John Nowak/CNN via Zuma

Has Sen. Cory Booker (N.J.) been reading Mother Jones? Because the point he made, during the second round of presidential debates debate on Wednesday night about the significance of the Paris climate accord probably sounded familiar to anyone who has followed our attempts to contextualize the much-lauded agreement. “Nobody should get applause for rejoining the Paris climate accords,” he said. “That is kindergarten.”

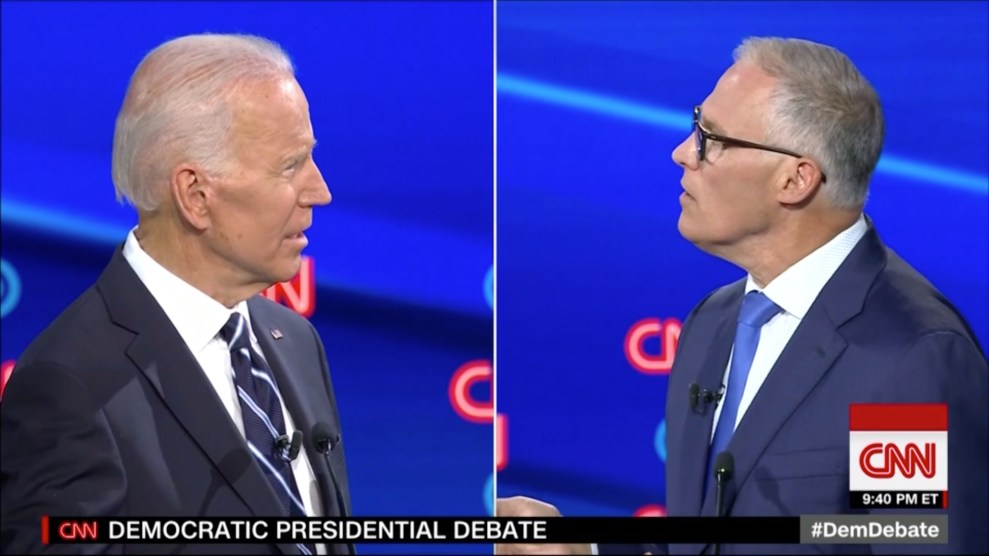

Booker joined Washington Gov. Jay Inslee to pile on the criticism directed at former Vice President Joe Biden’s climate plan. An adviser described Biden’s climate strategy as “middle ground” before the campaign released a plan that was met with relatively positive reviews from environmentalists in June. “Middle ground approaches are not enough,” Inslee said sharply. “There is no middle ground about my plan,” Biden replied, underscoring his seriousness in addressing climate change by pointing to his role in the 2015 global Paris climate agreement and promising to convene leaders again to “raise the standard.”

Ever since President Donald Trump announced his intention to withdraw the United States from the agreement in 2020, the Paris accord has been wrongly considered the gold standard for climate change action. For Democrats, the reality is everyone is ready to rejoin on day one of their administrations. Almost the entire rest of the world has agreed to adopt the voluntary terms of the accord that pressured, but did not require, countries to reduce their pollution and urged the historic polluters in the industrialized world to do more to help. Trump has inaccurately described it as a disproportionate burden for the US. While the Democrats’ mischaracterizations aren’t nearly as bad, re-signing Paris is, like Booker says, “kindergarten,” because even as ambitious as the Paris agreement was, those voluntary pledges fall short of what is needed to prevent runaway warming.

As I wrote last fall when former California Gov. Jerry Brown convened a climate summit in San Francisco that was meant to show Trump—and the rest of the world—that he didn’t doom the Paris agreement:

The timing of the San Francisco summit is also significant, occurring during the midpoint between the Paris meeting and the next major deadline in 2020. That’s when the 200 participating countries not only have to ensure they are on track to meet the modest pledges they made in Paris, but that they are exceeding them, because targets established in the Paris pact don’t approach the level of emissions cuts necessary to keep global warming below a destructive 2 degrees Celsius. If all the pledges were added together and adhered to, the global goal would still not be achieved.

Together, the global commitments that roughly 7,000 cities and 6,000 companies have made since Paris do pack a punch. The entities making pledges on clean energy, forests, oceans, and infrastructure represent $36 trillion, far larger than the US economy. In the US, actions by the subnational sector helped the country meet nearly half the commitment it made in Paris. An analysis this summer from economic think tank the Rhodium Group found that existing policies in the US mean we are headed toward a reduction ranging from 12 to 20 percent of emissions by 2025, still falling short of its stated 26-28 percent goal. That still leaves some room for uncertainty, given the capacity of forests to absorb carbon and energy costs and the unclear future of many federal climate policies.

But distinguishing yourself in a competitive primary on rejoining the agreement—which is as easy to do as a signature—is not an impressive or forward-looking position to take. And yet, many of the candidates don’t seem to understand that: “I would take any Democrat on this stage over the current president of the United States, who is rolling it back to our collective peril,” Harris said. “I would re-enter us in the Paris agreement.” Kirsten Gillibrand (N.Y.) echoed, “And I will not only sign the Paris global climate accords, but I will lead a worldwide conversation about the urgency of this crisis.” Of course Biden and all of his competitors have promised to do more, and to hit effectively zero emissions by 2050 or sooner. Simply saying you will sign the accord once more is basic stuff—so basic, that it means virtually nothing on its own.

The fundamental problem is that US domestic emissions, and the commitments the US made under the Paris agreement, were still too weak to hit international targets for containing global warming. But the candidates have also had a tendency to campaign on an equally outmoded policy of restoring the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan targeting coal in the power sector. I’ve explained how the economy has blown right past those too-conservative targets already:

With hindsight, it’s clear that the Clean Power Plan was not ambitious enough. Even without going into effect, carbon pollution from the power sector has come down down 28 percent from 2005 levels, which isn’t so far off, and is well ahead of schedule, of the plan’s goal of cutting pollution 32 percent by 2030. In the last nine years, 290 coal plants have shuttered or set retirement dates, and about 50 have done so since Trump took office. Coal has simply been unable to compete with cheaper natural gas and renewables. “The power sector has been moving away from coal. There’s huge increase in renewables and a big increase in the deployment of energy efficiency,” says David Doniger, climate and clean energy director at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “All those things have led the carbon-sector power emissions down.”

The NRDC says the pace of progress suggests that any new, updated Clean Power Plan should look past the Obama administration’s vision and set a more ambitious goal of cutting nearly twice as much pollution—60 percent by 2030. The NRDC says such a reduction would, because of advances in technology, cost less than the original rule was estimated to while saving more than 5,000 lives by reducing illness related to burning coal in 2030 alone.

There are plenty of plans, including Biden’s, that go beyond reinstating outmoded Obama-era policy. But for most of the candidates, the focus on it in the debates seems to sidestep the basic fact that there’s so much more they should be doing. For example, Cory Booker could lead by example by finally releasing his own climate change plan.