Photographs by Matt Slaby

TO GLIMPSE THE FUTURE of the Great Plains, you take Route 191 past the Crazy Mountains through Lewistown, Montana, to a 123,000-acre tract of former ranchland where human habitation is scant and the bison roam. The soil contains bentonite, a kind of clay used in makeup. The land gets a measly 11 inches of rain per year, rendering it unfit for most agricultural uses. When it rains in the spring, which isn’t often, the mud dries into hard ruts that last into the fall and jolt the spine of even the most deliberate driver.

I pull over to the side of the road and watch a red-tailed hawk hunting overhead. A pronghorn deer startles at my approach and nervously circles the spot where it dropped its newborns. The prairie undulates like a vast inland sea, with no cars or houses visible for miles in any direction. In the spring, the grasslands are dotted with purple, yellow, and white flowers, and waterfowl rise from the marshes and watering holes. By August, temperatures can hit 107 degrees and up. In the winter, the prairie roads are covered in six-foot drifts of snow in which animals and people freeze to death.

What makes this landscape so remarkable is the intimation of what some people see as the future of conservation in America, a future that many people who live here—who see themselves as the true conservationists—don’t want. It is a big, dreamy idea that began in academic journals and is now slowly making its way into county land registers. One day, if all goes according to plan, the surrounding ranches and public lands will be part of a 3 million-acre grassland reserve run by the American Prairie Foundation (APF), a private entity formed at the urging of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and bankrolled by big-name donors (PDF) who believe that landscapes like this one should be objects of awestruck contemplation, rather than pastures for cattle.

The notion that people living on the Plains should cede their land to bison is rooted in a deliberately heretical 1987 article in the academic magazine Planning, titled “The Great Plains: From Dust to Dust.” Authored by professors Frank and Deborah Popper (he teaches at Princeton and Rutgers; she teaches at Princeton and the City University of New York), it suggested that a large portion of the Great Plains—comprising most of Montana, the Dakotas, Wyoming, and parts of six other Western and Midwestern states—would become almost completely depopulated within a single generation, and should therefore be “returned to its original pre-white state,” i.e., a bison range.

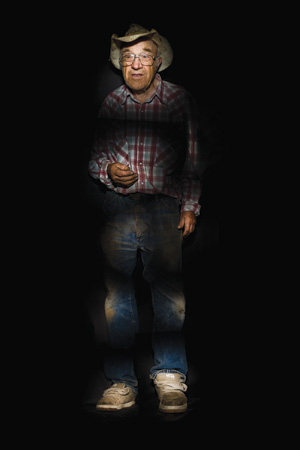

Gene Barnard, 92, has a 23,000 acre ranch within the proposed buffalo reserve and doesn’t plan to sell it.The Poppers’ proposal, which they called the “buffalo commons,” struck many residents of the states in question as the very apogee of East Coast academic insanity, and few readers imagined that it would become a foundation of public policy in the West. Yet the couple’s predictions are proving prescient. According to a 2009 Census report (PDF), nearly two-thirds of Great Plains counties declined in population between 1950 and 2007, with 69 of those counties losing more than half their people. As the people are leaving, the buffalo are multiplying. Major herds in Montana include the 3,900-head Yellowstone herd, the 6,000-head herd at Ted Turner’s ranch on the Gallatin River, and the 400-head National Bison Range Herd near Flathead Lake, established by Congress at the turn of the 20th century to save the American bison from extinction.

Gene Barnard, 92, has a 23,000 acre ranch within the proposed buffalo reserve and doesn’t plan to sell it.The Poppers’ proposal, which they called the “buffalo commons,” struck many residents of the states in question as the very apogee of East Coast academic insanity, and few readers imagined that it would become a foundation of public policy in the West. Yet the couple’s predictions are proving prescient. According to a 2009 Census report (PDF), nearly two-thirds of Great Plains counties declined in population between 1950 and 2007, with 69 of those counties losing more than half their people. As the people are leaving, the buffalo are multiplying. Major herds in Montana include the 3,900-head Yellowstone herd, the 6,000-head herd at Ted Turner’s ranch on the Gallatin River, and the 400-head National Bison Range Herd near Flathead Lake, established by Congress at the turn of the 20th century to save the American bison from extinction.

