Photo: Mary Anne Andrei

This series was originally published online by OnEarth magazine. Follow continuing coverage of the story at OnEarth.org.

John Bolenbaugh paced the courtroom in Battle Creek, Michigan, Tuesday morning waiting for his attorney to arrive. Tom Warnicke was set to file a motion to dismiss his client’s lawsuit against former employer SET Environmental—part of a settlement agreement Bolenbaugh’s legal team reached with opposing counsel Douglas Van Essen on Sunday. But for now, it was just Bolenbaugh and SET president David de Vries in the courtroom, together in awkward silence.

“You know you still got supervisors telling workers to cover up oil,” Bolenbaugh said. “There’s another whistleblower that came forward last week.” This second whistleblower, a current SET employee, was to have been Bolenbaugh’s surprise witness—and he couldn’t resist telling de Vries.

But according to Bolenbaugh, SET’s president—who had sat attentively through two days of tense trial testimony—didn’t want to talk. “Let’s not do this right now,” he pleaded.

“Okay,” Bolenbaugh persisted. “I just thought you should know.”

After months of fervent avowals that he would never settle with SET—and heated allegations that the company had engaged in a willful coverup at the behest of Enbridge, Inc., the Canadian energy behemoth whose pipeline spilled more than a million gallons of heavy crude into western Michigan waterways on July 25, 2010—Bolenbaugh’s mild-mannered agreement to an out-of-court settlement offer was a serious anti-climax. And not just because it robbed the public of a juicy conclusion or the spectacle of Bolenbaugh in the witness box. After so much buildup, the settlement came with no findings of guilt.

Van Essen told a reporter for the Kalamazoo Gazette that there are no conditions requiring SET to admit to any of Bolenbaugh’s allegations of an oil coverup—or to concede that his firing was the result of going to the EPA and other governmental bodies. “We’re looking at it from an economic perspective,” Van Essen said. Bolenbaugh, for his part, stipulated that he was unwilling to agree to a gag order, but he did agree to keep financial terms of the settlement undisclosed. And with that, the suit was settled—and all the major issues it raised left unresolved. The news came as a shock to many who had been following the run-up to the trial, but this had been in the works since court let out last Thursday.

On that evening last week, after Bolenbaugh’s stunning (even for him) courtroom gaffe—in which he petulantly complained to the bailiff that the court video cameras were not turned on, raising the ire of Judge James C. Kingsley—I caught up with his legal team at J. W. Barleycorn’s, a cookie-cutter hotel bar, all formica surfaces and oak panels, under the Kellogg Conference Center where they were staying. The sullen-faced Steve Hnat, Warnicke’s trial consultant, agreed to let me listen in on two conditions: 1. I couldn’t write about anything they said until after the trial was over; and 2. I had to join them in drowning their sorrows—and, judging by the graveyard of tumblers before them, they were already several Jamesons ahead of me. With Judge Kingsley so obviously irritated by their client and his unruly behavior, Warnicke and Hnat had to figure out what to do next.

The simplest path would be to stay the course, to hope that Bolenbaugh’s testimony, scheduled for the next day, would be compelling enough to the jury that it would outweigh bench rulings against him. But that was also the risky route. Earlier that day, SET’s HR Manager Jill Schoeneman had insisted that Bolenbaugh was not fired for going to the EPA and blowing the whistle on a coverup but rather for violating SET’s company policy by talking to the press—and then bragging about it to SET’s client, Enbridge. “He was fired for insubordination,” Schoeneman had said. “We can’t have an insubordinate employee on our site.” With SET hanging its defense on a claim that he was insubordinate, Bolenbaugh had to give off the appearance of being obedient and respectful. The last thing he could afford to do was create an impression among the jury that he was a defiant publicity hound puffed up with self-importance.

Hnat stood in for Bolenbaugh as they role-played his testimony, working through the points he needed to be sure to hit. He had tried to report illegal behavior to his superiors, but they had failed to act. He had gone to the EPA, but they too had sat idle. Going to the news media and directly to Dave Murphy, the Enbridge supervisor, was a moment of desperation after weeks of fruitless efforts to follow protocol. “We all know,” Hnat said, gesturing toward me, “that the news media has the power to bring pressure on the government.” Most importantly, Bolenbaugh had gone to this desperate length out of a selfless concern for his community, a fear that toxic material—recklessly spilled by a foreign company and shabbily cleaned up by out-of-staters—was being concealed at unknown risk to his family and neighbors.

