helenecanada/iStock

“The one place where a man ought to get a square deal is in a courtroom, be he any color of the rainbow, but people have a way of carrying their resentments right into a jury box.” —Lawyer Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird

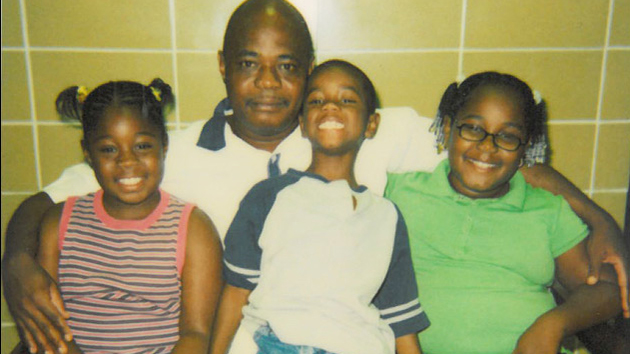

In April 2005, nearly eight years after Kenneth Fults was sentenced to death for kidnapping and murdering his neighbor Cathy Bounds in Spalding County, Georgia, one of the trial jurors made a startling admission under oath: He’d voted for the death penalty, he said, because “that’s what that nigger deserved.”

It shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise, given the circumstances—a black man admitting to the murder of a white woman in the deep South—that some white jurors might secretly harbor racist views. The surprising part was that this juror, Thomas Buffington, came right out and said it. And what should have been the most surprising development of all (alas, it wasn’t) came this past August, when a federal appeals court, presented with ample evidence, refused to consider how racism might have affected Fults’ fate.

In fact, state and federal courts have routinely avoided the evidence and consequences of racism in the criminal-justice system. (See “5 Death Penalty Cases Tainted by Racism.”) Consider one of the most famous examples, the 1987 Supreme Court case of McCleskey v. Kemp, in which lawyers for Warren McCleskey, a black man sentenced to death for killing a white police officer, presented statistics from more than 2,000 Georgia murder cases. The data demonstrated a clear bias against black defendants whose victims were white: When both killer and victim were black, only 1 percent of the cases resulted in a death sentence. When the killer was black and the victim white, 22 percent were sentenced to death—more than seven times the rate for when the races were reversed.

It wasn’t just jurors who were biased. Prosecutors sought the death penalty for black defendants in 70 percent of murder cases when the victim was white, but only 15 percent when the victim was black.

The Supreme Court was less than impressed with all of this. Justice Lewis Powell, in a 5-4 majority opinion he would later call his greatest regret on the bench, wrote that McCleskey could not prove that “the decisionmakers in his case acted with discriminatory purpose.” In short, evidence of systemic racial bias had no relevance in individual cases. Further on, Powell got down to his true concern: “McCleskey’s claim, taken to its logical conclusion, throws into serious question the principles that underlie our entire criminal justice system.”

Justice William Brennan dissented with one of the most memorable statements of his iconic career: “Taken on its face, such a statement seems to suggest a fear of too much justice.” He went on: “The prospect that there may be more widespread abuse than McCleskey documents may be dismaying, but it does not justify complete abdication of our judicial role.”

Georgia executed McCleskey in 1991, but the McCleskey rationale—which the New York Times labeled the “impossible burden” of proving that racial animus motivated any particular prosecutor, judge, or jury—has been used by dozens of courts to reject statistical claims of discrimination in capital cases, even though today’s numbers are not much better.

The Fults case was different, though. Here was an actual juror explaining his decision to impose the death sentence through a blatantly racist lens. It was precisely the sort of evidence the Supreme Court claimed was lacking in the McCleskey case. So why has Kenneth Fults not been granted a new sentencing?

Justice Powell’s concerns are understandable. After all, what part of the criminal justice system is untouched by racism? Some death penalty critics, in fact, view capital punishment as a direct descendent of lynching.

The phrase “legal lynching” first appeared in the New York Times during the infamous 1931 Scottsboro Boys trials, in which nine black youths were charged with raping two white women in Alabama. Their lack of counsel, coupled with the explicit exclusion of black jurors, led the Supreme Court to intercede twice and reverse convictions.