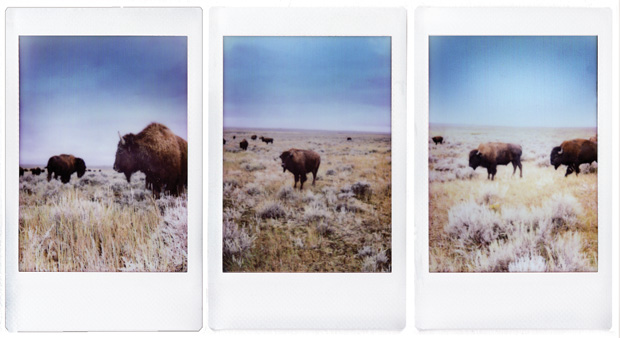

Yet all of these efforts pale next to the APF’s plan to create a reserve the size of Connecticut in this stretch of Montana—an expansive savannah that looks like parts of Africa and is capable of supporting many thousands of bison. The core of this proposed range is an area twice the size of Seattle where the APF’s starter herd now resides. The foundation’s strategy is to buy up local ranches in order to gain control over associated grazing leases on vast expanses of public land, with the goal of returning a wide area of Montana to something resembling its pre-European state at an estimated cost of $450 million. (The group has raised $40 million so far.) With sufficient land to roam and grass to eat, a bison herd will naturally double every four or five years. The estimated number of bison required to maintain sufficient genetic diversity within a herd is around 400, and the APF is already more than halfway there. In January 2010, it received 96 new bison from Canada, descendants of the Pablo-Allard herd, one of the last significant free-ranging bison populations in the United States.

“This land is cheap, it’s for sale, and it’s intact prairie,” says Alison Fox, the APF staffer who brought me here. The county’s population is roughly 40 percent (PDF) of its 1919 peak (PDF). The average rancher, Fox tells me, is 58 years old, and most people home-school their children because the schools are too few and far between. The people who make their lives in this environment are a special breed of individualists, but there are fewer and fewer of them, she says. That is why the bison are coming back.

BRYCE CHRISTENSEN is a huge, gentle, bald-headed man with a walrus mustache who spent more than three decades working for Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, which was pretty much the dream job of every boy in Montana whose family didn’t own a profitable ranch. Now he spends his days managing the APF reserve, checking on the animals, and removing fences and other relics of human habitation from the plains. “We got about 14,000 acres of pasture open to the bison now,” he says, gesturing out at the range. “They’d like bigger, I think.” While Christensen has removed about 15 miles of fence thus far, the herd is capable of traveling well beyond the current pasture boundary in a single day of grazing, which means that there is always more fencing to be taken down.

Bison are a keystone of an ecosystem that once included more than 1,500 species of plants, 350 birds, 220 butterflies, and 90 mammals. Mountain plovers use bison wallows as nesting sites. Bison keep trees from invading the open grasslands by scoring them with their horns, and they disperse seeds by eating and excreting them. When the bison die, they are eaten in turn by bald eagles, ravens, and black-billed magpies.

A ride across the prairie in Christensen’s mud-caked Dodge truck reveals that this landscape is not as untouched as it looks. Every mile or so, we pass a man-made watering hole for cattle, which will eventually dry up or get choked out by invasive species. (See “Predator vs. Alien.”) One of the dominant plants here is crested wheatgrass, a hardy Russian perennial that the US government introduced to the Plains in the 1930s for use as forage. “It’s very challenging to get rid of crested,” Christensen admits. The pretty yellow flowers are sweet clover, another imported species. “We’re gonna do a series of 300- to 500-acre burns starting out by those trees,” he explains. “After it burns, it will be low enough that the bison will eat it when the shoots come up.”

For all the effort required to restore the grasslands, perhaps the most challenging part of Christensen’s job in this ecosystem is to establish friendly working relationships with the local ranchers, whose way of life the APF ever-so-gently aims to eliminate. “Many of them want to stay,” he says when I ask him how the ranchers feel about selling their land. “If that changes, we would like to be seen as the buyer of choice.”

