Robert McNamara’s middle name was Strange—and the former defense secretary, World Bank president, and Ford executive certainly leaves behind an unusual and complicated legacy. Most of all, McNamara, who died this morning at the age of 93, will be remembered as one of the chief architects of the Vietnam War, a conflict—known to many as “McNamara’s War”—with which he became synonymous. An intensely private man, he refused to address the war and his own doubts about its prosecution for decades, though he eventually ruminated on his misgivings and mistakes in his 1995 memoir, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. Years later, it was a haunted McNamara who appeared in Errol Morris‘ acclaimed documentary, The Fog of War. His apparent contrition never silenced his critics, though, who considered him a war criminal whose mea culpa was too little too late.

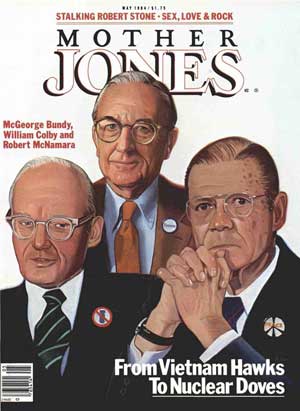

In 1984, Mother Jones ran a cover story [PDF] by David Talbot, who would later found Salon.com, on the transformation of McNamara, former National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, and ex-CIA chief William Colby from Vietnam-era hawks to advocates of a nuclear weapons freeze. Talbot described McNamara as “the cost-control wizard who thought the war could be run like a Ford assembly line: body counts, kill ratios, bombing raids. And when he saw that it wasn’t adding up, that it did not compute, he repeatedly lied—to Congress, to the press, to the American public.”

At the time, McNamara bristled when Talbot questioned his motives for speaking out on nukes.

McNamara was even briefer when I asked him how he would respond to those who assert he is trying to reclaim his virtue by speaking out against the nuclear arms race. “That’s their opinion,” he said icily. Shortly afterward, he let me know our interview was over.

As Talbot reveals, McNamara was even an enigma to his only son, Craig, who protested the war his dad prosecuted. He writes:

Craig’s relationship with his father today seems full of complexity. He strongly wants to embrace his father’s new peacemaker persona but says that his father’s line on the nuclear freeze “puts me on guard.” (McNamara says he heartily approves of the freeze movement but finds the actual freeze proposal “overly simplistic.”) He wants to understand what his father went through during Vietnam but is denied this kind of access to his father’s inner thoughts (though he is McNamara’s only son).

“There has got to be a lot of guilt and depression inside my father about Vietnam,” says Craig, who, with the trademark McNamara wire-rim glasses, looks like a young, soft-featured version of his father. “But he will not allow me into the personal side of his career. I’ve thought long and hard about this, about what tack to take with him. But my father has a strong sense of what he will and won’t talk about with me. I would ask him things like why he left the Pentagon in ’68. I felt I could learn a tremendous amount of history from him. And I felt I could teach him about the peace movement. But he just gives these quick 30-second responses and then deflects the conversation by asking, ‘So how many tons did you produce on your farm last year?'” Still seeking refuge in statistics.

And yet Craig is still his father’s son, even his progressive activism in some ways a product of McNamara’s philosophy. “He always pushed me to be a political person. He instilled in me a deep sense of giving back to the world what it gives to you.” Before McNamara the computer-minded warrior, of course, had come McNamara the Ford executive who once made a speech—against company orders—declaring that there had to be a higher calling for businessmen than simply making money. And after Vietnam had come McNamara the international aid czar, who put more emphasis on helping the poorest developing countries than did his predecessors at the World Bank. Robert McNamara remains the embodiment of American liberalism, with all its lights and shadows.

Whatever your views on McNamara, he unquestionably left his mark on history. May he rest in peace, even if his legacy doesn’t.