Andy Katz/Zuma

Genetically modified foods remain controversial for many reasons, but at this point, the majority of scientists view them as safe to eat. The rest of Americans aren’t so sure: According to a major poll conducted in 2015, 57 percent of the general public thought consuming them was unsafe. Iowa State Professors Shawn Dorius and Carolyn Lawrence-Dill wanted to learn more about the root of this skepticism, so in 2017 they launched a research project to study American attitudes about GMOs.

During the initial phases of their research, Dorius remembers, something else was happening in the news: A steady stream of research and investigative journalism continued to draw attention to Russia’s influence on the United States’ presidential election. And that’s when the topic Dorius and Lawrence-Dill were studying collided with our country’s biggest political story: The same Russian media sites accused of stirring up controversy in the US election also seemed preoccupied with GMOs. So the team decided to add English-language Russian news outlets RT and Sputnik into their data gathering set.

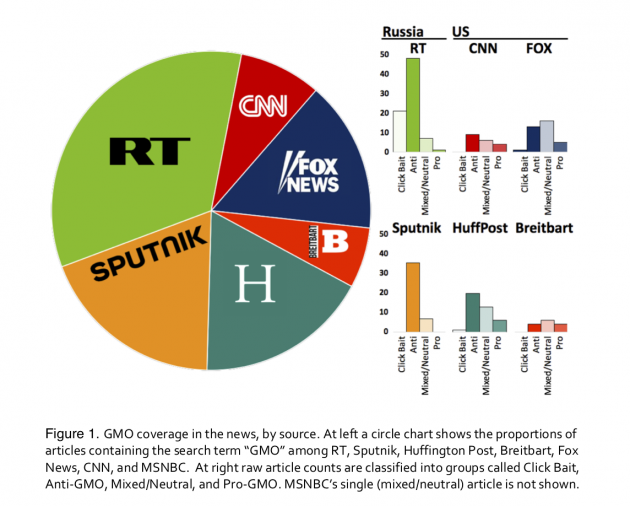

The researchers analyzed all news articles containing the word “GMO” published in 2016 by RT, Sputnik, Huffington Post, Fox News, CNN, Breitbart, and MSNBC. (They chose these publications based on Pew Research Center Report that categorized media according to political leanings and selected a small number of outlets intending to span the spectrum.) Crunching the numbers revealed that the Russian sites produced more articles about GMOs than the other five news organizations combined, according to the study—which is still under peer review and has not been published yet. An advance copy was shared with Mother Jones and other media outlets. (The Des Moines Register first covered Lawrence-Dill and Dorius’s findings after the duo presented at the Iowa State University Crop Bioengineering Center’s annual meeting.)

In contrast to US media coverage about GMOs, the paper notes, the Russian sites almost always portrayed them in a negative light. What also startled Dorius was that many of the Russian stories with “GMO” in the title had little to do with genetic engineering or agriculture at all. Rather, the term seemed injected into the story to connect it with negative emotions; the team dubbed these types of stories as “clickbait.” One example cited in the report started with an RT article entitled “Complex abortion debate emerges of Zika virus-infected fetuses.” At the bottom of the webpage, viewers were directed to “READ MORE: GMO mosquitos could be cause of Zika outbreak, critics say.” (That conspiracy theory, which hatched on Reddit, has since been debunked.)

Dorius cautions against putting too much stock in any one example because this was such a small study, looking at about 200 articles. Still, of all the controversial topics on the table, why GMOs? It certainly doesn’t fall in line with past Russian misinformation campaigns like Black Lives Matter or mass shootings. Maybe genetic engineering presents a new opportunity to promote Russia’s agricultural sector, which banned most GMOs in 2016. “Many American and European countries continue to produce and sell GMO products and the new law may further reduce the already scant presence of Western food in Russian stores,” the Moscow Times reported at the time of the decision.

In May of 2017, Senior Fellow for the American Council on Science and Health Alex Berezow posited that RT was pushing negative GMO stories simply to advance Putin’s agenda. “RT has never been fond of GMOs, which are largely the result of American innovation,” he wrote. “The anti-GMO stance is not based on science or health concerns; instead, it’s based entirely on hurting US agricultural companies.” (RT did not respond to a request for comment.)

There are at least 26 countries worldwide that ban GMOs. And in the US, the opposition has been rising in recent years. The National Science Foundation survey, a biannual assessment of American attitudes, found that the population who believe GMOs are “extremely or very dangerous” rose from 25 percent in 2010 to nearly 45 percent in 2016. Was a Russian “misinformation campaign” contributing to the uptick? “It is possible that messaging campaigns such as the one discussed in our paper are partly the cause, since the time ordering matches up,” Dorius says. “But at this point, that’s just conjecture.”