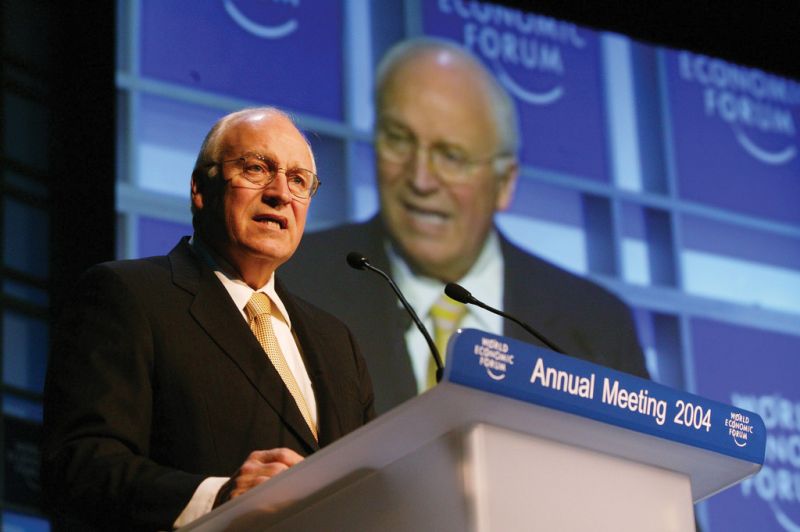

Update (7/10/2015): Yet another report, this one based on a seven-month investigation requested by the board of the American Psychological Association, has confirmed the allegations in the April report below, and goes into more depth on the APA’s complicity in the CIA’s torture program. The New York Times, which obtained an early copy, offers details: “The report concludes that some of the association’s top officials, including its ethics director, sought to curry favor with Pentagon officials by seeking to keep the association’s ethics policies in line with the interrogation policies of the Defense Department, while several prominent outside psychologists took actions that aided the CIA’s interrogation program and helped protect it from growing dissent inside the agency.” Read the rest here.

Update (4/30/2015): A damning new report, “All The President’s Psychologists,” claims that the American Psychological Association collaborated directly with the Bush administration to bolster its ethical and legal justifications for America’s torture program. You can read all about it in the New York Times. But long before that, award-winning reporter Justine Sharrock was digging up the inside story of the complicity of doctors, psychiatrists, and psychologists in the torture, and the failure of those professions to take action against their colleagues—who broke their professional oaths in the most egregious of settings.

****

THE MEMORY OF detainee No. 173379 still haunts Andrew Duffy. The 24-year-old prisoner showed up in March 2006 among a truckload of captures at Abu Ghraib, where Duffy was stationed as a medic. His job was to treat new arrivals in an overcrowded, sweltering tent suffused with the stench of human waste and vomit. There, Duffy, then 19, handled everything from common diseases like tuberculosis to festering gunshot wounds.

But the new prisoner stood out. He was belligerent, yelling gibberish and staggering like a drunk. Having witnessed this kind of behavior before with detainees in diabetic shock, Duffy checked the man’s blood-sugar level. From 70 to 140 milligrams per deciliter is normal; his read 431. The prisoner explained that Iraqi soldiers had held him for five days without his insulin. Duffy called the compound’s hospital to request an immediate transfer. It was denied. Duffy’s medical supervisor ordered him to just give the guy water.

He was used to this. The prison’s medical officers routinely rejected medics’ requests to hospitalize sick and wounded detainees; the general sentiment, Duffy says, was “screw these guys.” Once, he tried to revive an elderly prisoner whose heart had stopped. The ambulance’s defibrillator had the wrong pads, so Duffy attempted CPR and mouth-to-mouth. “Why did you make out with that hajji?” the hospital staffers taunted. “Why didn’t you just let him die?” For the next month, he heard it around the chow hall: “That fucking medic gave that hajji CPR!”

