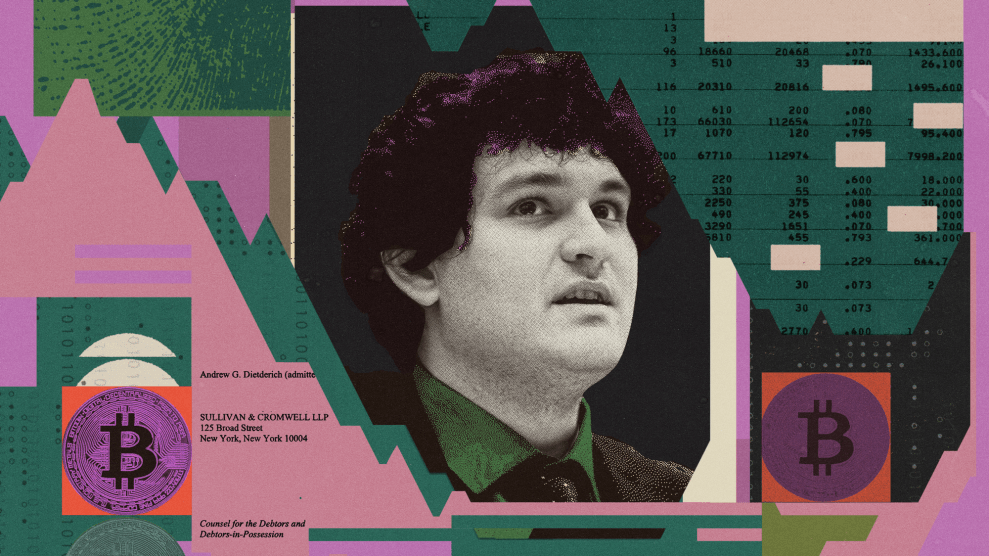

Terrance Roberts, who is now running for mayor of Denver, speaks at a memorial site for 23-year-old Elijah McClain in July 2020.David Zalubowski / AP

Last Wednesday, less than two weeks before the city’s mayoral election, Denver’s East High School experienced its third shooting of the school year.

Almost immediately, Terrance Roberts was getting dozens of texts. The 46-year-old mayoral candidate posted to his Facebook page: “I just heard there was just another shooting at East High School while at Denver Elections,” he wrote. “Check on your babies.”

Austin Lyle, a 17-year-old East High student, had shot and injured two school administrators while they were conducting a routine safety pat down (a daily search prompted by Lyle’s past behavior). His body was found Wednesday evening, 50 miles away from Denver, with a self-inflicted gunshot wound. In February, a few weeks earlier, 16-year-old student Luis Garcia was shot in a car outside East High; he died 17 days later. Last September, just two weeks into the school year, 14-year-old student RJ Harding was shot outside of a recreation center next to the school. With Denver Public Schools closed for a “mental health day” last Friday, East High students and teachers rallied outside the state capitol for the second time this year, calling on lawmakers to take immediate action on gun violence.

Out of the 17 candidates on the ballot, Roberts is probably the most familiar with youth violence in Denver. The conversation that is now at the forefront of the Mile High City’s mayoral race is one he’s been a part of for decades.

“I am the school-to-prison pipeline,” Roberts tells me. “There’s no political candidate with this kind of experience.”

Roberts was shot in the back in 1993 during the city’s infamous “summer of violence,” when local media’s nonstop crime coverage led to punitive legal and policy reforms for juveniles and, according to The New Republic, created “an express lane for children into adult prisons.” As TNR explained, “Those most affected were Denver’s Black youth, who made up a disproportionate share of the 46 people sentenced to life in the ’90s for crimes they committed as children.”

In 1990, at age 14, Roberts had joined a gang in Denver’s Northeast Park Hill neighborhood, which led to his incarceration, on-and-off, for 10 years. His two years spent in solitary confinement, reading Malcolm X and studying the Black Power movement, inspired him to return to Park Hill after his release, where he founded Prodigal Son, a youth violence intervention initiative. His work is also the subject of a recent documentary, The Holly, that follows Roberts’ activism in the midst of the rapidly gentrifying section of Denver. The film won the audience award at the Denver Film Festival.

His background has been a blessing and a curse in the mayoral race, according to Roberts. Going up against career politicians has been difficult, but his unorthodox past, he believes, is his advantage. His lived experience has informed his platform, which centers on addressing poverty, building public social housing, establishing a public banking system, and bolstering youth services. Earlier this month—during a local TV interview with Roberts—9News anchor Kyle Clark said that of all the candidates he’d interviewed, Roberts was the only one to mention poverty.

“People think of Detroit, Chicago, or Los Angeles as having poverty and gangs,” Roberts tells me. “But we have it right here. Poverty is showing up in the ways it always has.”

Recent polling suggests there’s no clear frontrunner in the April 4 race, with every candidate—including Roberts—struggling to break out of the single digits and secure a spot in the June runoff. Voters rank crime, housing, homelessness, education, and police violence as the top issues facing the city.

Roberts is critical of how the city’s $1.6 billion general fund budget is currently being allocated. He’s particularly focused on the small percentage of the budget that is allotted to housing, which he argues is more important for public safety than policing is. If he wins, Roberts promises to audit law enforcement spending. Funding for the Department of Public Safety, which includes the police, sheriff, and fire departments, currently represents 36 percent of the budget—more than any other city department. (Denver’s school district, which receives funding from city property taxes, the state of Colorado, and the federal government, is not included in the city’s budget.)

Roberts is also concerned about the Denver school board’s quick decision after the latest East High shooting to put police known school resource officers (SROs) back into schools, reversing the board’s prior decision in 2020 to remove them. (The board has asked the current mayor to assist with “external funding” for SROs through June.) SROs, Roberts argues, have a track record of criminalizing youth and haven’t been shown to be effective at preventing school shootings. Having officers in school effectively created a school-to-prison pipeline, he says. “Kids, 18-year-olds, were getting sent to the county jail for fighting tickets,” Roberts adds. But he says he’ll listen to what the kids say they need. “Let’s focus on letting the youth say what they want and feel. I trust their minds and ideas around the issue of solutions to gun violence,” he wrote on his Facebook page.

Many young people in Denver know Roberts from his organizing and protest leadership in 2020 following the police killing of Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old in Aurora, Colorado. But the youth he worked with at Prodigal Son in 2004 are no longer kids; they’re voters. Some of them are even working on the campaign.

“Some of those kids are school teachers now, they’re 24 or 25,” he tells me. Instead of playing basketball with him, they’re helping him get out the vote.

While Roberts is hopeful that his 20 years of community organizing has gained him enough name recognition to advance to an all-but-certain runoff, he says it’s more important that his ideas come to fruition.

“If I lose,” he says, “let’s just hope someone steals my platform.”