A window at the Cook County jail complex.Scott Olson/Getty

From the earliest days of the pandemic, criminal justice experts and advocates warned that jails could rapidly become major sources of infection as staff and inmates enter into crowded and unhygienic conditions, then return to their communities outside. Now, research has revealed just how significant a role the Cook County Jail—one of the country’s largest—has played in spreading the coronavirus: Nearly 1 in 6 COVID-19 cases identified in all of Illinois by mid-April was associated with people cycling through the jail, according to a new analysis.

The paper, published Thursday in the journal Health Affairs, used booking, release, and infection data from the Cook County Jail and coronavirus case counts from the Illinois Department of Public Health to analyze the relationship between “jail cycling”—high rates of people being arrested and released—and coronavirus infection rates across different neighborhoods. COVID-19 case rates, the authors concluded, were “significantly higher” in zip codes where many people were cycling in and out of jail. Jail cycling was even more strongly associated with a zip code’s COVID-19 case rate than race, poverty, public transit utilization, or population density.

“Although we cannot infer causality, it is possible that, as arrested individuals are exposed to high-risk spaces for infection in jails and then later released to their communities, the criminal justice system is turning them into potential disease vectors for their families, neighbors, and, ultimately, the general public,” the authors wrote. Given just how disproportionately Black neighborhoods are policed, they added, the powerful role of jails in spreading infection “may bear partial responsibility” for the wide racial disparities seen in coronavirus case rates. Black residents comprise 30 percent of the population in Chicago, but accounted for 52 percent of the city’s COVID-19 cases as of early April, according to the Associated Press. (As of June 4, the city was reporting that 30 percent of its coronavirus cases were among Black residents; 48 percent were among Latinx residents.)

Every person who cycled through the jail translated to 2.149 new cases of COVID-19 in the broader community, explains co-author Eric Reinhart, a PhD student at Harvard University and medical student at the University of Chicago. This means that the 2,129 people released from Cook County Jail in March were associated with an additional 1,938 community infections in Chicago, and 4,575 community infections in all of Illinois by April 19. Since then, the numbers have likely only grown. “There is a cascade effect,” Reinhart says in an email. “Each of these infections subsequently multiplies into more cases with more people.”

Reinhart argues that the study’s results reveal consequences of a “a much broader structural problem of hyper-aggressive arrest practices and mass incarceration across the country.” But the particular role of the Cook County Jail in spreading infection should come as no surprise. As my colleague Samantha Michaels reported in April, a federal lawsuit seeking the release of inmates at higher risk for COVID-19 described the impossibility of following public health guidelines inside:

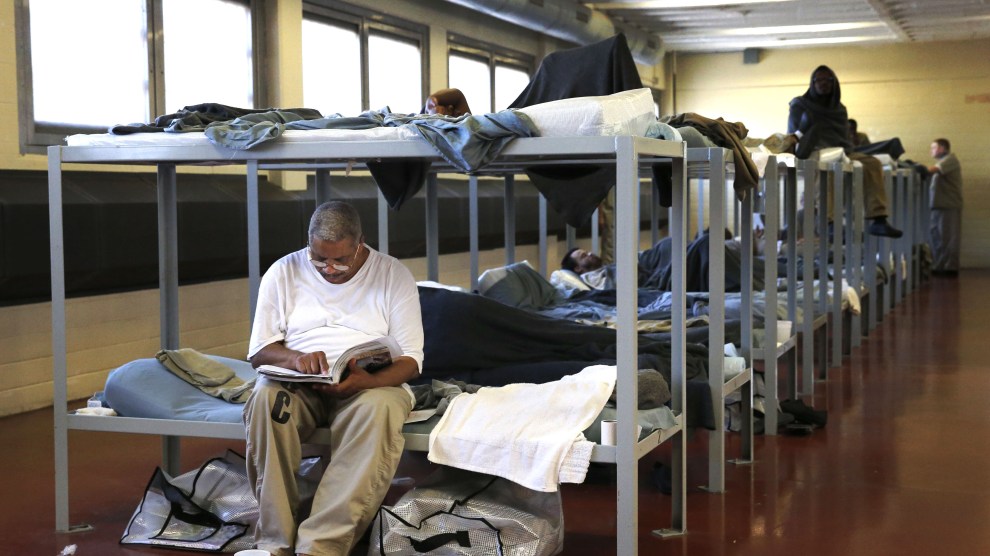

The class-action lawsuit includes Anthony Mays, a 38-year-old with diabetes who was referred for an evaluation for a heart condition when COVID-19 hit the jail. He’s housed in an open-dorm setting where dozens of beds are spaced about two feet apart, and multiple detainees on the tier have been removed after testing positive. Kenneth Foster, another plaintiff, also lives in a dorm setting and has stomach cancer, lung sarcoidosis, high blood pressure, asthma, and bronchitis. Other inmates named in the suit have Hodgkin lymphoma and blood clots; one man’s throat was reconstructed after he was shot.

“Inside accounts from Jailstaff, detainees, and…medical personnel paint a picture of an unfolding disaster,” states the lawsuit, filed by civil rights attorneys who argue the county has violated people’s constitutional rights by failing to protect them from disease at the jail. The roughly 4,700 detained men and women at the Cook County Jail share phones, toilets, sinks, and showers, often with limited access to soap and hot water. Surfaces are infrequently washed, according to the suit, and people are quarantined in group settings, not individual cells, increasing the chance of infection. “It’s a lot of people, who were in a very intimate physical space with someone who is positive,” says Stephen Weil, one of the attorneys.

For the past several months, the Cook County Jail had been reducing its population in response to the pandemic. But over the past week, the trend has reversed, as police arrest large numbers of people during protests against police brutality and systemic racism. In May, about 4,000 people were incarcerated, according to local news station WTTW. By Thursday, that number surpassed 4,500.

Update, Friday June 5, 8:00 p.m.: In a statement, the Cook County Sheriff’s Office argued that the Health Affairs study was based on outdated information. “As a result of our interventions, cases at the jail have dropped precipitously over the past month,” said assistant director of public relations Kathleen Carmody. At present, the jail has identified 36 detainees and 42 staff members who are positive for COVID-19, according to Carmody; 511 additional detainees who have recovered from COVID-19 were still in custody as of Thursday.