Illustration: Christoph Hitz

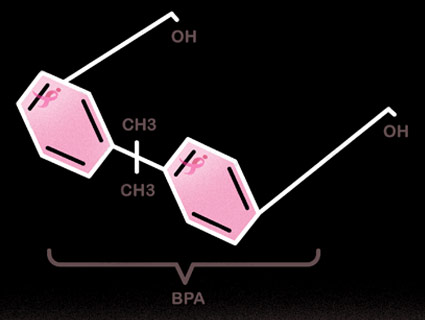

If you’ve ever bought something pink to support breast cancer research, there’s a good chance a portion of the money went to Susan G. Komen for the Cure, the largest nonprofit in the world solely dedicated to eradicating the disease. Famous for its fundraising races and pink gear, the foundation has been fighting breast cancer for three decades. So it may come as a surprise that Komen has posted statements on its website that dismiss links between the common chemical bisphenol A (BPA) and breast cancer, even while funding research that explores that possible connection.

BPA is found in all manner of consumer goods, from plastic water jugs to receipts to the liners of food cans. Critics have pointed out that Komen receives generous donations from private industries who use those same chemicals in their products, and who also downplay health concerns. Is that what’s driving Komen’s position on BPA? “Absolutely not,” said Katrina McGhee, Komen’s executive vice president and chief marketing officer. In multiple interviews with Mother Jones, Komen executives were adamant that their sponsors have no effect on any of their policy decisions.

“I want to be very clear,” said Komen President Elizabeth Thompson. “We are not influenced at all by any subpart of any one of our funders.”

And yet, it’s hard to ignore mounting scientific evidence that strongly suggests a link between BPA and cancer. The United States’ President’s Cancer Panel concluded in 2010 that “more than 130 studies have linked BPA to breast cancer, obesity, and other health problems.” A number of studies have found that the chemical causes breast cancer in lab animals. In human cell cultures, BPA has caused breast cancer cells to proliferate and has also reduced the effectiveness of chemotherapy. In September, a study by the California Pacific Medical Center found that BPA even made healthy breast cells behave like cancer cells and decreased the effectiveness of yet another breast cancer drug. Frighteningly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that BPA is in the urine of more than 90 percent of the United States population. Researchers believe this figure reflects continuous exposure to the chemical.

In April 2010 Komen posted an online statement saying that BPA had been “deemed safe.” And a more recent statement on Komen’s website about BPA, from February 2011, begins, “Links between plastics and cancer are often reported by the media and in email hoaxes.” Komen acknowledges in its older statement that the Food and Drug Administration is doing more studies on BPA, but also says that there is currently “no evidence to suggest a link between BPA and risk of breast cancer.”

Just one of many pink-packaged products whose sales support Susan G. Komen for the Cure. Cambodia4kidsorg/Flickr“I think that’s at best, misleading, and at worst, demonstrating really significant ignorance by whoever at the Komen Foundation wrote that,” said University of Missouri biology professor and BPA expert Dr. Frederick vom Saal in a telephone interview, reacting to Komen’s 2011 BPA statement. “When you think of this as a foundation that’s out there supposedly protecting women from factors that are involved in breast cancer, I find that statement to be just astounding.”

Just one of many pink-packaged products whose sales support Susan G. Komen for the Cure. Cambodia4kidsorg/Flickr“I think that’s at best, misleading, and at worst, demonstrating really significant ignorance by whoever at the Komen Foundation wrote that,” said University of Missouri biology professor and BPA expert Dr. Frederick vom Saal in a telephone interview, reacting to Komen’s 2011 BPA statement. “When you think of this as a foundation that’s out there supposedly protecting women from factors that are involved in breast cancer, I find that statement to be just astounding.”

Komen’s chief scientific adviser, Dr. Eric Winer, dismissed the criticisms as inflammatory. “If a woman is particularly worried about plastics, she can avoid plastics in her life,” he told me.

That’s not as easy as it sounds, since the chemical is found in so many products. The list of Komen sponsors that use BPA include the Coca-Cola Bottling Company (which says BPA is safe, but that it is nonetheless looking for alternatives for its canned soda) and General Mills, which still uses the chemical in most canned foods but did recently introduce BPA-free organic tomato cans. Another sponsor is Georgia-Pacific, a subsidiary of famously anti-regulation Koch Industries and major manufacturer of epoxy resins that contain BPA.

Another manufacturing company, 3M, maker of of Scotch Tape, has donated more than $1 million since 2007 and is a member of the American Chemistry Council, a powerful trade group that argues that BPA is safe. Komen also has a partnership with DS Waters, which delivers the type of water bottle cooler that you’re likely to find in an office setting, The bottles get a pink cap for the Komen partnership, but Komen doesn’t mention that those pink-topped bottles are made from polycarbonate plastic that contains BPA.

Reacting to Komen’s April 2010 statement on BPA, Dr. Megan Schwarzman, a family physician and research scientist at the University of California-Berkeley School of Public Health, noted in a telephone interview that “the people who produce chemicals often cite language like that to justify business as usual.”