The Phillips County News had been particularly vociferous in its opposition to the project. Christensen mentions a series of cartoons that depicted the APF as skylarking weirdos whose idea of progress was to take the country back to the 1850s. “Circle up the wagons, folks,” editorialized a staff writer assigned to the story. “We’re about to be overrun by a bunch of eastern based nature lovers herding buffalo onto our range.” Christensen feels that the paper has let local passions get in the way of the facts. “I think the source of the fear,” he says, “is that we are very open about our dreams of what this landscape will look like 25 years from now.”

We climb a rise, and I encounter about 70 bison, old and young, disporting themselves on the beginnings of the reserve. A circle of huge bulls sits in the dirt, occasionally lifting their massive heads to survey the scene. The older bulls are distinguished by heavy beards and full bonnets. By comparison, the younger bulls look more like skinny hipsters from Williamsburg. A playful red calf, four to six weeks old, trails behind its mother, who is visiting with two other cows. Female calves remain with their mothers for up to three summers, while males leave earlier. “I think that’s No. 5,” Christensen says, pointing to a large cow that has a reputation for charging visitors.

Dragonflies flit through the tall grass as the air around them vibrates with the deep, resonant rumble of bison talking to each other about the weather, or whatever it is that they talk about. I notice that one of the calves has an injured leg and is trying to interest its mother in feeding it. “Would you help that animal?” I ask Christensen. “No,” he answers shortly. “We did have a mother die in childbirth,” he adds, after a pause. “Hey, that’s nature.” In the wildlife service, he might have shot a calf in the same predicament. “If you do shoot it,” he says, “it’s definitely going to die.”

After half an hour of persistent effort, the limping calf convinces its mother that it’s not about to die, and she decides to let it nurse, swishing her tail with what seems like mild annoyance for the first 30 seconds or so as the hungry calf suckles. Perhaps encouraged by the unexpected strength of the response, she stands patiently as the calf feeds. “These bison have just done phenomenal,” Christensen says with evident satisfaction. “It’s just great country.”

WE WALK FOR A WHILE, our conversation punctuated by the crunch of dry grass underfoot and the gentle brushing of thistle, sage, and meadow foxtail (PDF)—yet another invasive species that will be hard to eradicate. The new bison from Canada are doing fine, Christensen says. I will be able to identify them by the letters “CAN” branded into their flesh, a condition imposed by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to help prevent the spread of disease from bison to cattle.

While technically classified (PDF) as livestock, bison are loathed by local ranchers, who worry that the animals might infect their cattle with anything from anthrax and mad cow disease to the dreaded bovine brucellosis, an infectious disease that causes cows to spontaneously abort their calves. The ranchers’ antipathy stems from a fear of damage to their herds, and also from what the bison have come to represent—namely, the desire of conservationists to destroy their way of life in the pursuit of a whimsical dream of returning to an imagined Eden.

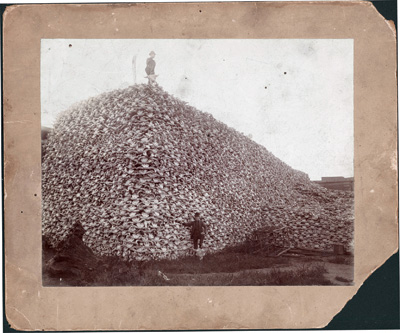

Bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer, circa 1870. Burton Historical Collection/Detroit Public LibraryThe local Native American tribes, especially the Gros Ventre on the nearby Fort Belknap reservation, support the APF but are also wary about embracing the idea of a vast bison reserve with too much enthusiasm. Those living on the reservation are sometimes employed by the ranchers, whose very recent ancestors exterminated the bison in an astonishingly short period of time thanks to the Sharps buffalo rifle, a weapon that could take down a bull (or a warrior on horseback) at a distance of 1,500 yards. In 1881, when the Northern Pacific railroad reached Miles City, Montana, the seat of Custer County, a commercial buffalo hunter named Vic Smith killed 4,500 bison in less than a year, getting three dollars apiece for their hides. If money was the primary motive for buffalo hunting, the destruction of the economic and cultural life of the Plains tribes to make way for white settlement was a close second. By 1886, there were hardly any bison left in Montana.

Bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer, circa 1870. Burton Historical Collection/Detroit Public LibraryThe local Native American tribes, especially the Gros Ventre on the nearby Fort Belknap reservation, support the APF but are also wary about embracing the idea of a vast bison reserve with too much enthusiasm. Those living on the reservation are sometimes employed by the ranchers, whose very recent ancestors exterminated the bison in an astonishingly short period of time thanks to the Sharps buffalo rifle, a weapon that could take down a bull (or a warrior on horseback) at a distance of 1,500 yards. In 1881, when the Northern Pacific railroad reached Miles City, Montana, the seat of Custer County, a commercial buffalo hunter named Vic Smith killed 4,500 bison in less than a year, getting three dollars apiece for their hides. If money was the primary motive for buffalo hunting, the destruction of the economic and cultural life of the Plains tribes to make way for white settlement was a close second. By 1886, there were hardly any bison left in Montana.

We get back into Christensen’s truck and drive over to the Fort Peck Reservoir, formed by one of largest earthen dams in the world, a massive public project that displaced many of the ranchers here from their original landholdings on the Missouri River. As we sit on a high bluff looking down on the empty lake, Christensen ponders the future of the dream to which he has dedicated himself. The land will return to its natural, untouched state. Families might come and camp here and see what Lewis and Clark saw. We drive over to a ring of empty canvas yurts erected by the APF to host visitors. Among the recent guests was a group of Chinese conservation workers who slept out on the prairie and photographed bison with their new cameras.

A bank of hard gray clouds looms above the hills. I decide to watch the coming storm from inside the APF ranch house, which is furnished in comfortable Western style. I gaze out the living-room window at the high clouds shadowing low-slung power lines and a single gray metal Quonset hut. A tracing of a public map is laid out on a table by my side, next to a list of local ranchers and their landholdings. The map shows where each of their properties is located in relation to the reserve. It is an unsettling document, a roll call of families whose neighbors have long since given up on this inhospitable landscape: Kevin Cass, Gene Barnard, Bill French, and the Barthelness family, including Leo, Chris, Darla, and Leo Jr. Above my head is a handmade charm that contains a legend darkly etched in glass, which reads, “There’s nothing like a dream to create a future.”

MY READING for the evening is a journal article by a World Wildlife Fund staffer named Steve Forrest that lays out the innovative strategy on which the APF’s approach to conservation is founded, and which brought the APF to Phillips County, where it has purchased 12 ranches to date. Whoever controls the ranches also controls the much larger tracts of grazing land that the ranchers lease from the Bureau of Land Management. Because these leases are tied to the ranch rather than the rancher, and because bison are the legal equivalent of cattle in the eyes of the USDA, each acre of ranchland the APF buys and stocks with bison turns into three acres of freshly minted nature park. Connect the private ranches and their leased BLM grazing lands with existing national parks and tribal lands, and a 3 million-acre grassland park is born.

Phillips County was chosen for this experiment because BLM lands comprise one-third of its land base, amounting to 1 million acres in a county with fewer than 4,000 residents (PDF). There are about 500 farms and ranch operations in the county, a manageable number given that these operations run a combined $1.7 million in the red, making it a buyer’s market.

At the WWF offices in Bozeman before my trip, Steve Forrest told me that bison were, in fact, a late addition to the grand vision of a grasslands reserve. The idea of using the animals to anchor the park emerged from a 2006 meeting of about 50 conservationists and biologists at Ted Turner’s ranch in New Mexico. Attendees produced a map of projected bison recovery on the Plains over the next 20, 50, and 100 years and issued what has become known as the Vermejo Statement, which reads (PDF) in part:

“Over the next century, the ecological recovery of the North American bison will occur when multiple large herds move freely across extensive landscapes within all major habitats of their historic range, interacting in ecologically significant ways with the fullest possible set of other native species, and inspiring, sustaining and connecting human cultures.”

The statement’s origins, Forrest said, lay in the convergence of the WWF’s work on grasslands with the work of the biologist Jim Derr at Texas A&M University. Forrest nods and smiles when I mention the Poppers, but he is quick to claim that they had little to do with the practical side of building a large-scale conservation project on the prairie—a fact that, while true, is also a way of eliding the politically damaging connection to a couple whose names have become a byword for the notion that humans are less important than bison. Derr concluded (PDF) that many of the wild bison in conservation herds lacked sufficient genetic purity to pass on the pristine bison genome. The introgression of cattle genes into bison herds can be the product of the deliberate cross-breeding of bison and cattle for commercial purposes, or it can happen naturally. Either way, many wild bison in the fabled conservation herds were, by the standards of the purists, hardly bison at all.

