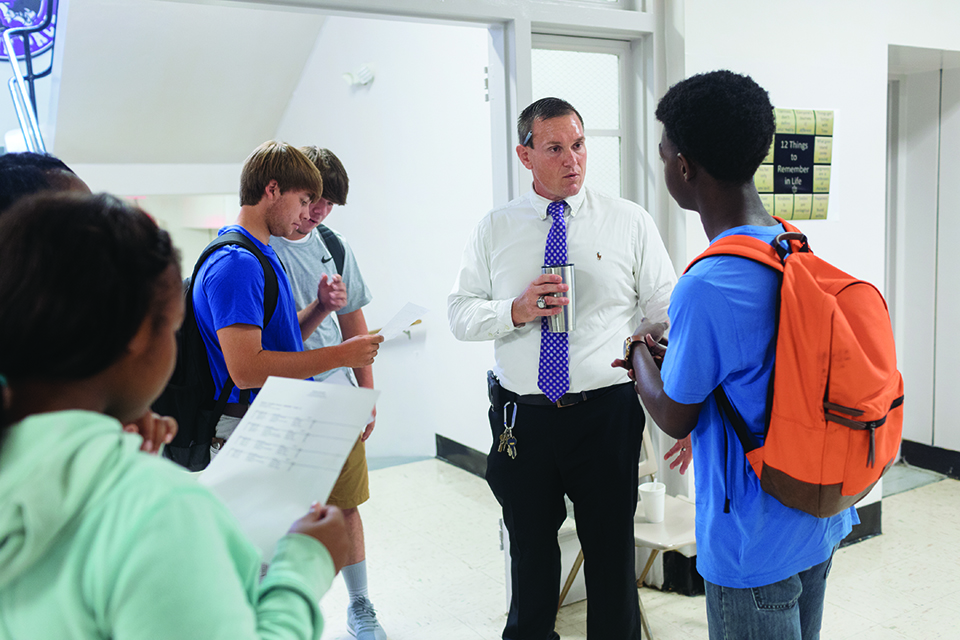

There was a time, about 60 years ago, when many of principal Randy Grierson’s students wouldn’t have been allowed to step foot in the building that now houses Cleveland Central High School. But on a morning in August, there they were, a gaggle of goofy teens joking and chattering in the halls, back to school after a long, hot Mississippi summer. Grierson greeted them with a stare, followed by a grin forming on his square-jawed face. Some people had expected trouble—maybe fistfights, maybe parents pulling their kids out of school, who knows? Even Grierson, optimistic by nature, had concerns. “Is everybody okay?” he said, stepping into a classroom filled with a mix of black and white students. “Is everybody’s schedule—is everything good on their schedule?”

“No!” a few students shouted almost in unison, before the mood lightened with an explosion of collective laughter.

Cleveland Central High School is the latest attempt, after years of litigation, to desegregate Mississippi’s school districts. The town of Cleveland, home to 12,000 people, hosts tiny Delta State University and the recently built Grammy Museum, a 27,000-square-foot facility smack-dab in the birthplace of the blues. In the center of town, a tree-dotted promenade sits where train tracks once split Cleveland in two—whites lived on the west side, African Americans on the east side—and the town’s schools long reflected that divide.

Students graduate from Cleveland High School in Cleveland Mississippi on May 21, 2017. This is the last graduating class from Cleveland High, the historically white school in Cleveland Mississippi.

As a result, in May 2016 a federal judge ordered the town to merge its two high schools. Cleveland High, about 45 percent white, and East Side, 100 percent black, would become one. The district appealed the ruling, but in January the school board announced it would drop the challenge, ending a costly legal battle. In August, more than 900 of the district’s students started taking their classes at the old Cleveland High campus, now rechristened Cleveland Central High School. The East Side campus became the town’s middle school. After its opening in 1906, Cleveland High School served white students, while East Side, formerly known as Cleveland Colored Consolidated High School, served only black students. A judge ordered the district to desegregate in 1969—15 years after Brown v. Board of Education—but in 2011, a Justice Department review found that the district had “failed to make good faith efforts to eliminate the vestiges of its former dual school system.”

“It’s just one of those things we’ve gotta keep building on,” Grierson told me when I met him during the first week of class. Before this, he’d been the principal at East Side High for six years, the school’s first and only white principal. Born in 1977 and raised in Pascagoula, Mississippi, he’d expected the melding of East Side and Cleveland High to be tense. But with the exception of an altercation between two students, the first few days had gone better than anyone could have imagined. Still, he knew, it was too early to judge the success or failure of the merger. “It’s not going to happen in a day; it’s not going to happen in a week,” he said. “It takes time. We gon’ keep pushing on.”

After Brown v. Board of Education paved the way for a federal crackdown on segregation, schools in the South became the least segregated in the entire country, according to UCLA’s Civil Rights Project. But court oversight of school districts under desegregation orders has diminished steadily since then, the result of a series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1990s that gave increasing authority to states over the federal government. Meanwhile, there’s been an overall decline in white enrollment at public schools, with many white parents sending their children to private schools. Scores of black and Latino students have also decamped for charters. The result nationwide, and especially in the South, has been massive resegregation. More than 1 in 3 black students in the southeastern United States today attend schools where at least 90 percent of their peers are minorities, up from 24 percent in 1988. The Justice Department, in turn, is overseeing desegregation cases at 172 school districts across the country. Forty-two of those districts are in Mississippi.