It’s hard to read those opinions today without feeling a sense of horror. Within two weeks of the alleged crime, eight of the nine young men had been sentenced to death in three separate trials by the same jury. Although there was no shortage of black men in Scottsboro County who were legally eligible to serve on juries, there was no record of any of them ever serving on one. Perhaps most remarkably, none of the defendants had a lawyer appointed to represent him until the morning of trial. In 2013, more than 80 years after the arrests, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles posthumously pardoned the three Scottsboro Boys whose convictions still stood.

We have not come nearly as far from these outrages as you might think. People of color are still dramatically underrepresented on juries and grand juries, even though excluding people based on race is illegal and undermines “public confidence in our system of justice,” as the Supreme Court put it in 1986. Prospective black jurors are routinely dismissed at higher rates than whites. The law simply requires some rationale other than skin color.

“Question them at length,” a prominent Philadelphia prosecutor suggested to his protégés after the Supreme Court banned race as a reason for striking jurors. “Mark something down that you can articulate at a later time.” For instance, a lawyer might say, “Well, the woman had a kid about the same age as the defendant, and I thought she’d be sympathetic to him.”

In 2005, a former prosecutor in Texas revealed that her superiors had instructed her, if she wanted to strike a black juror, to falsely claim that she’d seen the person sleeping. This was just a dressed-up version of the Dallas prosecution training manual from 1963, which directed assistant district attorneys to “not take Jews, Negroes, Dagos, Mexicans, or a member of any minority race on a jury, no matter how rich or how well educated.”

The 1969 edition of the manual, used into the 1980s, promoted a more subtle brand of stereotyping, noting that it was “not advisable to select potential jurors with multiple gold chains around their necks.” But it hardly mattered: Overt, covert, or in between—the result was the same.

Virtually every state with a death penalty has dealt with accusations that black jurors have been improperly kept off juries. During the 1992 death penalty trial of a defendant named George Williams, for example, a California prosecutor dismissed the first five black women in the jury box. “Sometimes you get a feel for a person,” he explained, “that you just know that they can’t impose it based upon the nature of the way that they say something.” The judge went even further, noting that “black women are very reluctant to impose the death penalty; they find it very difficult.” In 2013, the California Supreme Court ruled that these jury strikes were not race-based, and deemed the judge’s statement “isolated.” Williams remains on death row.

After North Carolina passed its Racial Justice Act, a 2009 law that let inmates challenge death sentences based on racial bias, a state court determined that prosecutors were dismissing black jurors at twice the rate of other jurors. The probability of this being a race-neutral fluke, according to two professors from Michigan State University, was less than 1 in 10 trillion; even the state’s expert agreed that the disparity was statistically significant. Based on these numbers, the court vacated the death sentences of three inmates and resentenced each to life without parole. Six months later, the state legislature repealed the Racial Justice Act.

Perhaps You’re Still wondering, despite all of the above, how Thomas Buffington ended up on the Fults jury.

The answer is simple. He lied:

Defense attorney: Do you have any racial prejudice resting on your mind?

Buffington: No, sir.

Defense attorney: Does it make any difference that in this case the defendant is black and the victim was white?

Buffington: No, sir.

Even this sort of cursory questioning wasn’t required by the Supreme Court until 1986, and then only in capital cases—and when the defense requests it. In order to function, the justice system has to presume that jurors will tell the truth under oath, just as it presumes lawyers are competent.

And what of the lawyers’ role? Since 1976, when mandatory death sentences were ruled unconstitutional, the decision of whether to seek execution has rested entirely with the local district attorney. In practice, this means a white man usually gets to decide who should face the death chamber. A 2009 study found that more than 85 percent of chief prosecutors in the United States were white, and the majority were male.