Beyond patching up detainees, Duffy and his comrades with the 134th Medical Company of the Iowa National Guard were ordered to soften them up for interrogation. One day, Duffy and an MP restrained and hog-tied a resisting detainee—cuffing his wrists to his crossed ankles behind his back—so that Duffy could check his vital signs. Guards later boasted that they’d left the man that way for 12 hours.

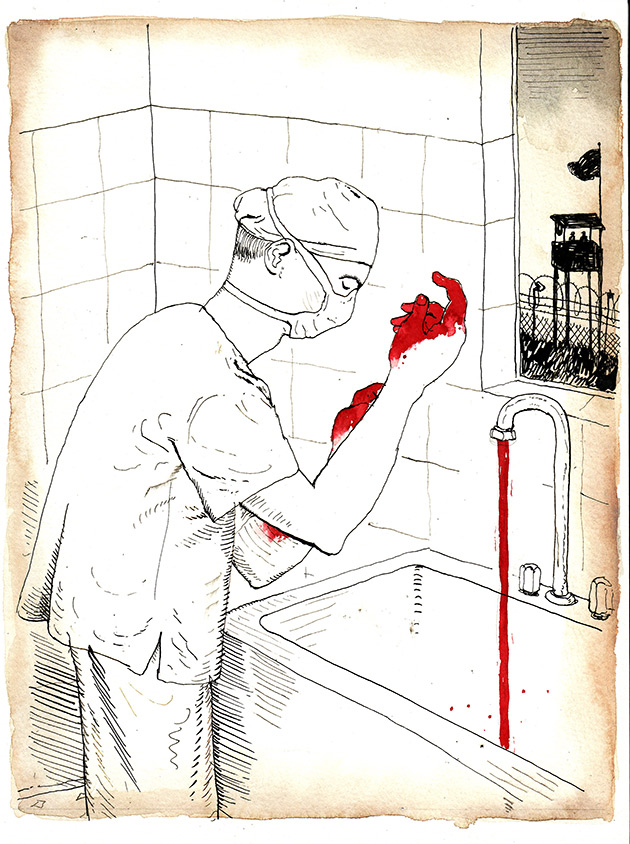

Throughout Duffy’s year at Abu Ghraib—long after the infamous photos were published and the Pentagon vowed that detainees were no longer abused—men were still being strapped into restraint chairs and left in the blazing sun for hours or locked in cells too small to lie down in for 24 hours at a time. The medics regularly found prisoners dehydrated, wrists bloody from overtight handcuffs, ankles swollen from forced standing, joints dislocated from stress positions. They knew to keep their written evaluations vague, never mentioning cause of injury as a standard medical report would. When they shuttled broken detainees to and from the prison’s interrogation rooms, the orders were explicit: Transport only. No medical care. No paper trail. Flouting the Geneva Conventions, Duffy’s platoon sergeant even ordered the medics to strip their uniforms and ambulances of the Red Cross emblems that denoted them as noncombatants. Should anyone from the Red Cross show up to see the prison, the soldiers were told, send them away and tell them nothing.

FOR MORE THAN five decades, starting with the prosecution of Nazi doctors during the Nuremberg trials—seven were sentenced to death—the Pentagon made a point of ordering its physicians to abide by international norms. The World Medical Association, which counts the American Medical Association (AMA) as a member, had issued clear directives: Doctors could not assist in torture or cruelty of any kind, and were duty bound to report abuses they witnessed. The United Nations later clarified that the rules apply to all medical personnel—from surgeon to nurse to psychologist to lowly medic. Even now, the Army’s Military Medical Ethics textbook echoes the Geneva Conventions, noting that a doctor-warrior’s priority is always “physician first.” “They don’t give up their licenses and their medical ethics when they join the military,” explains George Annas, a professor of law and public health at Boston University.

But even as the nation debates disbarment for the Bush administration lawyers who green-lighted torture, the medical profession has dealt reluctantly, if at all, with its own involvement. “The indifference is shocking,” says retired Army Brig. General Stephen N. Xenakis, a rare outspoken critic among military doctors. “Some civilian doctors are appalled, but many say, ‘It doesn’t affect my life; I’m not involved.'”