At Turner’s ranch, Derr presented his findings (PDF) to an audience that Forrest describes as “anyone who had any bison weight at all.” The meeting, held in a gorgeous Spanish-style lodge once owned by the Pennzoil Company, was hosted by the Turner Foundation. “Ted was suddenly very interested, because one of the herds tested that did not have cattle DNA was his herd,” Forrest explains. “The message was that we could lose wild bison. It was critical.” Turner himself attended some of the sessions along with his head rancher Marv Jensen. After the sessions, the attendees dined on bison steak and plotted out a practical path to making their dream a reality.

The population of Phillips County peaked in 1919. It has since declined by nearly 60 percent.As the largest mammal native to North America, bison are “charismatic megafauna” capable of attracting human backing for conservation in a way that, say, prairie dogs can’t. The bison’s physical charisma, its place in the American historical imagination, and its role in the prairie ecosystem—not to mention its legal status as a type of cow—made it the perfect anchor for the grassland park the WWF hoped to establish.

The population of Phillips County peaked in 1919. It has since declined by nearly 60 percent.As the largest mammal native to North America, bison are “charismatic megafauna” capable of attracting human backing for conservation in a way that, say, prairie dogs can’t. The bison’s physical charisma, its place in the American historical imagination, and its role in the prairie ecosystem—not to mention its legal status as a type of cow—made it the perfect anchor for the grassland park the WWF hoped to establish.

Forrest sees the landscapes he seeks to preserve as being very much like great works of art. “It’s not like we are creating this for some alien race to appreciate later,” he told me, drumming his fingers on a wooden conference table. “We take out a few fences, we knock out a few power poles, and that’s it: That’s what the first humans saw when they stood on a tall peak looking down at the valley. That is a really compelling, spiritually important thing that we need.” Through such visions, Forrest says, human beings can be brought to appreciate their connectedness to other organisms and to a larger ecosystem—a conservationist’s version of the emotions that animate our romantic attachments to art and religion.

The fact that Forrest’s plan pushes this aesthetic of harmonious interconnectedness by means of old-fashioned legal and political leverage and donations from wealthy benefactors has not been lost on some residents of Phillips County. For ranchers, the creation of a buffalo commons is not an act of restorative devotion but the forced transformation of the farms and ranchlands to which they and their families have devoted decades of toil.

The APF’s cause was not helped by the appearance of a Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks manager named Arnie Dood at the annual meeting of the Phillips County Livestock Association last June. According to the Phillips County News, Dood told the ranchers they could “either be a part of setting what the future is going to look like” or they could sit around and complain; he added that “people are xenophobic in Central Montana.” (Dood denies making the comment. “What does that word mean?” he asks, laughing.) The paper also ran a cartoon depicting a city slicker seated on the rear end of a sleeping bison, heading toward the year 1850; he holds a pamphlet bearing the initials “WWF,” “APF,” and “PETA.” In editorials, articles, and letters, the News and its readers gleefully attacked the APF from every angle—fears that the buffalo would infect people’s cattle with brucellosis, elitism of reserve proponents, the return of wolves to the prairie. (See story below.) In one of many angry letters to the editor, retired wildlife biologist Jack D. Jones railed against the influence of “global organizations like the WWF” and warned that “this could be shoved down our throats, like ‘Obamacare.'”

The paper covered one meeting where more than 200 county residents aired their fears. Among them was Rose Stoneberg, a local activist and landowner who warned that the APF would try to get the land through monument designation rather than paying landowners. Maxine Korman, another local, was paraphrased by the paper explaining that the grasslands plan was only a small part of “an apparent United Nations project designed at creating a wildlands refuge extending from the Yucatan to the Yukon.” At another public meeting, the News noted, someone proposed a vote on the idea of allowing free-roaming bison onto the Plains. The tally was 92 against, zero in favor.

GENE BARNARD, a fit 92-year-old rancher whose spread is part of the proposed reserve, lives next door to the APF base camp in a group of houses inhabited by family members, dogs, trucks, and old machinery. He knows as much about Phillips County as anyone alive. Since he was born here in 1918, the county’s population (PDF) has declined (PDF) by almost 60 percent.

