AndreyPopov/iStock/Getty

There’s one trial that Buta Biberaj will never forget. Biberaj, a former defense attorney, remembers how Virginia jurors in 2017 requested 132 years of prison for a man who stole car tires. The jurors may have been unaware that taxpayers could pay more than $25,000 a year to keep someone incarcerated—so by proposing their sentence, they were also suggesting that society fork over $3 million. For tires.

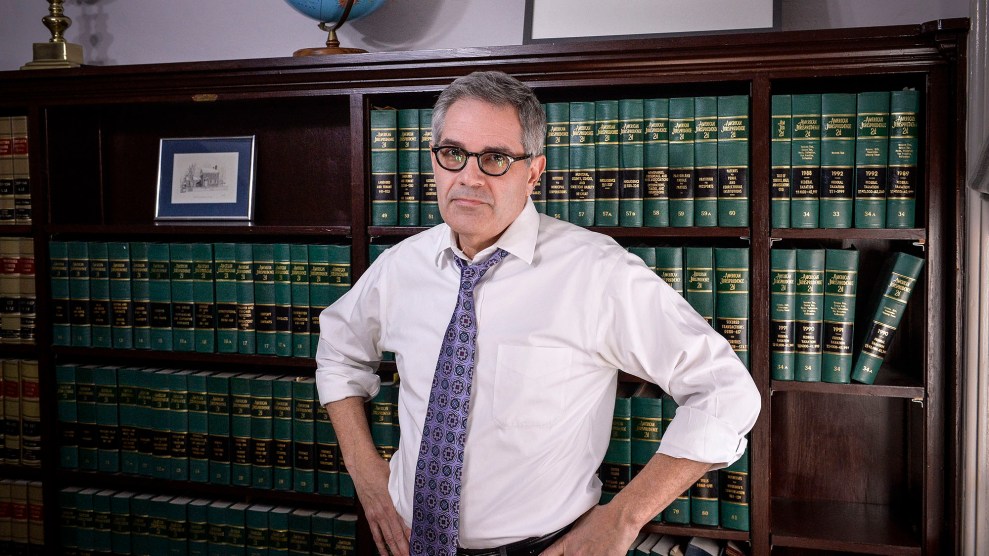

Last week, Biberaj started her term as district attorney in Virginia’s Loudoun County. As part of a wave of progressive candidates that swept district attorney elections in Virginia in November, Biberaj is calling for changes that reformers elsewhere have championed, like ending cash bail and letting marijuana crimes go. But she’s also touting a proposal that goes a step beyond what most liberal district attorneys have floated: She wants courts to grapple with the financial toll of incarcerating people.

Normally, if someone commits a felony like rape or murder, a prosecutor from a district attorney’s office tells a jury or judge why the victim deserves to see the offender locked away. Prosecutors are often evaluated by the number of convictions they receive and the types of lengthy sentences they secure, with some touting their toughness to win reelection.

Biberaj, during her 25-plus years as a defense lawyer and more than a decade as a substitute judge, came to believe that the sentencing process is flawed. So now as district attorney, she wants her office to tell juries exactly how expensive it is to send people to prison. “If we don’t give them all the information, in a certain way we are misleading and lying to the community as to what the cost is,” she said in an interview before the election.

Biberaj is not the first prosecutor to suggest such a policy. In 2018, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, one of the country’s most famous progressive prosecutors, launched a similar experiment. Shortly after his election, he instructed his office’s attorneys to tell judges how much recommended prison sentences would cost, noting that a year of unnecessary incarceration in the state rang in at about $42,000—around the salary of a new teacher, police officer, or social worker. “You may use these comparisons on the record,” he told them. Chesa Boudin, the former public defender elected as district attorney in San Francisco in November, says he plans to implement a similar policy after taking office this week.

Americans pay tens of billions of dollars a year for state prisons, despite declining crime rates. But historically, prosecutors and judges haven’t had to think about these hefty costs. That’s due to how the system is set up: For state cases, prosecutors usually work at the county level, but when they imprison someone for a felony, the county doesn’t foot the bill for it—the state does. “This blank check on admissions,” as the policy institute Brennan Center for Justice put it in an article about reducing prison costs, “creates a tragic paradox: It is easier and cheaper for the county if a prosecutor sends someone to state prison” than it is to “divert them into community-based alternatives” like probation or drug treatment programs that are funded locally. “Combined with office cultures that reward convictions and long sentences, prosecutors are routinely incentivized to perpetuate mass incarceration,” the Brennan report stated.

Krasner wanted to break that pattern. “What he’s doing in terms of asking prosecutors to talk about the cost of incarceration is incredibly innovative,” Lauren-Brooke Eisen, a former prosecutor who now works at the Brennan Center, says. If more district attorneys followed suit, she adds, it could go a long way toward lowering prison populations.