Doctors were complicit in the torture strategy from the start. In December 2002, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld issued a directive allowing interrogators to withhold care in nonemergency situations—men with injuries including gunshot wounds were denied treatment as a way to make them talk. (The directive was soon revoked, but the practice continued.)

Four months later, Rumsfeld ordered that doctors had to certify prisoners “medically and operationally” suitable for torture and be present for the sessions. At Abu Ghraib, interrogations had to be preapproved by a physician and a psychiatrist. “They have the final say as to what is implemented,” Colonel Thomas M. Pappas told military investigators.

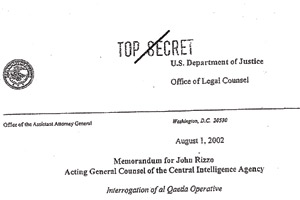

The CIA received similar advice in 2002 and 2005 from the Justice Department, whose torture memos recommended that physicians and psychologists be present for the interrogation of “high value al Qaeda detainees.” These doctors, the lawyers argued, would see to it that interrogators didn’t torture detainees by intentionally inflicting “serious or permanent harm.”

But it was in June 2005 that the Pentagon delivered its biggest ethical bombshell, a memo that allowed doctors to participate in torture and share medical records with interrogators so long as the detainee in question wasn’t officially their patient. The directive’s author, physician and top Pentagon health official William Winkenwerder Jr., received a prestigious award from the AMA that year for outstanding contributions “to the betterment of the public health.”

Field medics like Duffy, who were still being trained to do no harm according to the military’s old ethical standards, faced a rude awakening on the ground. “You have all these codes you follow as a health care worker, but then it’s, ‘Now we’re in Iraq, forget those,'” Duffy told me.

Plenty of doctors in uniform felt similarly but, like Duffy, did as they were told. A 2007 Red Cross report indicates that CIA medical personnel presided over hundreds of waterboardings, including those of Abu Zubaydah and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. One Al Qaeda associate, an amputee named Walid bin Attash, told the Red Cross that health workers periodically measured the swelling in his remaining leg as he was shackled in a stress position at a CIA black site. Gitmo military doctors twice sent alleged 9/11 planner Mohammed al-Qahtani to the hospital after his heart rate fell to dangerously low levels, only to send him back to the torture chamber when he improved.

Aware of the breaches, Xenakis says, a few military physicians called for ethical reviews. But the Pentagon overruled them, and the protests ceased. “There was a blackout,” he explains. Fearing for their careers, “military doctors wouldn’t speak, even informally.” Before long, adds M. Gregg Bloche, a Georgetown University law professor who interviewed military physicians on condition of anonymity, the Defense Department was screening doctors and deploying only those on board with the program.

DURING THE 1980s, as a symbolic show of support for doctors working under oppressive regimes, the American Medical Association enacted guidelines that forbade their participation in torture. But even when it became clear that US doctors were violating these rules, the association (which represents a quarter of a million doctors and med students nationwide) took no steps toward censuring its wayward members. Instead, in 2004, it released a statement pointing to its existing guidelines. The AMA’s refusal to take a stronger stand, says Penn State bioethics professor Jonathan H. Marks, has been “a source of shame” for the profession.

What stood out for Steven H. Miles, a bioethicist at the University of Minnesota Medical School, was the association’s resounding silence in February 2006, after the UN Commission on Human Rights condemned American doctors for having “systematically” participated in detainee abuse. “In a serious medical community, that would be a call to arms,” Miles says. “But the AMA said nothing.”

It wasn’t until November 2006 that the association issued a statement clarifying that doctors cannot participate in interrogations of any kind. Xenakis, who helped shape the new policy, says most of the AMA’s military delegates resisted the move, arguing that “the mission of getting information was greater than the medical ethics they acknowledged we were overriding.” (The four military delegates contacted for this story declined to comment.)