When I get out of my truck inside Barnard’s family compound, I am surrounded by a pack of five barking dogs who hold me at bay until the rancher’s son-in-law, Jerry Mahan, arrives to rescue me. A tall man with long sideburns and sun-frazzled hair, he wears a frayed army jacket, sunglasses, and jeans, all seeming better suited to a crisp fall day than to the current 98-degree heat. In addition to giving him a certain resemblance to the late Hunter S. Thompson, the layers protect him from the swarms of dive-bombing mosquitoes that breed in the gullies after it rains. When I suggest that driving on the badly rutted dirt roads must be especially difficult during the brief wet season, he nods. “Three feet of gumbo and 800 feet of sand,” he says, jerking his thumb towards the road, and then nodding towards the open prairie beyond. “We’ve taken three people out in body bags. This country isn’t forgiving.”

He walks me to the door of the small clapboard house where Gene Barnard is awaiting my visit at a kitchen table piled high with newspapers and ketchup bottles. He rises to greet me, then bends down to chase a pair of yapping dogs with a plastic fly swatter. He apologizes and offers me a seat. His parents came to Montana before the First World War, he says, lured by the promise of bountiful land. “The Great Northern Railway, they put out advertisements everywhere. Grain this high,” he chuckles, holding up his hand to the level of his chest. “It didn’t take too long to find out, coming out here from places with 20 to 30 inches of rain, that 10 inches was the short end of the stick.”

Barnard’s father, two uncles, and a brother-in-law migrated from Virginia to North Dakota to Montana, and his father took a job as a teacher before filing a claim on some upland pasture. When I ask why his father claimed such undesirable land, he tells me that he had the same question. “I asked him, ‘My God, when there’s all this lowland, why’d you file on upland?'” Barnard remembers. “He said the sheep was eating it off, it was all green then.”

The family ranch eventually grew to 23,000 acres, but life was always hard. As a boy, Barnard remembers being sent out to pick beans and gooseberries and to weed the garden before breakfast. When he was 10 years old, he managed a team of horses and mowed hay. The days were long, and after dinner the family generally went straight to bed. It wasn’t until his family purchased an Aladdin lamp in the 1930s, he says, that reading was possible after dark. “They advertised it on the radio station we got from Salt Lake City,” he remembers with a laugh. “They said, ‘You can tell a fly from a raisin.'”

There were those who couldn’t stand the isolation of a life in which the nearest town, Malta, was two days away on horseback; those who were moved off their unprofitable land by the Resettlement Administration during the Great Depression; and those who simply found better opportunities elsewhere. Even as his neighbors drifted away, Barnard made a determined choice to stay on the prairie. When I ask him what he likes best about a life that most people would consider difficult, his face lights up. “I guess it’s a challenge,” he says. “Kinda keeps your brain in gear.” Pasture your cattle too high up in the winter, and you will pay for it in the spring. Fail to ensure enough access to water in the summer, and cattle will die.

“You’d go to the neighbors, go through their cattle, see if yours got mixed in. Then you ride out. The only sounds you’d hear would be the glacial gravel. Our skies were clearer then, too. It gives you a sense of reverence. We’re only looking at a small segment of this. You’d see thousands of stars. You just are awed by the power of God. It must be the same thing when the man wrote, ‘How great thou art.'”

It strikes me that Barnard’s reverence for nature and his feeling of communion with something larger than himself are akin to the emotions driving conservationists like Steve Forrest, who hope to turn Barnard’s ranch into a bison range. In the eyes of Barnard and his fellow ranchers, the APF represents outsiders who are interfering with nature, while the ranchers themselves are the true conservationists. The main reason these men and women stick here so stubbornly is that they love the land. Barnard’s father lived here well into his nineties, and three of his four children live within 50 miles of the ranch.

It strikes me that Barnard’s reverence for nature and his feeling of communion with something larger than himself are akin to the emotions driving conservationists like Steve Forrest, who hope to turn Barnard’s ranch into a bison range. In the eyes of Barnard and his fellow ranchers, the APF represents outsiders who are interfering with nature, while the ranchers themselves are the true conservationists. The main reason these men and women stick here so stubbornly is that they love the land. Barnard’s father lived here well into his nineties, and three of his four children live within 50 miles of the ranch.