But so far, other than Biberaj and Boudin, the idea hasn’t caught on widely. While more progressives are running, about 80 percent of prosecutors go unopposed in elections, meaning that many tough-on-crime district attorneys maintain their seats.

And some judges don’t want to know how much a prison term will cost. They argue that money has no place in decisions about punishment and justice. Choosing a sentence, they say, should involve weighing the specific situation and needs of the offender and victim, irrespective of budget. And if elected judges feel pressure to save money for taxpayers, it could skew their opinions, argues Chad Flanders, a professor at Saint Louis University School of Law. “Asking judges to make budgetary decisions in sentencing is just another way of asking them to be politicians,” he wrote in a paper on the subject in 2012. Some judges in Philadelphia have asked Krasner’s attorneys not to share the cost data with them.

The idea of sharing costs with courts has long been mired in controversy. About a decade ago, the state of Missouri encouraged judges to think more about finances. But the experiment was met with protest and quickly unraveled.

In 2010, Michael Wolff, then a justice of Missouri’s Supreme Court and chair of the state Sentencing Advisory Commission, began offering cost data as part of the presentencing reports that judges could access. (The reports included recommended sentences for a case, the cost, and information about recidivism risks). Tallying the price of sentences seemed sensible to him, especially because he knew prison wasn’t just expensive, but also likely to increase a person’s chances of committing more crimes later. “It was a way to counteract the trend of thoughtlessly or automatically sending people to prison as your default punishment,” Wolff told me recently.

But not everyone was on board with Wolff’s plan. “It drove the prosecutors crazy,” he said. The presentencing reports made it harder for them to influence the narrative and the outcome of a case. Robert McCulloch, then chief prosecutor in St. Louis County, who would later become famous for not securing an indictment against the police officer who killed the teenager Michael Brown, pushed Wolff to stop giving this financial data to judges. “Justice isn’t subject to a mathematical formula,” McCulloch told the New York Times in 2010. Along with the Missouri Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, McCulloch publicly opposed the policy. In 2012, lawmakers passed a law that stopped the sentencing commission from sharing specific cost data.

In 2013, Vermont lawmakers considered a bill that would have required judges to consider the cost of sentences, but the measure failed. In Suffolk County, Massachusetts, reformist district attorney Rachael Rollins expressed support for Krasner’s policy during her campaign in 2018, telling Mother Jones she hoped to implement something similar if elected. But while she has since enacted other reforms, like declining to press charges for certain low-level crimes, she hasn’t required her prosecutors to state financial costs in court. Neither has Wesley Bell, the reformist district attorney who ousted McCulloch in 2018. Wolff is now his adviser; he says other goals like bail reform have so far taken a higher priority.

Even Krasner’s office has run into some trouble. “Of the different reforms we have put in place, the cost stuff hasn’t been the highest thing on our agenda,” Ben Waxman, his former communications chief, told me last April. He said some judges didn’t want to see the data. “Our approach has been not to go to the mattresses over that particular thing. Which doesn’t mean it still isn’t being done in some courtrooms—but it’s certainly not being done in all courtrooms.”

Not all judges want to think about finances. One Philadelphia judge reportedly threatened to hold a prosecutor in contempt of court if costs were brought up in his courtroom one more time. “Philosophically, I don’t like the thought that when a judge makes a decision of who needs to go into prison, that money should ever enter into that equation,” says Judge Howard Harcha, on the common pleas court in Portsmouth, Ohio, a state that has also tried to get judges thinking more about money.

Even if progressive prosecutors don’t end up leading the charge, there is something states can do to make judges consider the price of their recommended punishments. A couple of them are already adopting surprisingly simple solutions.

In 2018, Ohio started charging some counties a penalty—$72 a day—for every person they send to prison for low-level felonies like vandalism or drug possession. That’s about the average cost of locking someone up, including things like guards’ salaries and heating expenses, and much more than the roughly $10 a day it takes to monitor someone on probation. As a result, judges know the financial toll their chosen sentence will have on the county. They can choose to send people to the county jail but are encouraged to prioritize cheaper options like probation or drug treatment—programs that have the benefit of keeping people in their communities and helping them overcome obstacles that may have driven them to crime in the first place. The state provides counties with grants to develop these community-based rehabilitation programs. The program is so far diverting about 1,470 people from the prison system annually, according to a corrections department spokesperson.