In the Fults case, that white man was William McBroom, district attorney of the Griffin Judicial Circuit. McBroom had already put two men on death row by the time he prosecuted Fults, and continued to aggressively seek and obtain death verdicts until 2004, when he lost his reelection by a hair. He wasn’t the type to fret over moral ambiguities: McBroom sought death sentences at every opportunity, thereby avoiding allegations of discrimination in the charging process.

His tough approach found an unlikely ally in Johnny Mostiler, the Spalding County public defender, who happened to be representing Kenneth Fults. “We’re finding ourselves facing crimes we think are Atlanta big-city crimes,” Mostiler proclaimed at one point. “We’re a law-abiding town. We want our criminals prosecuted.”

McBroom and Mostiler knew each other so well that the Fults transcript sometimes reads like old friends reminiscing: McBroom points out how Mostiler is going to respond, mentions an argument his rival made in an earlier case, and refers to him by first name before handing over the floor for closing arguments. “Mostiler was the toughest trial lawyer in Spalding County,” McBroom recalled some years after the Fults trial. “He would take cases where you didn’t think defendants had a chance, and you’d be fighting for your life.”

He had every reason to praise Mostiler. A death verdict is invariably followed by appeals in which the defense attorney’s work comes under close scrutiny. Prosecutors routinely hail their adversaries as giants in the field of capital defense to make it harder for any defendant to claim his lawyer was incompetent. And McBroom, who had obtained death verdicts against Mostiler in several prior cases, needed to defend some deplorable behavior: For all intents and purposes, Johnny Mostiler, like Thomas Buffington, was a racist.

Spalding County, 40 miles south of Atlanta, has but a single public defender to represent criminal defendants who can’t afford an attorney—and a great majority cannot. All through the 1990s, Mostiler was that defender, responsible for handling as many as 900 felonies a year. He also maintained a significant civil practice on the side and took on serious felony cases outside of Spalding County. But he was hardly your humble, nose to the grindstone type. According to a 2001 profile in The American Prospect, he stood out in a black cowboy hat; a silver beard with handlebar mustache; six gold, silver, and onyx rings; and three gold bracelets. He also drove a mustard-green 1972 Cadillac El Dorado convertible—with cattle horns as a hood ornament.

But Mostiler’s true legacy—he died of a heart attack a few years after the Fults trial—involved the case of his former client Curtis Osborne, who was tried in 1991, found guilty of murder, and finally scheduled for execution in 2008. As the clock wound down on Osborne’s appeals, a former US attorney general, a former Georgia chief justice, and former President Jimmy Carter (previously the governor of Georgia) all spoke out against the execution. They had heard the allegation by another one of Mostiler’s clients, a white man named Gerald Huey, that Mostiler had told him, speaking of Osborne, that “that little nigger deserves the chair.”

Some time later, a Georgia lawyer named Arleen Evans stepped forward with a sworn recollection about Mostiler’s personal conduct:

I recall one occasion when I was in the lawyer’s lounge at the Spalding County Courthouse. There were a number of other lawyers there including Mr. Mostiler. Mr. Mostiler began telling racist jokes filled with racial epithets like “nigger.” Some of the lawyers would laugh. Some would laugh nervously. Some would try to ignore it. And others would leave the room to get away from it. On another occasion, I remember walking into the lawyer’s lounge and Mr. Mostiler was again telling racist jokes. Ms. Nancy Bradford, who is now deceased, looked at me, noticed that it was making me uncomfortable, and told me “that’s just Johnny.”

Osborne’s lawyers soon dug up yet more evidence: a transcript from the trial of Derrick Middlebrooks, a black defendant who was so troubled by the racist talk that he asked the judge to dismiss Mostiler as his public defender: “He indicated to me that he wouldn’t—he couldn’t go up there among them niggers because them niggers would kill him,” Middlebrooks said. “Now personally I don’t know if he meant anything really by it. But I find it, you know, kind of hard to have an attorney to represent me when he uses those type of words. It doesn’t help my confidence in my attorney.”

“I honestly don’t remember,” Mostiler responded when the judge asked him about it. “I don’t use those terms out in public. And I probably—if I did use it I certainly am sorry. I didn’t mean to indicate that it was any—or any racial overtones. I think my—I think my record on race is…”

“Well documented in this court,” the judge interjected.