In August, the kinks of the merger approach were still being worked out at Central. The student body had swelled from 592 students to 920. The flow of morning traffic spiked and buses ran late. “Look, I’m new to this,” Grierson told a colleague as they discussed where parents should drop off their kids. “You tell me if there’s a better way to do it, we’ll do it.” Throughout first period, he stopped by classroom after classroom, making a point to tell students, “Good morning,” just as he had when he oversaw East Side. Authorities have tried numerous strategies besides school mergers, but all have failed. In 1989, a court ordered the Cleveland school district to bus students between the two high schools for shared classes; some Advanced Placement and college-credit courses were introduced at East Side, forcing Cleveland High students to travel across town if they wanted to take them. Then, in 2013, a judge ordered the district to implement a “freedom of choice” plan that allowed students to enroll wherever they wanted. But while black students signed on at Cleveland High, no whites chose to attend the predominantly black school.

“I think it’s important to tell them something positive,” Grierson said. Many of the district’s students, black and white alike, grapple with poverty and subpar academic performance. More than two-thirds of them qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. During the 2015-16 school year, 14 percent of East Side students were proficient in math and 16 percent were proficient in reading, compared with less than 5 percent of Cleveland High students in math and 29 percent of them in reading. “A lot of these kids,” Grierson said, “do not have anything positive told to them in the mornings.”

The day before I met up with Grierson, I stopped by New St. Phillip Church, where black residents who’d pushed for consolidation were having a conference call with a Justice Department official eager to hear how things were going. A group of six mostly middle-aged and elderly folks leaned against pews and closed their eyes as the Reverend Edward DuVall opened the meeting with a prayer. “Lord, I would ask you to help us get the best resources for our kids,” DuVall said. “We hope in our lifetime that they have a state-of-the-art school.”

For nearly a decade, this group had spoken out in community meetings and in court against school segregation. They huddled around a cellphone speaker as the Justice Department’s Aziz Ahmad explained that by the end of fall, DOJ officials would visit the district, potentially for homecoming, to see how things were going. “Yesterday, for the first time in the history of Cleveland, they opened desegregated high schools and middle schools,” Ahmad said. “This is really historic. I know there’s still a lot of work to do, but we still see this as an important, consequential victory.”

Tamara Reid graduates from East Side High School in Cleveland, Mississippi on May 21, 2017.

Attendees cheers during the graduation at Cleveland High School in Cleveland Mississippi on May 21, 2017.

Ahmad’s voice was upbeat, but whether Trump’s Justice Department will enforce Obama-era efforts to desegregate schools is uncertain. And Education Secretary Betsy DeVos favors school choice programs, which she says lead “to more integrated schools,” despite evidence to the contrary.

As the meeting came to a close, Kierre Rimmer, a 1993 East Side graduate and head of a local youth group, asked DuVall if he could address the room. “There isn’t an east side or west side of town anymore,” Rimmer said. “This is Cleveland, Mississippi.” He talked about his eight-year-old daughter, who attends elementary school. “She doesn’t know anything about the east side or the west side of town. And that’s how we should be now. It took us 60 years to get here, but if you start holding onto terms like east and west side, you still holding onto that mess.”

Across town at the Central High football field, Rimmer’s words seemed to ring true. Under the sweltering heat, dozens of players in full pads broke off for drills on the field next to Mickey Sellers Stadium. They’d been playing together since spring practice at the end of April; to promote team bonding, head coach Ricky Smither had made Cleveland High and East Side players share lockers at the field house. As of this past weekend, they were 9-0.

Students who graduated in 1967 return to East Side High School graduation for their 50th anniversary. 2017 is the last graduating class from East Side High School, the historically black school in Cleveland Mississippi.

Skylar White, 18, waits in the air-conditioned doorway after graduating from East Side High School in Cleveland, Mississippi on May 21, 2017. White had decorated her cap to say “Strong Black Woman” for graduation.

After practice, players peeled off their gear and dispersed into cars. Junior Jacob Dodd, who lingered next to a white pickup truck in the parking lot outside the field house, told me he saw his spot as a starting center—and as one of the few white players on the team—as “an honor.” “I couldn’t tell any separation between us,” Dodd said. “We were all mingling together well. There was no East Side or Cleveland High talk.”

Senior Rashad Harbin, who’d previously attended Cleveland High, told me he was excited to graduate alongside kids he knew from East Side. “Now that we all together,” he said, “it’s like a big family reunion.”

Cleveland Central High School football team practices after the first day of school in Cleveland, Mississippi on August 7, 2017.

Randy Grierson, the head principal of Cleveland Central High School, greets students on the second day of school in Cleveland, Mississippi on August 8, 2017.

The family, of course, isn’t without its discontents. In court, the district had warned that consolidation would prompt white flight, and data provided to Mother Jones confirms that 56 high school students transferred in advance of the merger, including 13 students who left to attend nearby private schools. Meanwhile, a black student filed a federal lawsuit this summer, saying she would have been Cleveland High’s first black sole valedictorian had the school not made her share the honor with a white student. The suit prompted an ugly backlash. “You niggers and your self-entitled actions make me sick,” a man wrote in a Facebook message to the student. “You shouldn’t even be at the same school as white people!” But these protests, so far, are mostly anomalous. Mike Saxon, a 1989 Cleveland High graduate whose son is a senior at Central, better reflects the town’s mood. He told me that even though the consolidation still bothered him a little, he was coming around to it. “It is what it is,” he said. “It’s change. You’ve gotta go with it.”

Grierson, also known as “Dr. G”, meets with students during the first weeks of class at Cleveland Central High School. Cleveland Mississippi had two high schools, one that was historically black and the other that was historically white.

Kloby Smith, 14, and Alexus Peauy, 16, pose for a portrait.

Cleveland Central High School football team practices after the second day of school in Cleveland, Mississippi on August 8, 2017.

Reverend Edward DuVall at his church, Homestretch Church in Cleveland, Mississippi on August 9, 2017.