democratic strategist who’s aiding get-out-the-vote efforts in the state. Vote suppression “should be tracked, monitored, and publicized when it occurs. But maybe not so much anticipatory hand-wringing—it just makes matters worse,” says Gary Segura, a political science professor at Stanford University who runs the polling firm Latino Decisions.

Instead of raising the alarm bells about all the things that could go wrong, officials and advocates should do what they can to send the message that “by and large voting is easy,” says Eric Marshall of the Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which offers a national hotline for voters who have questions or problems at the polls.

And while vote suppression could have an impact in certain parts of the country, minority advocates warn that Democrats also shouldn’t use conservative voter fraud campaigns as an excuse if voter turnout is low. The right’s voter fraud crusade “createss this air of illegitimacy, feeding on hostility, contempt, and alienation,” says Segura, the pollster. “But it’s hard to feel bad for the Democrats—they’ve delivered almost nothing to core Democratic constituency groups. If there is low turnout, is Republican intimidation to blame…or Barack Obama?”