Mostiler was long dead by the time his racist language became an issue in the Osborne case, but several prosecutors, including McBroom and his successor, District Attorney Scott Ballard, spoke up in his behalf. Mostiler had presented a “very adequate defense” of Curtis Osborne, Ballard argued. He urged that the execution go forward.

Small counties tend to have incestuous legal communities. Public defenders and assistant district attorneys often swap sides and socialize together too; top assistants become bosses, and, most predictably, district attorneys end up on the bench. Such was the case with Johnnie Caldwell, Fults’ trial judge.

Caldwell had preceded McBroom as district attorney of the Griffin Judicial Circuit. As both a prosecutor and a judge, Caldwell was well aware of the racism allegations surrounding Mostiler. It was he, in fact, who had heard Middlebrooks’ claim and used the opportunity to assure the public defender, saying: “It’s unchallenged in this court with your actions concerning the races and certainly of standing up for the rights of all individuals regardless of their race or color or religious preference.” Turning to Middlebrooks, he added: “I find nothing in Mr. Mostiler’s conduct of this trial or in representing you that would cause me to disqualify him.”

By suggesting that the public defender of Spalding County—a man hired year after year by the county commissioners—was a racist, Middlebrooks had also, unwittingly, impugned the dignity of the prosecutor and the presiding judge. Caldwell was clearly put out:

Middlebrooks: My motion for a new attorney is denied?

Caldwell: Yes, sir.

Middlebrooks: Okay. Thank you.

Caldwell: And I know you’re sitting over there reading a book on ineffective assistance of counsel, you read it real well and write everything down, okay.

Middlebrooks: Yes, sir.

Caldwell: I’m directing you to. You write everything down and you write it well. You’ve been reading that book ever since you’ve been sitting over there.

Middlebrooks: Judge, that has—

Caldwell: Sir, don’t say anything else.

Middlebrooks: Yes, sir.

When race became an issue in the Osborne case, Caldwell didn’t step forward to disclose his interactions with Mostiler, nor did any of those other lawyers in the lounge, who had certainly heard the same racist jokes and comments Arleen Evans had. (Caldwell had his own problems: He resigned his judgeship in 2010 in light of allegations that he was soliciting female attorneys in open court. He was nonetheless elected, soon after, to the Georgia Legislature.)

Ultimately, neither local nor federal courts were moved by the consistency of the race testimony. In 2006, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals soundly rejected Osborne’s claim that Mostiler was ineffective due to racial animosity. (Osborne was executed two years later.) Citing McCleskey, the court said it was the racial animus of the decision makers—the prosecutors and the jurors, not the defense attorney—that mattered.

So what would the same court say eight years later, when lawyers for Kenneth Fults came before it with claims of racial animus involving a decision maker, the juror Thomas Buffington?

In September 2013, a three-judge panel of the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals convened in Miami to hear Fults’ claim. Half of their questions focused on legal hurdles, such as procedural default, cause and prejudice, impeachment of the verdict, and waiver. The other half dealt with the inexcusable nature of Buffington’s admission. The state wanted the court to reject Fults’ bias claim on a procedural technicality involving the rules of evidence, and Adalberto Jordan, the most outspoken of the judges, was struggling to understand why.

“When you have a claim of a juror potentially recommending a sentence of death because of flat-out racial bias,” Jordan asked, “why would the state of Georgia not want that claim heard on the merits?”

Assistant Attorney General Sabrina Graham insisted that Georgia law was clear on the issue. A verdict could not be reversed based on jury deliberations, no matter what any juror had to say about them afterward. In the process, she spent some awkward moments trying to persuade Jordan and Judge Stanley Marcus that what Buffington said wasn’t as damning as it sounded.

Graham: I think there could not be any prejudice.

Marcus: Tell me why there wouldn’t be prejudice, if in fact the juror was tainted with racism that affected his decision-making process?