“The ranchers have been here for 125 years, experiencing everything,” he tells me. As for the APF, Barnard flatly dismisses them as “promoters” who are raising the property assessments of working ranchers by overpaying for land. When I suggest that the reserve will allow tourists to experience the same kind of communion with nature that he so movingly described to me, he laughs. “If the people from back East come out here and roll their windows down, and that 107-degree heat hits them along with a swarm of mosquitoes, then they’re going to get the hell out of here.”

A WEEK LATER, at an Italian restaurant on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, I meet Frank and Deborah Popper, whose article popularized the idea of turning the Great Plains into a bison range more than 20 years ago. A bullet-headed man in his sixties, Frank offers a winning mix of intellectual enthusiasm and neediness, backed by lightning flashes of insight. Deborah, who plays the stable one in the Poppers’ intellectual partnership, brings her husband down to earth with shrewd, practical insights. He was raised in Chicago while she grew up in New York. They finish each other’s sentences and contradict each other with the self-aware rhythms of a married couple enjoying an old soft-shoe routine.

For Frank, the fate of the Great Plains (PDF) is already sealed. “It’s a done deal,” he says flatly. “The only question is how the deal gets done.” The year-by-year fluctuations in the population and economic well-being of rural counties cannot obscure a general downward trend that continues to strip the Plains of inhabitants. “Not only have the pressures on the rural parts of the Plains continued to mount, but there are new pressures that didn’t exist back in 1987,” Frank adds. The Cold War is over. Most of the region’s missile silos and Air Force bases have closed down.

The buffalo commons offers a compelling narrative to describe the mess that human beings have made of the prairie. “This is a decline-and-redemption story, with the buffalo commons being the agent of redemption,” Frank says, as Deborah shoots him a warning glance. “That sounds very pompous,” he adds quickly. “It’s a story of decline insofar as it involves the white settlers, the army who nearly kill off the buffalo,” he explains. “Then you have the Dust Bowl, depopulation; all the environmental indicators fall, like the water table.” Where human settlement has failed, the bison might offer us a fresh beginning.

That promise of redemption is why the Poppers’ idea has attracted the interest and support of famous writers—including Anne Matthews of Princeton, whose 1992 book Where the Buffalo Roam profiled the Poppers and their work and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction, and the novelist Annie Proulx, who included a funny and approving passage about the Poppers in one of her Great Plains novels. In 2004, former Kansas governor Mike Hayden, once a fierce critic of the buffalo commons, publicly endorsed the idea, in part because Kansas is famously short on public land, and most of its counties are losing population. The commons “makes more sense every year,” he told the Kansas City Star in 2009.

Yet it is possible to read the story of the Plains and its settlers another way. When I tell the Poppers about my visit with Gene Barnard, Deborah nods. “In the writing of that ’87 piece, we had a long argument about how to finish it,” she says, turning to her husband. “One of the things that struck me more than it struck you was that there would always be people that would insist on staying.”

Frank nods as he chews through a forkful of pasta. “I am absolutely in awe of the guy,” he proclaims, shifting into enthusiast mode. “An older pioneer type who you don’t see in the Berkshires. I am fascinated by that.”

“It’s a beautiful narrative,” Deborah says, putting her fork down on the table and taking a contemplative sip of white wine. “It’s painful in many ways. Our question is, ‘Can you change the vision and the incentives?’ How do we fix what we screwed up?”

I tell her about the view of the prairie from the top of a buffalo jump near the APF’s base camp, where native hunters stampeded short-sighted bison off a sheer 150-foot cliff. The scene of waving grass, exposed riverbeds, and rolling green land below seemed iconic, like something drawn from the collective human unconscious, I add, as Deborah nods.

Part of the paradox of our appreciation of nature is that we put ourselves in the landscape even as we want to remove ourselves from it, I suggest. Out on the prairie, shadows of passing clouds move across the open spaces just as the landscape itself is shadowed by the human presence, light but always visible in the man-made scars on a nearby rock—perhaps recording a bison kill—or the outlines of a vanished corral.

Removing ranchers from the land to which they have given their lives is no less a deliberate and destructive human act than exterminating bison. An empty landscape that reminds us of the origins of our species is no less a reflection of human imagination and priorities than a ranch. The imagined past is the same as the imagined future. Both are figments of our imagination. The question is, which do we value more?