The nation’s top medical association has all but ignored the sorts of serious ethical breaches that Duffy witnessed daily—the neglect, the filthy conditions, the incomplete medical reports. Some doctors even abused detainees under the guise of treatment. Brandon Neely, who served as a guard at Guantanamo back in 2002, twice watched a Navy physician perform violent exams on new arrivals. Without lubrication, he said, the doctor “just reached back and shoved his finger as hard as he could in the rectum.” His fellow MPs told him the other doctors were doing the same thing. They all heard the prisoners screaming.

On at least four occasions, doctors have petitioned AMA leaders to endorse an independent investigation of their colleagues’ role in the abuses—only to be voted down. “They said, ‘Look, we trust our military and we aren’t going to step on their toes,'” explains Matthew Wynia, director of the association’s Institute for Ethics.

None of the AMA’s top officials would be interviewed for this story. When pressed on why they were so reluctant to act, even after the complicity of doctors became apparent, spokeswoman Kate Cox insisted that the association has no specific knowledge of doctors being involved in abuse or torture and that it is not equipped to conduct the sort of investigation needed to “credibly confirm” such allegations. Besides, Cox said, the AMA has fulfilled its duty simply by setting ethical standards.

But the AMA’s critics worry that its half-measures have already—perhaps irreparably—damaged the moral standing of American doctors. “It has had a corrosive effect,” says Xenakis. Adds Miles, “We’re now in an extremely poor position to protest abuse in other countries. It will silence us as a medical community.”

MENTAL HEALTH practitioners were, if anything, even more deeply involved in the abuses. In November 2002, Gitmo commander Maj. General Geoffrey Miller put together a Behavioral Science Consultation Team, a group of psychiatrists and psychologists tasked with preparing prisoner profiles and advising interrogators on the use of environmental manipulation, sleep deprivation, exploitation of individual fears, and other coercive methods.

Among the practitioners was Guantanamo senior psychologist Major John Leso, who helped plan and implement the 50-day interrogation of Mohammed al-Qahtani. Detailed logs of the torture sessions indicate that the prisoner was sexually humiliated, isolated and deprived of sleep for extended periods, subjected to extreme cold, shackled in stress positions, tormented by military dogs, and leashed and made to perform like a dog.

Leso, who was in the interrogation room for part of Qahtani’s ordeal, advised—among other things—that the detainee could be disoriented by spinning him on a swivel chair so that he couldn’t fix his eyes on one spot. Along with the prison’s medical doctors, he regularly evaluated Qahtani for his ability to tolerate further abuse. During one session, the medical staff injected the prisoner with three and a half IV bags of saline—Qahtani’s questioner then wouldn’t let him urinate until he provided satisfactory answers. Despite evidence of Leso’s actions, the American Psychological Association has failed to act on an ethics complaint by a fellow APA member.

Rank-and-file psychologists are deeply divided on the subject of torture. In 2005, an association task force (six of its ten members had military ties) voted to condemn torture but still allow psychologists in the interrogation room, where, its members argued, they might discourage abuse and even save detainees’ lives. Incensed, thousands of psychologists petitioned for a vote on the question by the APA membership. In a roughly 60-40 tally, the association decided that psychologists have no place in the interrogation room. (For more on the APA and torture, see David Goodman’s “The Enablers“.) It was the right choice, says Robert Jay Lifton, a psychiatrist and former military medic who has written about the role of Nazi doctors during the Holocaust. Putting health professionals into an abusive setting, he argues, “can confer an aura of legitimacy and can even create an illusion of therapy and healing.”

Which is more or less what Duffy experienced. “If a medic was around, there was a sense of some control,” he told me. “The guards probably thought, ‘If I really cross the line, this guy would stop me.'”

In May 2006, the American Psychiatric Association, which represents some 38,000 psychiatrists, reiterated its past position that its members should not directly assist in interrogations. But Steven Sharfstein, then the association’s president, also noted that psychiatrists “wouldn’t get in trouble” if they heeded military orders over the association’s advice—which, he added, should not be considered “an ethical rule.”

IT’S NOT THAT the medical community lacks the tools to police itself. Doctors can’t practice without a state license, and a grave breach of ethics can cost them that license. State licensing boards are legally obligated to investigate violations, yet no state medical board has ever disciplined a doctor for assisting in military torture.