Graham: I don’t think you would have enough information to show that. Certainly Mr. Buffington uses a racially derogatory term. I do not think that his particular affidavit shows that he sentenced Mr. Fults to death based upon his racism. People have many prejudices—

Jordan: “I knew I would vote for the death penalty because that’s what that nigger deserved.” You want something more specific than that?

Graham: I think you do want something more specific.

Jordan: Like?

Graham: That was eight years after—

Jordan: Like? Like what?

Graham: Like “I sentenced him to death based upon his race—

Marcus: Let’s suppose, just to take this to its logical conclusion, that there were 12 affidavits from all 12 jurors who voted for death, and each and every one of them said the same thing…Even if every juror says, “I voted to execute him because he was black,” you say, “That’s the law”?

Graham: That is the law.

That’s when Jordan, seemingly surprised by Graham’s answer, suggested that there was a “safety valve under Georgia law.” That is, if an evidentiary rule resulted in a violation of a defendant’s constitutional rights, it might justify an exception to that rule.

Graham conceded that such a ruling might be possible. “They have left that possibility open, but they have never actually done anything about it.” She then pointed out that there are many reasons to trust a juror’s answers during jury selection rather than statements the juror might make after a verdict of death is returned: “Fine, you want to say Mr. Buffington lied during voir dire. [But] you have the trial court, and you have defense counsel all watching these jurors.”

She was suggesting, in essence, that Johnny Mostiler, who had been accused of racism more than once, and Judge Caldwell, who’d belittled the claim of racism against Mostiler before being removed from the bench for harassing women in his own court, were suitable watchdogs to ensure an impartial jury. Was it possible she didn’t realize who they were?

The 11th Circuit was not entirely unfamiliar with juror bias. Back in 1986, a man named Daniel Neal Heller had been convicted of tax evasion in Florida. Evidence showed that Heller, a Jewish man, was the butt of anti-Semitic jokes in the jury room that consistently prompted “gales of laughter.” The trial judge, when confronted by vague claims of discriminatory comments by the jury, cursorily asked each juror if he or she was “affected by prejudice.” The 11th Circuit’s three-judge panel reversed Heller’s conviction, writing that the jurors’ religious prejudice was “shocking to the conscience,” and concluding: “The people cannot be expected to respect their judicial system if its judges do not, first, do so.”

The judges hearing the Fults case seemed to have forgotten the lessons of Heller. Despite their pointed questioning during oral arguments, the opinion they released 11 months later expressed neither shocked consciences nor fear of diminished respect for the system. If they were offended by Buffington’s admission, it was lost amid all of the procedural arcana.

The prevailing narrative about legal technicalities, thanks to Hollywood portrayals and posturing politicians, is that they open jailhouse doors—which is one reason crime sometimes seems to be on the rise when in fact it is plummeting. In reality, though, legal technicalities are far more often used to preclude people from having their postconviction claims heard. The Fults opinion, written by the outspoken Judge Jordan, is a virtual primer on how the law has evolved to block, rather than illuminate, allegations of injustice.

During oral arguments, Jordan seemed to be advocating a hearing to determine the circumstances of Buffington’s admission. In his opinion, however, he condemned the defense for failing to provide sufficient detail about how or when Buffington’s prejudice was discovered. While he had earlier questioned why Georgia didn’t want a claim of “flat-out racial bias” heard on its merits, his opinion articulated every reason the claim had not been properly presented, and now could not be considered.

Finally, “in an abundance of caution,” he addressed the argument he seemed to be championing 11 months earlier: that the failure to consider Fults’ racial-prejudice claim would be a miscarriage of justice. Once again, Jordan felt compelled to explain that this claim had not been properly presented. In any case, he concluded that Fults had not shown that his sentence was a miscarriage of justice. For while it’s true that in Georgia a single juror can stop a death sentence from being imposed—the jury has to be unanimous—the bar is much higher for a death row inmate seeking to overturn his sentence. Fults’ legal burden was to demonstrate that no reasonable juror would have voted to give him the death penalty. And this, in the court’s view, he had not done.

