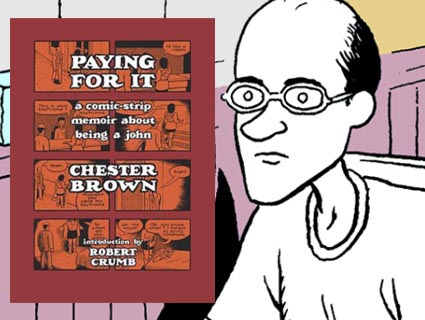

Back in 1981, the three Hernandez brothers, Gilberto, Jaime, and Mario, self-published their first issue of Love and Rockets, soon to become a groundbreaking comic book series. Almost three decades later, “Los Bros” are still going strong; Gilbert and Jaime in particular are still following some of the storylines they set in motion that very first issue. Their admirers are legion, with scores of fellow artists among them. In the introduction to last year’s The Art of Jaime Hernandez: The Secrets of Life and Death, written by comics historian Todd Hignite and published by Abrams ComicArts, graphic novelist and National Book Critics Circle Award finalist Alison Bechdel (Dykes to Watch Out For, Fun Home), writes “[I]t’s a good thing I didn’t discover Love and Rockets until I’d been drawing my own comics for a couple of years, or I’d still be a production assistant at the American Institute for Certified Public Accountants.” Click above to hear the audio version of this interview.

Mother Jones: For those who aren’t longtime fans, could you give us a thumbnail sketch of the almost 30-year relationship between the two women Maggie and Hopey from Love and Rockets?

Jaime Hernandez: Maggie and Hopey were two best friends who were introduced when they were around 15 years old. Hopey was a crazy punk rocker and Maggie was a Mexican girl from the barrio. They kind of fell in love in different ways, and just started to have adventures together. Sort of an urban Betty and Veronica.

MJ: Are there parts of your personality or your outlook on life that they might represent?

JH: Because Maggie’s my main character, a lot of my thoughts go into her; not all of my thoughts, but a lot of them. And they come from the lifestyle I was living at the time, as a young Mexican punk rocker.

MJ: What was your involvement with putting together The Art of Jaime Hernandez?

JH: I had the fun part, because all I had to do was answer questions! I got to talk about anything from my childhood, from how I draw comics to how I grew up reading comics. I didn’t have to write the thing.

MJ: In a past interview with Robin McConelly for Inkstuds.com, you said that Todd Hignite “really understood a lot of the personal things I was putting into my comics.” Can you elaborate?

JH: What I meant was that, when he asked me a question, I would just ramble like I am right now, and he seemed to get it. He could follow up on other questions that would help clarify what I was talking about; he just really seemed to understand a little kid growing up, liking comics, and then drawing them. It wasn’t from an academic point of view; it was more as if he understood that my love for all this came from when I was very young.

MJ: That comes through in the book, too; that it’s not academic and it’s not superficial. Was there anything you learned about yourself or about your work from going through this process?

JH: One thing I learned was that almost 30 years later, doing comics has become so personal to me that talking about me being five years old and talking about my comics is the same thing. So I’ll start talking about the comic and then I’ll talk about getting in trouble at school or something. It doesn’t always come out clearly in an interview, because I go from point A to point B and point C all the time. But I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s because all of it belongs together.

MJ: The book seems to be a pretty thorough study of your career. Is there anything you feel that Todd left out, or anything you wish he’d left out?

JH: Like the photo of me in my underwear? [Laughs.] Other than that, no. Of course I think, Whoa, they’re doing an art book about me and I’ve just started with my career! But you know, maybe once in a while I wake up in the middle of the night and think, Oh, I should’ve said that, or, Oh, I should’ve said this. But I think it’s covered pretty well.

MJ: On page 158—I think you’ll recognize what I’m talking about—Todd presents two drawings of people in cars; one done in 1983, and one in 1993, to illustrate your development to the point that, and these are his words, “contrasts are now defined by pure solids rather than shading hatch lines and an economical precision defines expressive body languages.” Why do you think your work developed this way?

JH: One answer I can give is that it just happened naturally; but another reason is that when I was young everything I drew contained so much detail; and as time went on I just started dropping all the lines I didn’t need. So the lines that were put down had to work really hard: One line had to do the job of 100 lines. It was a kind of natural progression.

MJ: Todd also asserts that when fan letters got fewer in the mid ’90s “both brothers felt an increasing sense of isolation due to the comparative lack of feedback,” and that this contributed to your decision to end the first volume of Love and Rockets and try new projects for a while. What effect does interaction from fans have on your work?

JH: Just that I know someone’s out there reading it. I like feedback. I don’t get the fan mail that some people think I do, but it’s a connection with a reader. I know there’s somebody out there that’s almost helping me do the work.

MJ: Gilberto once said in a response to a fan letter, “None of my characters has had a miserable depressing life; none.” In an indirect way I always felt that that statement got to the heart of all the work in Love and Rockets; would you agree?

JH: It’s hard to say, because I remember Gilbert answering that letter and I think he was in a bad mood; I think he didn’t like the letter writer or something.

MJ: He obviously was, but I took it to mean that he was saying that maybe there was a little condescension toward his characters, and he wanted to assert that, yeah, they’re going through these things, and it isn’t all sunshine and roses, but he didn’t think of them as pathetic. I wondered whether that has something to do with the times that you’re putting Maggie through whatever trauma she’s going through, that you’re still very conscious that that’s not all there is to her life.

JH: Sure, I know exactly what you mean. I like my characters, even the low ones. I think they belong. I think they have their place, even the unwanted ones, even the boring ones. Everyone’s got a life. I do like to concentrate on the lower class, so to speak; the second-, third-, fourth-class characters in life, because they’re more fun to do. Maybe because they have to work harder, they’ve got more to say. When I have a character that becomes successful, like a musician or something, I stop using him.

MJ: I always imagined that a lot of your strips are about people changing, and we all tend to change when something becomes uncomfortable for us.

JH: Right.

MJ: There’s a section about the commercial illustration assignments you’ve done. You describe how the little personal details that make your work don’t survive the editing process; how, “In any medium that deals with editing a lot of art is stripped down to this soulless thing.” Has there ever been a point for you where outside input in those commercial assignments was a source of inspiration?

JH: Hmmm. That’s hard to say. Let’s put it this way: There have been assignments where I was able to put in what I felt it needed and we came to an agreement. That doesn’t always happen; my brain works differently than yours. If you ask me to draw something for you, I’m gonna give you something you most likely didn’t expect. I’m taking it personally, seeing it from a whole different perspective. A lot of times that’s clashed with what they were expecting. And that’s when I ask: You hired me for what?

MJ: Jaime, thanks very much for talking with me. To have a book like this come out mid-career—you’ve got a lot to live up to, buddy!

JH: Exactly! Yeah, now I’ve gotta get to work, dammit!