Nasir Kachroo/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press

This story was originally published by The HuffPost and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A thick smog settled over New Delhi as winter began in India last year, forcing medical professionals to declare a public health emergency. Residents swarmed local hospitals complaining of respiratory problems. Cricket players were forced to put on anti-pollution masks during a national match between India and Sri Lanka. And United Airlines canceled flights into the city, citing the air-quality concerns.

Air pollution isn’t among the causes of death that medical examiners list on death certificates, but the health conditions linked to air pollution exposure, such as lung cancer and emphysema, are often fatal. Air pollution was responsible for 6.1 million deaths and accounted for nearly 12 percent of the global death toll in 2016, the last year for which data was available, according the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

“Air pollution is one of the great killers of our age,” Philip Landrigan of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai wrote in an article published in the medical journal The Lancet.

India’s late environment minister, Anil Madhav Dave, made headlines last year for denying there was proof that air pollution was singularly responsible for death in India. Dave conceded that air pollution “could be one of the triggering factors for respiratory associated ailments and diseases,” but he blamed the negative health effects on other issues: poor diet, occupational hazards, socioeconomic status and genetics.

Dave died in May 2017 from cardiac arrest. The new environment minister, Harsh Vardhan, has also said that “to attribute any death to a cause like pollution, that may be too much.”

But there are numerous studies linking air pollution to morbidity around world.

“There is a huge amount of data linking outdoor and indoor air pollution with adverse health effects, including acute and chronic disease, exacerbations of chronic disease and death,” said Dr. Barry Levy, adjunct professor of public health at Tufts University School of Medicine.

Of the 6.1 million air pollution death in 2016, 4.1 million are attributable to outdoor, or ambient, air pollution, according to IHME. Such pollution comes from sources like vehicles, coal-fired power plants and steel mills. Household, or indoor, air pollution is a more pressing problem in low-income countries due to the use of indoor fires for cooking and heat, and it’s linked to an estimated 2.6 million deaths per year. (In India at least, the total air pollution death rate has declined since 1990 even as the outdoor death rate went up in recent years—due largely to a decrease in the number of deaths attributable to indoor air pollution. Scientists don’t completely understand how ambient and household air pollution deaths interact, and there’s some overlap between them, which is why the sum of ambient and household air pollution deaths exceeds total air pollution deaths.)