As they rehearsed, Warnicke paused over the part of the discussion that focused on Dave Murphy. On the witness stand, Schoeneman had painted a scene of Bolenbaugh approaching Murphy at lunch, at a picnic table with co-workers assembled. Bolenbaugh, in her telling, was wearing his SET hard hat when he delivered the threat that he was going to the news media, and it was the public embarrassment of that moment—and his official representation of SET—that had led Murphy to call and insist that he never be allowed back on the jobsite. But Bolenbaugh had told Warnicke that the conversation took place after normal work hours at the next day’s jobsite while he and Murphy awaited the arrival of the rest of the team; it had been done in private, quietly. Schoeneman wasn’t there and had only Murphy’s word to go by—but if this confrontation had indeed taken place in front of a crowd, why didn’t SET produce other witnesses? Was Dave Murphy complaining to SET about insubordination or alerting them that an Enbridge-ordered coverup was about to be exposed?

Warnicke was still working over the discrepancies when Bolenbaugh arrived to prep. As he practiced giving his testimony, Bolenbaugh’s mood swung wildly—one minute giving a heartfelt accounting of the inner turmoil he had felt as he reached the decision to approach the EPA and the news media, the next minute turning self-aggrandizing and rhetorical as he dissected the day’s testimony against him, disappearing into the weeds of irrelevant details gotten wrong by witnesses. Hnat sat patiently, encouraging the right tone when Bolenbaugh found it, cautioning him to stay on topic when he veered.

This is Hnat’s bread and butter—and why he’s been a valued asset at Fieger Law for so long. But even he confided to me that Bolenbaugh was among the most unpredictable clients he had ever encountered. “He frightens me more as a witness than Kevorkian did,” he said. Hnat had worked as a trial consultant on several cases handling “Dr. Death” Jack Kevorkian when Fieger Law was defending him for participating in assisted suicides. “With Jack, he could be in the court room but ignoring everything going on around him. He taught himself Japanese during one trial. John’s not like that; he can’t let a single detail go by without an argument.” We talked about Warnicke’s opening statement, when Bolenbaugh had briefly interrupted—interrupted his own attorney’s opening statement on his behalf—to correct a detail. Bolenbaugh had laughed about it afterward as evidence of his strict allegiance to the truth, but Hnat worried that he was coming off not as truth-driven but rather as cocky, obsessive, and (at least to the two small business owners in the jury box) the kind of employee you dread.

Warnicke had retreated into near silence by the time Hnat rose from the table and proposed a game of pool. He got change from the bartender and stacked the quarters high for the coin-op table, and he kept the rounds of drinks coming. Bolenbaugh, a pool-shark, was so much better than everyone else that he offered to play one-handed, and soon a small crowd gathered to watch him drop strings of long shots without seeming to line them up at all; sometimes he wouldn’t even bother to bend over, firing from the hip. No sooner had a group of young guys at the bar asked him how he’d learned to shoot this way than Bolenbaugh was giving his life story, then opening up his laptop to show them some of his videos on YouTube. Meanwhile, the time between shots grew and grew as Warnicke and Hnat huddled, leaning close enough to avoid being overheard. It seemed clear that Bolenbaugh’s outbursts in court, his erratic run-through of his testimony, and now his grand-standing—even in a hotel bar, the night before his testimony—were combining to produce more than general worry from his legal team. They were plotting a new course.

* * *

The next morning, last Friday, I was on my way into the courthouse when Douglas Van Essen, walking with SET’s president David DeVries, intercepted me at the entrance.

“You know we’re not going, right?” he asked.

I was too confused to come up with anything more than: “No.”

“Tom slipped in the hotel shower. He’s in the hospital.”

Warnicke had injured his calf while playing tennis a couple of weeks before; when he slipped in the shower that morning he had further torn the muscle, leaving him hobbled and unable to make the court date. When I finally got a hold of Bolenbaugh on his cell phone, he was at his attorney’s bedside.

“How’s Tom feeling?” I asked.

“I’m in a lot of pain,” I could hear a groggy Warnicke say over the phone. Despite the delay in his chance to take the stand, Bolenbaugh seemed unusually buoyant, giddy even.

I called Hnat, who was already on his way back to the Fieger offices in Southfield, Michigan.

“He’s not going to take the stand,” Hnat said. “We’re going to settle.”

But this was anything but a defeat, Hnat explained. The night before, as Warnicke listened quietly to the discussion of Dave Murphy’s conversation with Bolenbaugh and Murphy’s subsequent phone call to Jill Schoeneman, he saw a way to climb the ladder—a way to leapfrog SET and take the fight directly to Enbridge. Bolenbaugh could settle with SET—which would be scored as a victory in the press and would yield more than enough money to sustain Bolenbaugh for a few years. In the meantime, they would sue Enbridge for tortious interference with employment. By calling for Bolenbaugh’s firing—an act undertaken by SET within hours and for stated reasons that SET’s own HR manager now admitted were pretexts—Enbridge had disrupted the bond between employer and employee. Now all Warnicke had to do was convince Bolenbaugh to take the deal. And that’s where Hnat came in.