It’s too soon to know what the impact of Ohio’s program, called T-CAP, will be, but we can look to another state for encouragement. In 2011, Illinois also began handing out grants to counties that developed alternatives to incarceration, and threatening a penalty to those that failed to reduce their prison admissions for certain populations (like people suffering from mental illness or addiction). From 2011 to 2017, the state gave $25 million for things like drug treatment and restorative justice programs as part of this program, called Adult Redeploy. The funding helped keep 3,000 people out of prison and in their communities, saving the state about $20 million during that period, according to Mary Ann Dyar, the program’s director.

But there are still critics. In Portsmouth, Ohio, which has been described as ground zero for the opioid epidemic, Judge Harcha works with many defendants accused of drug crimes, and thinks the threat of prison can be useful for people who don’t stick with court-ordered drug treatment. “Everyone wants to see these people get over their addiction and start doing better,” he says. “Sometimes the harsh treatment of sending someone to prison is the only thing that’s going to maybe send them on the right path in the future.”

In Winnebago County, Illinois, Judge Janet Holmgren argues the Adult Redeploy program actually gives courts more discretion, because it offers them extra money for diversion programs, allowing them to assist more people: “We’re more willing to accept people with extensive criminal histories that in the past we might have declined because we had limited resources.” Jay Scott, the state’s attorney in Macon County, Illinois, agrees. In the past, he says, with “so many people that were committing low-level felonies, the only option we had was sending them back to prison. It was a revolving door.”

W. David Ball, a law professor at Santa Clara University, has a more radical idea: What if counties, based on their respective levels of violent crime, received grants to work toward safer communities, with the freedom to spend that money however they wanted? And then what if they were charged for the full cost of every person they sent to state prison—not just the low-level felons? It’s never been tried, but John Pfaff, a Fordham law professor and author of Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, says the idea could especially benefit low-income, high-crime jurisdictions. Rather than charging counties the average cost of a prison stay, like Ohio does, Pfaff suggests charging the marginal cost per prisoner, which is normally less because it doesn’t include the price of guards’ salaries or heating and cooling.

All these scenarios are examples of what criminal justice geeks refer to as “performance incentive funding”: essentially using finances to change the behavior of local officials, whether prosecutors or judges. California has also experimented with performance incentive funding: It pays grants to counties that reduce the number of people serving time in prison for probation violations. In 2011, after a Supreme Court decision, the state also ordered counties to incarcerate more people with felony convictions locally in jails, funded by counties. There are downsides to this arrangement—jails don’t have the same educational programs as state prisons, for example, and they experience less oversight. But, as a result of this policy and other reforms, California’s prison population has dropped so dramatically that it accounts for nearly half of the country’s total decline in prisoners since 2010, according to Pfaff.

At the federal level, Congress could pass the Reverse Mass Incarceration Act, which authorizes $20 billion over a decade to states that cut prison populations by a certain amount without any noticeable uptick in crime. The bill, which was proposed last year by Sen. Cory Booker, has been advertised as an antidote to Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, which gave states billions of dollars to build prisons. “The idea is let’s do the opposite,” says Eisen, though the measure could be a hard to pass, given a lack of Republican support. Sen. Kamala Harris, a former prosecutor, has suggested lawmakers could go further by using “budgetary incentives to help reorient prosecutorial practices” toward “a culture of reducing mass incarceration.”

Of course, the financial toll of incarceration isn’t necessarily the most significant toll. “What do we gain from not sending one person to prison? It’s not really that reduction in $7,000 a year in tax spending. It’s that this person doesn’t get raped, he doesn’t get HIV, his child doesn’t suffer the stigma of a father who’s in prison,” says Pfaff. “When people return from prison, they tend to be sicker, they have a harder time finding a job. All these things are the real costs.” And they can increase the chances of a person reoffending.

When discussing the pros and cons of a sentence, “it’s really important it’s not dollar for dollar,” adds Eisen from the Brennan Center, and that decision-makers emphasize these social costs, not just budgets. But getting prosecutors and judges to think about money, she says, can encourage them to become less punitive with their sentencing, which in turn helps people avoid prison and its other negative effects.

Indeed, Krasner has also urged prosecutors during sentencing hearings to break down the social costs and benefits of incarceration, like what impact it will have on victims or defendants and their families. District attorneys like Rollins in Massachusetts and Bell in Missouri have encouraged their attorneys to think more about these factors, too, and San Francisco’s Chesa Boudin says he plans to do so as well. “It may not be that they are sitting down and doing a dollars and cents calculation, but many are recognizing that engaging the justice system has a set of consequences, and we should be willing to justify the damage that results by an overriding public safety interest,” says Miriam Aroni Krinsky, who trains prosecutors through her organization Fair and Just Prosecution.

In the end, a court’s choice of punishment will be complex, says Gary Oxenhandler, a retired circuit court judge in Missouri. But having more information about the costs, including financial ones, shouldn’t hurt: With decision-making, “knowledge is power,” he says. “Every little bit of information helps.”