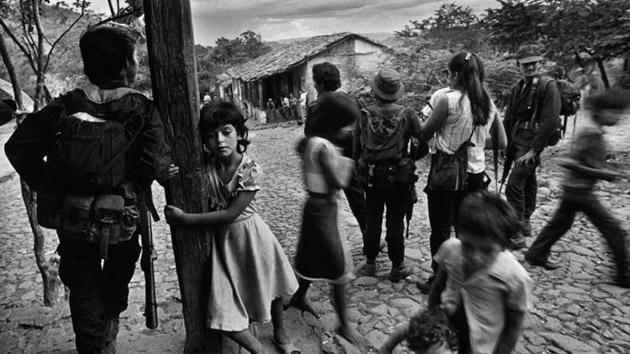

Donna De Cesare

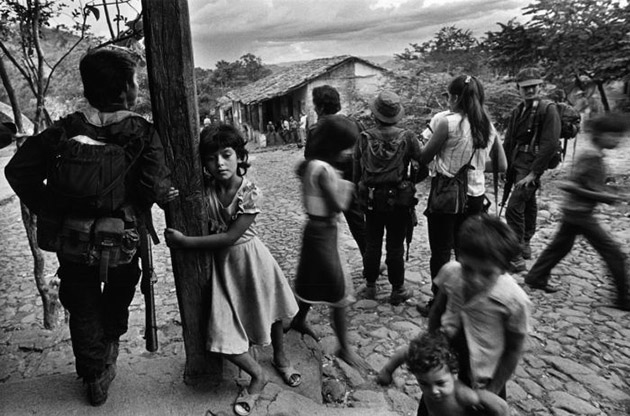

From 1979 until 1992, El Salvador was mired in a civil war that left 75,000 people dead and untold numbers displaced or unaccounted for. It was a conflict marked by extravagant violence: On December 11, 1981, in the mountain village of El Mozote, the Salvadoran army raped, tortured, and massacred nearly 1,000 civilians, including many children. News of the killings didn’t reach the United States until January 27, 1982, the same day the Reagan administration announced El Salvador was making a “significant effort to comply with internationally recognized human rights.” Washington continued to pump aid into the regime—$4 billion over 12 years.

Part of what made the war so complicated, at least for US interests, was the ultimatum it seemed to present: Defeat the guerillas at any cost or lose the country to communism. In the twilight of the Cold War, any threat of a domino effect in the region—Nicaragua had already fallen to the Sandinistas—was too ominous for Washington to bear. By backing El Salvador’s right-wing junta and, by extension, its paramilitary death squads, the United States created a conundrum for journalists: how to document a war whose maneuvers and motivations were kept deliberately murky?

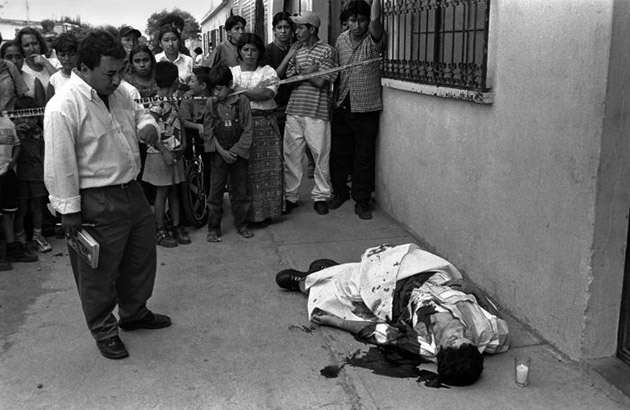

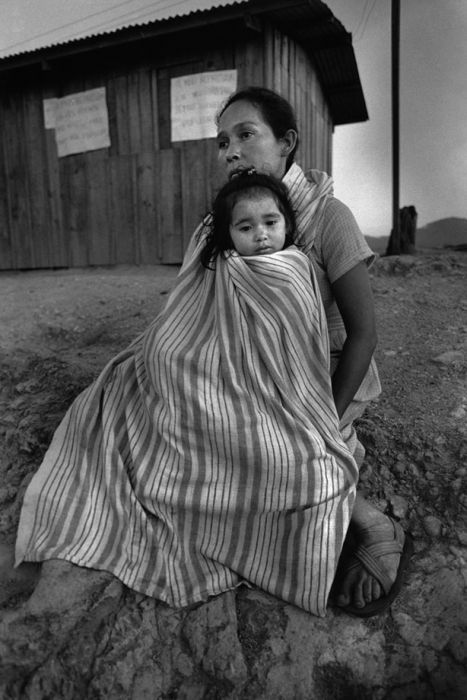

Photographer Donna De Cesare traveled to El Salvador in 1987 to “witness and report on war, with all the earnest idealism and naïvete of youth,” as she puts it in her new photo book Unsettled/Desasosiego. What she couldn’t have known at the time was how the experience would shape the next 20 years of her life. She visited refugee camps in Honduras, Jesuit killings on the campus of Central American University, a morgue in Guatemala City. Her work—like that of Larry Towell and Susan Meiselas—is essential to understanding a chapter in Central America’s history that is too often whitewashed or denied.

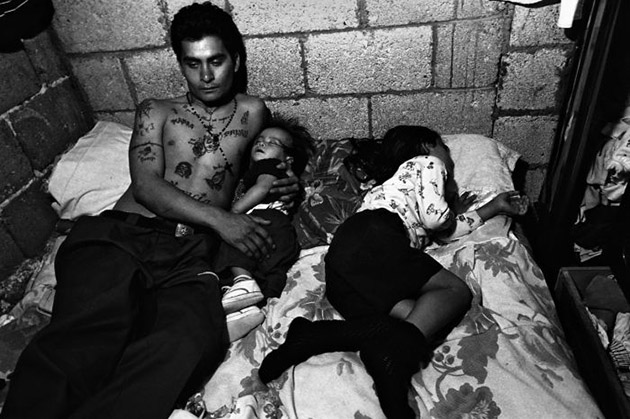

After peace accords were signed in 1992, she shifted her focus to the refugee diaspora in Los Angeles, roaming the tense battleground of the 18th street and Mara Salvatrucha (or MS-13) gangs. There she found an extension and continuation of El Salvador’s turmoil—vigilante justice and honor killings were the rule of law. Gang members broadcast their allegiances via facial tattoos and hand signs, at least until the Sombra Negra (black shadow) death squads began targeting “homeboys” who were deported back to El Salvador. From 1998 to 2005, at least 46,000 such deportees found themselves marooned in Central America’s volatile barrios. As De Cesare notes, there are more than 4.5 million small firearms in Central America, the majority of them illegally owned. And 80 percent of homicides in Guatemala and El Salvador are carried out with such weapons. “What determines whether suffering is turned toward cruelty, or toward resistance and resilience?” she writes. As her photographs testify, such subtle distinctions erode during wartime.

Donna De Cesare won the Mother Jones International Photo Fund Award for Social Documentary in 1999. That same year, her photos accompanied a story about how tougher US immigration policy was forcing many refugees back to dangerous homelands. The images and caption information for this photoessay are from Unsettled/Desasosiego, recently published by University of Texas Press. For more information about De Cesare’s work in El Salvador, go to her website, Destiny’s Children.