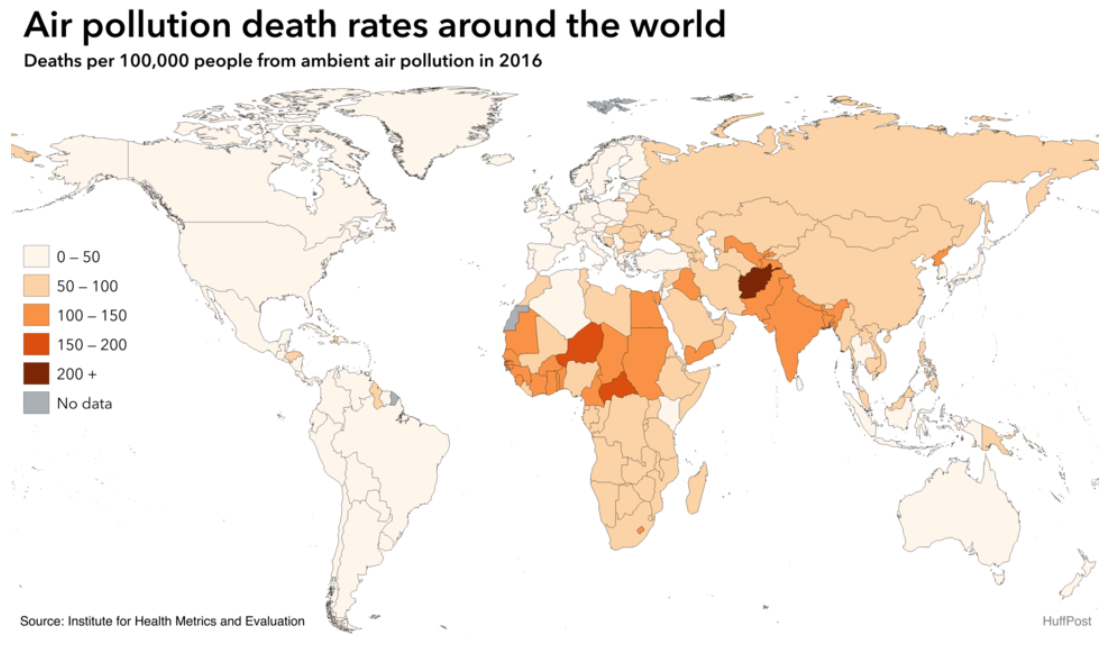

Developing countries bear the brunt of the world’s pollution problem

Air pollution is undoubtedly a global public health problem, but not all countries are equally affected.

As many as 1.6 million deaths were attributable to air pollution in India in 2016, according to IHME. That same year, all air pollution was linked to almost 123 out of every 100,000 deaths in the country—among the highest in the world.

“When it comes to the number of deaths from air pollution, India is No. 1,” Landrigan told HuffPost.

Afghanistan and several African countries have higher ambient air pollution death rates than India, likely because of the extremely dusty conditions in those countries, combined with other pollution sources, like vehicle emissions and crop burning.

“With globalization, mining and manufacturing shifted to poorer countries, where environmental regulations and enforcement can be lax,” Karti Sandilya, one of the authors on the Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health, told Reuters. “People in poorer countries—like construction workers in New Delhi—are more exposed to air pollution and less able to protect themselves from exposure, as they walk, bike or ride the bus to workplaces that may also be polluted.”

Delhi has become a gas chamber. Every year this happens during this part of year. We have to find a soln to crop burning in adjoining states

— Arvind Kejriwal (@ArvindKejriwal) November 7, 2017

North India’s topography makes its pollution problem worse, Vox noted in November. The region acts as a basin, trapping pollution from crop burning outside the city and mixing it with industrial pollution from within city limits. And that mix of pollution sources is most intense during the coldest months of the year.

In fact, the problem is getting so bad that some people are moving out of New Delhi altogether. Television personality Mayur Sharma is perhaps the most notable example: He left his job and moved his family out of the capital to escape the pollution.

“The right to breathe is, you would think, the most fundamental right—more than food, more than water. And that right is being seriously compromised right now,” Sharma told NPR.

As India’s economy has expanded, the country has struggled to keep up with the environmental costs of that growth. Premature deaths from air pollution have stabilized in China, which rivals India in terms of pollution problems and population. That stabilization occurred partly because China has used fines and criminal charges to crack down on pollution. India’s government, however, seems more focused on economic growth than on protecting air quality and the environment.

Air pollution—and climate change—link the global community in deadly ways

Because air pollution and related health problems can travel, no country can solve its air pollution problem alone.

Air pollution from Chinese consumption was linked to an estimated 3,100 premature deaths in the U.S and Western Europe in 2007, according to an article published last year in the journal Nature. At the same time, nearly 110,000 premature deaths in China were linked to pollution prompted by consumption in the U.S. and Western European.

“Air pollution can travel long distances and cause health impacts in downwind regions,” Qiang Zhang, co-author of the article and a researcher at Tsinghua University in Beijing, explained to Popular Science.

Climate change will likely exacerbate those global concerns, according to public health experts.

They anticipate that climate change will trigger a host of public health problems, including heat- and cold-related deaths, increased disease risk and mental health problems from climate displacement and extreme weather conditions.

Climate change also contributes to air pollution trends—hotter temperatures increase wildfire risk, and wildfires create ambient air pollution. It also increases ground-level ozone, which is a main ingredient in urban smog, and can trigger health problems like chest pain, throat irritation and lung inflammation, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

“Higher temperatures are expected to increase the rate of ozone formation,” Levy said.

This makes it even more crucial for local, national and intergovernmental organizations to join forces to address air pollution.

As Kirk Smith, a professor of global environmental health at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health, put it, “Air pollution doesn’t care about political boundaries.”