And indeed the American Chemistry Council did use that statement to justify business as usual, with a post on its Facebook page reading, “Leading breast cancer org Susan G. Komen says no evidence to suggest a link between BPA & risk of breast cancer.”

In an in-person interview, Komen president Thompson agreed that there are still many unanswered questions about environmental toxins and breast cancer. Komen’s chief scientific adviser, Winer, joining in the interview by phone, said that because of those unanswered questions, Komen executives do not yet want to make “definitive” statements about chemicals on the website. In response, I asked: “You don’t want to make a definitive statement, then why do you say that BPA, in that one statement [from April 2010], has been deemed safe?”

“I can only say that we’ve spent hours,” Thompson said. “Hours and hours and hours looking at the wording.”

Throughout the interview, Winer deflected other experts’ criticisms by stressing personal responsibility. “Nothing stops an individual woman from living her life a certain way. And if she chooses to do that, she can do that.”

Komen’s downplaying of the link between chemicals and cancer isn’t limited to BPA; the foundation also lists exposure to organochlorine pesticides, a category that includes the infamous DDT, as one of six “Factors That Do Not Increase Risk.” But like BPA, many pesticides have estrogen-like traits. A 2007 study published in Environmental Health Perspectives even suggested that women exposed to DDT as adolescents were five times more likely to develop breast cancer during adulthood.

Komen’s position on chemicals’ role in cancer reflects a larger debate within the public-health community over the importance of addressing the influence of environmental factors on cancer. Only about 10 percent of cases of breast cancer in the United States can be traced to hereditary factors, research shows. “We now know from just a whole lot of science that environmental variables have a strong influence on gene expression,” said Dr. Ted Schettler, Science Director of the Science and Environmental Health Network.

Yet scientists, including the President’s Cancer Panel report released in 2010, say that research on the environment and cancer as a whole remains grossly underfunded. “There traditionally has been tremendous resistance to looking at environmental issues. And that’s because there are very powerful interest groups lobbying against doing that,” vom Saal said.

Ranked in the 2010 Harris Interactive Polls as the second most trusted nonprofit in America, Komen awarded researchers $55 million worth of grants in 2011. Critics accuse major cancer organizations of pouring every dollar into drug studies, but in Komen’s case, that’s actually not true. In the 2011 research portfolio, a small portion of Komen’s funding is going toward specific environmental exposures—including a $450,000 study on BPA by a Komen-funded researcher who hypothesizes that BPA “causes or accelerates breast cancer.”

Winer said that before 2011, Komen also decided to fund an approximately $1.25 million panel at the Institute of Medicine on environmental exposures, precisely because of such intense debate around the issue. The results will be announced in December, he said. “If the Institute of Medicine comes forward and concludes that there are statements on the website, or statements that any of us have made that are not accurate, we’re going to correct those.”

In 2007, Komen funded another review of studies on environmental toxins and breast cancer through the Silent Spring Institute. This made Komen’s online statements all the more disturbing to the institute’s executive director, Dr. Julia Brody. She says that she wrote to Winer twice about her concerns. “I felt a particular obligation to bring these issues to Komen’s attention because the information on the website conflicts in various ways with the findings of the science review that we conducted with Komen funding,” Brody told me via email.

For its part, Komen maintains that its close ties with industry are critical to its success. Indeed, the foundation’s diverse group of sponsors has helped it invest close to $2 billion in its mission. The money funds projects like national research and free biopsies for uninsured women. “For anyone to suggest that the reason that the environment isn’t studied is because, somehow, doctors are interacting with pharmaceutical companies over drugs, is truly an inaccurate statement,” Winer said. “And bordering in my mind as a very offensive statement.”

Searches of Winer’s published research show that he has received grant money from pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca and Genentech in the past. In an interview, he said he’s also served as an unpaid and paid consultant to various pharmaceutical companies.

“I’m less involved from a financial standpoint than almost anyone I know,” Winer said. In addition to his work at Komen, Winer is the Director of the Breast Oncology Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and a Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical Center. “I actually, for many years, accepted no personal honoraria from any pharmaceutical company. And this is a time, when in fact, what we desperately need are for people in academia and people in industry to work closely together. Because people in industry, or the companies, are the ones that have the drugs.”

In any case, some have argued that debates over specific cases of industry influence miss the larger point: that it’s the government’s job to protect consumers through better regulation of chemicals. But because of gaps in the Toxic Substances Control Act, the EPA has toxicity data on less than 1 percent of the 83,000 chemicals in commerce, according to a widely cited paper published in Environmental Health Perspectives. And the US Food and Drug Administration can’t seem to make up its mind on the subject. The agency said that BPA is safe in a draft report in 2008. But the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel then broke the news that the FDA had based its draft report on industry-funded studies. (The FDA has since said it has some concern over health risks of BPA.) Even such mainstream groups as the American Nurses Association are lobbying to reform the United States’ chemical regulation policy. But until that policy reform actually happens, it’s up to consumers to research potentially unsafe, everyday products themselves.

On September 19, after the troubling results from the California Pacific Medical Center study on BPA were announced, Komen’s website shows that it updated its “Factors That Do Not Increase Risk” page. But for the pesticide and plastics statements, not a word was changed.