“I told him I wanted him to serve the papers himself,” Hnat told me. “I said, ‘I want you to take a camera crew with you. I want to see it all.'”

“You knew which buttons to push, didn’t you?” I asked.

Hnat laughed. “I like to think I’m good at what I do.”

When I spoke to Bolenbaugh later about the plan, he acknowledged Hnat’s ploy—but insisted that he didn’t feel the least bit manipulated. He said only, “That would be great video, wouldn’t it?”

But it almost didn’t come to pass. Tuesday morning, early, I started getting a string of texts from Bolenbaugh.

“I went out to celebrate with my friends and i couldn’t smile,” the first began. “I am still up at 5am and i can’t sleep. I feel sick to my stomach for giving authority to my attorney to except [sic] a settlement that i NEVER imagined SET would offer.” He understood that this would be notched as a win, but “I didn’t do this for a win or for any amount of Money,” he insisted. But now, the paperwork had been entered with the court. “im [sic] told that i can’t turn back,” another text read. “That the judge will force the settlement no matter what complaints i have. What have I done? Letting this corruption go unpunished in the legal and public eye because I’m scared that the Judge wont give me a fair trial after asking if the cameras will be on to document history.” The last message was concluded with a frowny-face emoticon.

By now, it was hard to tell: was Bolenbaugh actually feeling remorse for accepting a settlement from SET. Or was he trying to have it both ways: part of a strategy—engineered by Warnicke—to take a deal but allow Bolenbaugh to object to the arrangement in court, when it was too late to withdraw it and too late for the judge to do anything other than order the plaintiff to be quiet. Or had Warnicke completely lost control of his client?

More texts came soon after.

“The only positive feelings i have is the fact that i have No gage [sic] orders,” he wrote. “The question I have for myself is did i sell out or was this settlement a way to go after the largest tar sand pipeline company in the world by using my settlement to fund a nationwide attack on Enbridge with better camera equipment, unlimited gas, banners, signs and town hall speeches that will be so many I will lose count.”

Bolenbaugh seemed to be settling into the narrative now. His texts began focusing on getting his watchdog group—HELPPA.org—off the ground, educating the nation about the dangers of tar sands. “I will be there at the next tar sand spill evacuating residents and watching every move and clean up procedure Enbridge, Trans canada, Exxon, BP and any others make,” he wrote.

An hour later, he sent another text: “I just told tom im not taking settlement. And to be ready tuesday morning.”

* * *

By the time Bolenbaugh reached Tom Warnicke, his attorney had already spoken to Judge Kingsley’s clerk on a joint conference call with Van Essen. When Warnicke called Van Essen back to say that his client was getting cold feet, Van Essen sent a written motion to the judge, asking for enforcement of the settlement, even if Bolenbaugh opposed it in session. “A party’s ‘change of heart’ is not grounds to set aside a settlement agreement,” Van Essen wrote, according to the motion obtained by the Battle Creek Enquirer. Some time Tuesday, Warnicke finalized the agreement, signing on Bolenbaugh’s behalf—and the deal was done.

All day on Monday, Bolenbaugh kicked around the idea of making a statement in court—rising to tell the judge that he’d only given his okay because he believed it would be impossible to receive a fair trial in his courtroom. But, when the time came, Bolenbaugh signed his name without incident (adding only a note that he would not agree to any gag order, other than the “exact amount” of his payment); then, the settlement was read into the record, and the jury was released.

Bolenbaugh told me that Warnicke asked him in the elevator not to tip off reporters about the upcoming action against Enbridge. But Bolenbaugh was worried that Warnicke might try to back out if the promise wasn’t made public—so he told me all about the plan on the phone (and asked me to make sure it appeared in my story), he told the local reporters in person before they left the courthouse, and I’m sure he’ll have a video with that promise posted to his YouTube channel by the end of the week. For all of Bolenbaugh’s suspicion, however, when I reached Steve Hnat by phone in Southfield, there was no flicker of hesitation. He was clearly preparing for Warnicke to file suit against Enbridge—”They’re the real bad guys,” Hnat said—and he expected to be counseling Bolenbaugh through the process. More than that, he regarded Bolenbaugh’s acceptance of the deal as more than a legal victory.

