Sergey Bogdanov/Shutterstock

Cage-free eggs, once a niche product for ethically minded (and well-off) shoppers, are suddenly a hot commodity with an unlikely customer: Big Food. Sonic and Burger King are the latest to join a slate of companies promising to ditch eggs produced by caged hens.

They follow an unlikely trailblazer: McDonald’s, which announced in September that it would go cage-free by the end of 2025. That decision unleashed a “tidal wave of commitments,” says Paul Shapiro, vice president of farm animal protection at the Humane Society of the United States. The list now includes most major American fast-food chains, retailers including Target and Walmart, and food service providers, like Aramark and Sodexo.

Although the number of cage-free birds increased 37 percent last year, they remain less than 10 percent of the nation’s 277 million hens, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Now large egg producers are scrambling to catch up by investing in new cage-free facilities—a swift about-face for an industry that once vehemently fought efforts to eliminate the cramped, paper-sized “battery cages” in which the vast majority of hens spend their lives. In 2008, when California voted on Proposition 2, a measure that mandated that hens should be able to fully spread their wings “without touching the side of an enclosure or other egg-laying hens,” United Egg Producers, the industry’s primary trade group, spent $10 million in a failed effort to defeat the initiative. But this October, UEP President Chad Gregory told Politico that the group wouldn’t put up a fight in Massachusetts, where a measure modeled after California’s will be on the ballot in November.

Most companies, including McDonald’s, have given egg producers up to a decade to change how they house their hens. As Wired charts in detail, the industry is choosing to gradually phase out, rather than dismantle, a production system that’s been designed since the 1950s to provide maximum efficiency. Today, Americans demand 6 billion to 7 billion eggs each month, and they expect every dozen to come relatively cheap.

That means that while cage-free is often portrayed as a nostalgic return to pre-mechanized farming, the newest egg facilities are not like your grandfather’s bucolic little chicken farm. At nonorganic farms, where outdoor access isn’t required, large egg producers are primarily building multitiered aviaries—stacked arrangements in which thousands, if not tens of thousands of birds roam throughout the barn, hopping from level to level. “There are birds by your feet, your knees, your shoulders—cities of birds,” explains Shapiro.

Giving hens the simple ability to move around prevents many of the worst health problems associated with battery cages, Shapiro says, by strengthening brittle bones and allowing them to act on their natural instincts to roost and forage.

But in these large, industrial aviaries, the birds “don’t typically go outside,” says Shapiro. And letting a flock of birds roam within a closed, confined aviary presents its own concerns. A three-year study produced by a consortium of egg providers, academics, and advocacy groups found that aviaries had nearly twice the death rate of caged systems. Most of the difference had to do with aggression between the birds and outbreaks of cannibalism.

Cannibalism is a learned behavior, a nasty symptom of industrial breeding and housing, says Joy Mench, an animal behavior specialist at the University of California-Davis who co-led the study. Outbreaks are more likely to flare up in densely stocked aviaries, where hens are given unfettered access to other birds. And for that reason, aviary managers continue to rely on the standard industry practice to lessen the risks of pecking: cutting off the sharp tips of the hens’ beaks.

Reduced air quality in the closed barns is another concern for both birds and workers, who need to spend more time managing the hens in a cage-free system. In battery cage systems, birds were separated from their waste. Without that separation, ammonia buildup can occur when feces aren’t removed in a timely fashion, particularly in cold climates. But the most acute problem is that a moving flock clogs the air with dust. “There were days when you could hardly stand to walk into that aviary,” says Mench, referring to the Midwestern egg facility where the study was conducted. “You couldn’t see 4 feet in front of your face.”

Additionally, in both caged and uncaged systems, disease spreads like wildfire. Last year’s avian flu outbreak, which killed millions of hens and sent egg prices skyrocketing, is thought to have originated in backyard flocks but took its heaviest toll as it blazed through crowded industrial barns.

“People are going to love that they are cage-free, but you have to look at the whole system,” says Janice Swanson, a professor at Michigan State University and a co-author of the study. “It’s going to be a lot of work before cage-free is environmentally sustainable and actually does what we want it to do for the hens.”

The study suggested that bigger, so-called “enriched” cages, with room for the multiple birds to move and exhibit more natural behaviors, may be a better bet for health and safety than aviaries. Those systems are legal under California law, which didn’t ban cages but instead mandated minimum space requirements. But since they don’t meet the corporate cage-free pledges, egg producers don’t have an incentive to build them.

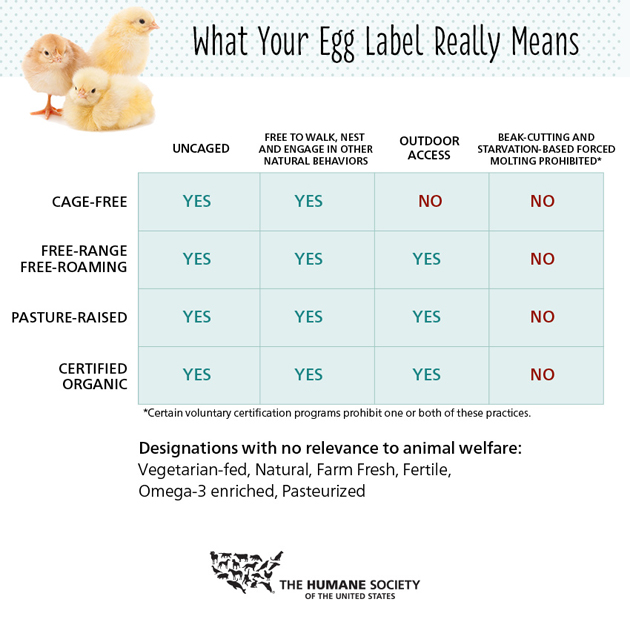

So while cage-free systems remove many of the inherent cruelties of battery cages, the welfare of the hens inside them hinges on how these facilities, which can range from packed industrial aviaries to smaller farms with ample space and outdoor access, are designed and managed. That can be difficult to decipher from the labels on an egg carton.

If you’re looking to further mitigate the cruelty behind your next omelet, the Humane Society recommends looking past labels like “vegetarian-fed,” “natural,” or “farm fresh,” which are stamped on cartons for marketing purposes. Pasture-raised, certified organic, or free-range are typically better bets for eggs produced by a happier, healthier hen—if you can stomach the higher cost.