The collapsed facade of an apartment building in Lower Manhattan, New York, after Hurricane Sandy.Daniel Schnettler/ZUMA

This story first appeared on the Atlantic Cities website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In the face of threats natural or man-made, history has shown that our first impulse is often to diffuse the population. The 1956 Highway Defense Act, for instance, was enacted to achieve two goals: first, to spread Americans out from concentrated inner cities in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack; and second, to create a network of highways with bridges elevated enough to transport American intercontinental ballistic missiles. Today, as we confront climate-related risk, population diffusion may be a knee-jerk response, but it is important to remember that this sprawl only exacerbates the problem. Policies that support the development of dense urban areas are critical tools in mitigating climate-related risks.

In the long run, we already know that urban dwellers consume less energy per capita than their suburban and exurban counterparts, which makes the case for the importance of density in tackling climate-related risks. But even in the shorter term, cities allow us to be more resilient. In the aftermath of Sandy, higher-density neighborhoods with centralized infrastructure such as underground power and mass transit generally fared better and recovered more quickly than lower-density areas. It is particularly telling that in the aftermath of Sandy, higher-density neighborhoods—from downtown Brooklyn and Battery Park City up to Harlem—were up and running within a week. By contrast, lower density areas like Staten Island and Breezy Point—with their single-family homes, elevated power lines, timber construction, and auto-dependency—took longer to recover. Dense conditions come with a greater number of redundancies, a fundamental characteristic of resiliency. Most residents of high-density areas don’t rely on a single hospital or one grocery store. Instead, they have a network of them, allowing one or a few to malfunction without creating a system failure.

Regardless of the inherent environmental advantages of urban living, however, cities are vulnerable sets of materials and systems, and Sandy revealed some of their glaring deficiencies. In some dense public housing communities, residents went weeks without power and resources due to outdated building systems. But poor residents housed in New York’s privately-built mixed-income rental housing developments fared far better. Our task as a society confronting climate-related risks is to make tactical improvements in these areas of deficiency without seeing it as a failure of dense urban environments across the board.

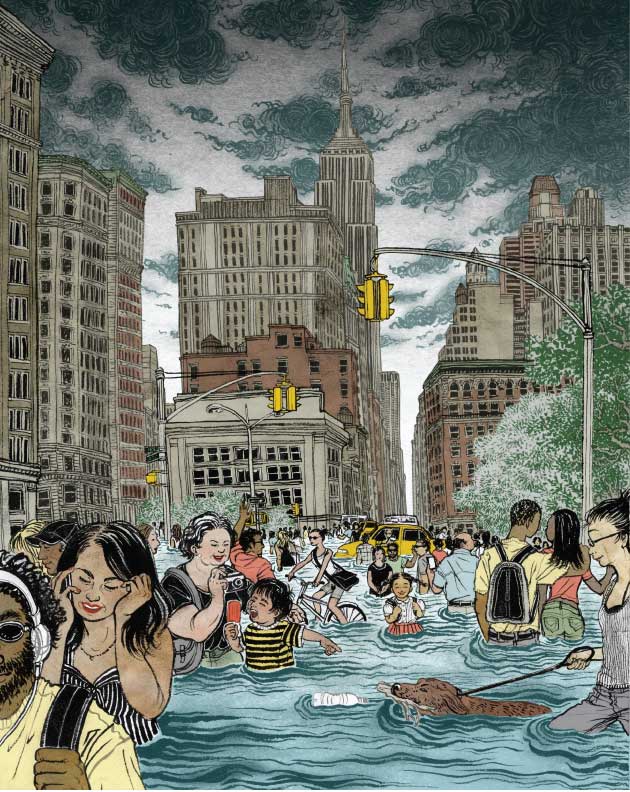

We must continue to develop our cities—even in those areas that lie in potential flood zones. There are 300,000 New Yorkers living in our most vulnerable flood zones, with even more development being planned in those very zones. While this reality has been subject to criticism, we should no more abandon those plans than we should retreat from Lower Manhattan, Red Hook, or DUMBO. We must find “both-and” solutions that allow high-density, mixed-income, transit-oriented waterfront development able to withstand climate-related risks. If we abandon waterfront areas, for example, we risk further limiting supplies of housing, which will make the city unaffordable to an increasing number of people. Our recent research at Columbia University’s Center for Urban Real Estate indicates that in order to house a million new New Yorkers by 2040, we will have to provide much more dense, mixed-income housing along the post-industrial waterfront because it continues to offer the only available, transit-oriented, economically viable land. Again, critics will assert that to put more New Yorkers in harm’s way is madness, but when coupled with well-conceived land-use plans that incorporate regional resilience considerations, these areas can become integral in providing these newcomers with a more affordable place to live within the city (rather than dispatching them to a gas-guzzling life in the suburbs).

For many waterfront cities, dramatic interventions ranging from man-made wetlands to sea gates may very well be necessary to cope with storm surges and rising sea levels. But at the same time, we must rethink the wisdom of oceanfront single-family homes on barrier beaches. These sandbars are meant to protect the mainland, but this is only effective if their dunes have not been destroyed by housing construction. This irresponsible development is made possible by private insurance policies that are backed by the federal government—a form of subsidy for low-density areas that, like the mortgage-interest deduction and federal highway funding, we could redirect for mixed-income urban housing designed with appropriate resilience measures.

Climate change is definitively upon us, and protection from its most adverse effects must be a top priority, especially in concentrated population centers and coastal cities. From natural disasters to terrorist attacks, cities, at first glance, may appear to be outsized objects of vulnerability. But when one examines the history of urbanization, as Larry Vale and Tom Campanella do in their book The Resilient City, cities have proven remarkably durable in the face of disasters both natural and man-made, from Chicago and San Francisco at the start of the twentieth century to Nagasaki today.

Unlike the blatant shortcomings of sprawl, the resilience of cities is often under-appreciated. New York after September 11 and several California cities that were struck by earthquakes or fires in the latter half of the twentieth century are prominent examples of American cities that, with the right mix of private and public-sector coordination, have grown stronger and more sustainable than before. In time, and with the right mix of pro-growth policies, dense American cities can withstand the effects climate change, and even more important, they can address those causes—surging energy use and irresponsible land-use patterns—that make climate change such an insidious threat.