“Maybe it’ll be an epiphany for John,” Hnat said. “Maybe he can move beyond the immediacy and the emotion of the situation and begin to recognize that—you know what?—this could really make a difference for a lot of different communities. Not for him but for those communities.” Hnat is a trained psychologist who had a practice for years before becoming a trial consultant—and for just a moment, he sounded more like Bolenbaugh’s therapist than part of his legal team. Every trial is partly about resolving the psychodrama of the principal players, he explained. “If he can sublimate that part of his emotional need and force it to be secondary,” Hnat said, “then maybe he can effect real change.”

* * *

Perhaps this is a victory for Bolenbaugh. And, if he goes to Enbridge’s office in Marshall to deliver the papers for a lawsuit later this week—let’s just be honest—it will be great video. But a part of me understands Bolenbaugh’s reluctance to declare victory. SET hasn’t admitted to anything, and a trial against Enbridge pushes judgment about the quality and sincerity of the company’s cleanup effort in Michigan to the end of 2013. In the meantime, Bolenbaugh has enough money to fund his ongoing campaign against Enbridge, but the company also staves off—for now—national negative PR and the possibility of additional suits. That is also another 18 months for the spill to recede into memory, both in the popular imagination and in the minds of any potential jury pool.

Further postponing the lawsuit of John Bolenbaugh leaves the focus, for now, on the relatively limited issue of his termination. A local report in the Battle Creek Enquirer, for example, ran under the headline “BOLENBAUGH FIRED FOR INSUBORDINATION“—but glossed over the fact that several SET employees agreed that Jason Buford, a supervisor at O’Brien’s Management charged with helping Enbridge meet its EPA deadlines, issued direct orders to cover up oil. The larger issue than whether Bolenbaugh was fired properly or improperly resides in two simple facts: Bolenbaugh’s former co-workers confirmed under oath that Enbridge’s management contractor instructed crews to ignore pockets of oil in September 2010, and today—more than 18 months later—oil remains in the spots where those instructions were given.

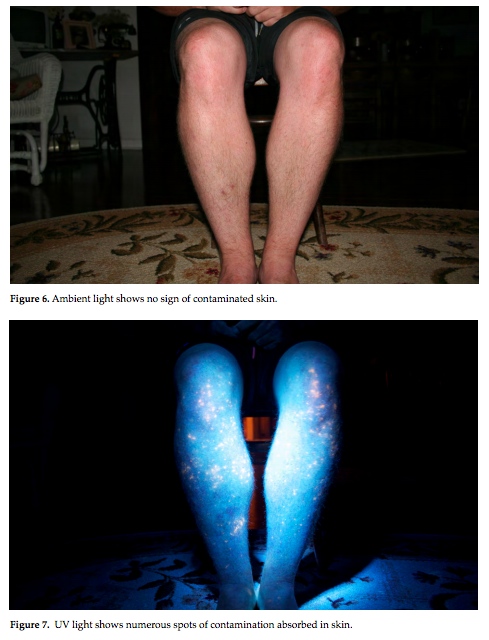

Meanwhile, the EPA has reopened a three-mile stretch of the Kalamazoo River and intends to reopen the remaining 37 miles by June. And yet, even as the river is again available for recreation in the summer months, residents have been cautioned not to put out kayaks or canoes except in approved areas, not to eat any of the fish they catch, and have been told to expect to see submerged oil bubbling to the surface when they swim; wash stations with wipes have been set up at sites approved for swimmers. Thus, the essential questions—bigger even than whether the 6B pipeline ruptured due to Enbridge’s negligence, or whether the company’s contractors sought to cover up oil, bigger even than the nagging questions about the health effects for area residents—are whether we, as a country, are willing to accept this level of risk to our waterways and, if so, whether we find this level of cleanup adequate. Do we consider a river with inedible fish to be restored? Do we find a riverbed slimed with submerged oil to be the same river it was before a spill?

In the end, the dispute between the EPA’s documents certifying large areas of the Kalamazoo River as clean and Bolenbaugh’s view of the cleanup as failed boil down to this: the EPA does not equate a 100 percent completed cleanup with a river that is 100 percent clean. The Kalamazoo River may never be the same again, explained Ralph Dollhopf, the EPA’s federal on-scene coordinator and incident commander. Getting the river totally clean by invasive measures might create a disruption to the environment more damaging than leaving small amounts of tar sands crude and its chemical diluents behind. But are these really our only two options? Are we left to choose between one form of environmental destruction and another?

Maybe it is time, instead, to insist on greater oversight of the nationwide complex that carries a highly toxic crude through old and outdated pipes at great risk of rupture and potentially irreversible consequences to the environment and to public health. If those risks can’t be minimized, if those consequences can’t be mitigated, maybe it is time to halt the flow of tar sands oil altogether.