One California complaint illustrates the boards’ reluctance to confront the military. Filed by New York-based attorney Scott Sullivan on behalf of four former detainees, the 2005 complaint targeted Captain John S. Edmondson, then Guantanamo’s lead physician. The men claimed that their medical records were shared with interrogators, who then withheld treatment for heart problems, worms, constipation, and injuries inflicted by the camp’s “internal reaction forces”—five-man teams dispatched to beat recalcitrant prisoners. When these attackers showed up, the detainees claimed, medical personnel would instruct them on details such as, “Hit him around the eye; don’t poke him in the eye.

But the complaint never got a hearing: The Pentagon claimed jurisdiction in the case, and the medical board demurred. Citing insufficient subpoena power and resources, it turned the matter over to military investigators, who found no evidence of wrongdoing. “The board didn’t care how they got out of it,” says Sullivan. “They just didn’t want to be in the middle of a hot-button political issue.”

Mother Jones obtained three similar complaints filed by former APA member Trudy Bond against psychologists who allegedly participated in abuses. In addition to targeting Leso’s license in New York, she pursued his Gitmo colleague, senior psychologist Colonel Larry C. James, in Louisiana. In Alabama she filed a complaint against Diane M. Zierhoffer, a military psychologist who helped direct the interrogation of an Afghan teenager accused of throwing a grenade at a US military vehicle. Zierhoffer recommended a month of isolation, which can cause or exacerbate mental health problems; later, the teen tried to hang himself.

None of these complaints resulted in disciplinary action. Licensing boards, says bioethicist Marks, are “reluctant to call into question anything with broader implication beyond the individual physician, especially if it is impugning government officials or state policy.”

Absent action from the profession, some states have turned to political pressure. California’s Senate passed a symbolic joint resolution last year urging the state’s licensing boards to warn doctors that they could be prosecuted for participating in torture. (The American Psychiatric Association petitioned unsuccessfully to have psychiatrists exempted.) A bill under consideration in New York would bar any health care worker from participating in torture or “improper treatment,” as defined by international standards. But reform advocates say legislation is no substitute for sanctions by doctors themselves. “The practice of medicine,” says Boston University professor Annas, “is something the profession defines and the profession has to guard.”

BACK AT ABU GHRAIB, Andrew Duffy was in no position to disobey a direct order, so he did as he was told and gave water to his diabetic prisoner. By the next morning, detainee No. 173379 was even weaker and more confused. Duffy and his partner again called for a hospital transfer—their third try—and again the captain denied the request. This time, she told them to administer saline through a 14-gauge needle.

That’s a huge needle—more than two millimeters in diameter. A civilian doctor would only use it for extreme trauma situations, with an unconscious patient or with a local anesthetic to numb the pain. At Abu Ghraib, the large needles were used as punishment, or to discourage detainees from asking for care.

A day later, the Army’s criminal investigation unit summoned Duffy and his partner for questioning. No. 173379 was dead. Interpreting his symptoms as insubordination, MPs had pepper-sprayed the man and stuck him in a tiny cell in the scorching heat. Duffy says he filled out a five-page sworn statement, but his captain gave a conflicting account, and the case was dropped. Later, when it became clear that the dead man had been an associate of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the bloodthirsty commander of Al Qaeda in Iraq, soldiers came up to congratulate the medics.

Duffy did what he felt he could. Beyond his statement (which the investigators now claim they have no record of), he complained to his superiors about the shoddy medical supplies and the stripping of Red Cross emblems. More recently, he filed complaints about his platoon sergeant and captain with the Army Inspector General’s office, but nothing has come of it. In any case, much of the paper trail that might have implicated them is probably lost. When the military abandoned Abu Ghraib in September 2006, Duffy and his comrades were given one last order: Burn all of the compound’s medical records.

Correction: It was in 2005 that the American Psychological Association’s task force voted to condemn torture but still allow psychologists in the interrogation room, not in 2007 as originally reported. This story has been updated to reflect the change.