So how, exactly, does a “reasonable juror” think?

It’s difficult to think of any decisions more subjective than who should live or die. Every death penalty state has a statute with language intended to objectify the determination, but when all is said and done, it’s highly personal: Will the person be a danger in the future? Do the circumstances of the crime trump the defendant’s background? Do the reasons for a life sentence outweigh those for a death sentence?

And how might this hypothetical reasonable juror regard Kenneth Fults? The man pleaded guilty to a horrible crime. He committed two burglaries and stole some handguns, all with the intention of killing a man involved with his former girlfriend. Instead, he ended up shooting a neighbor, Cathy Bounds, five times in the back of the head.

But, as the Supreme Court has pointed out, there are “potentially infinite” reasons a juror might want to sentence someone who has committed a heinous crime to something less than death. Kenneth Fults’ history was packed with them.

“I just lost sight of raising my kids,” his mother, Juanita Wyatt, told a state court judge, explaining the result of her crack and alcohol addictions. She was court-martialed from the military for writing bad checks to buy drugs, moved her children from house to house and state to state, abused them with switches and belts and electrical cords—using the plug end when the cord itself ceased to have the necessary impact. Whatever boyfriend happened to be with her at the time often joined in. As for Kenneth’s father, the man was no more than a name to him.

Kenneth’s mother didn’t just lose sight of raising her children—she lost sight of them entirely. His younger sister remembered how their mom had abandoned the kids after moving the family to Houston:

We stayed there alone without any adults watching over us so long that the power company had turned off all the utilities. We didn’t have heat or lights; I don’t remember if we had water. I don’t remember how long we were alone…I know it was at least a couple of months. I was really scared. Kenny and Michael tried to make it like it was fun and we were just camping out or something. I know they started stealing for us to have something to eat, because we did not have any money. I also remember that Michael had them dig a hole in the ground in the backyard to bury some of our food to try and keep it cold when our electricity was turned off.

Legally speaking, the most compelling reason not to sentence Fults to death is that he may be intellectually disabled. Three separate IQ tests over a 16-year period, one of them seven years prior to the murder, all fall within the range for mental retardation. By seventh grade, Fults was testing near the bottom in basic skills. In eighth, he was placed in a “special class…for slow learners.” In that class, a former teacher recalled, Kenny was the “poorest performing student.” There also was abundant testimony that he was incapable of keeping his money straight or filling out job applications. And as a child, he related to far younger children.

Even Judge Jordan, in rejecting Fults’ claim of intellectual disability in the 11th Circuit, acknowledged that his lawyers’ argument was “not without some force.” But again, procedural rules came into play: Since the state court had rejected the claim, its decision was presumed correct, and only “clear and convincing” evidence could overturn it. The IQ tests, the academic struggles, the affidavits of family members and teachers and friends detailing his “slowness,” none of that was enough.

As for what a reasonable juror might have done with all of this information, we’ll never know. Johnny Mostiler didn’t present any of it to the jury.

Kenneth Fults has one last stop before his appeals run out. The likelihood that the US Supreme Court will review any matter is remote, but there could be a tiny sliver of hope for him in a civil case, Warger v. Shauers, that the court decided last December. On its face, the unanimous ruling seems as though it would be to Fults’ detriment: Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s majority opinion echoes what lawyer Sabrina Graham had argued on Georgia’s behalf in the Fults case: that what a juror says later cannot be used to attack the verdict.

You have to read the fine print, footnote No. 3 to be exact, to find the passage that could be Fults’ saving grace: “There may be cases of juror bias so extreme that, almost by definition, the jury trial right has been abridged. If and when such a case arises, the Court can consider whether the usual safeguards are or are not sufficient to protect the integrity of the process.”

As much as Georgia wants to make the case about a rule of evidence, it is not really about that at all. It is, instead, about Footnote No. 3, and that most extreme form of juror bias: sentencing a man to death based on racial hostility. And maybe it’s also about how far we are willing to go, and how many procedural barriers we are willing to erect, to avoid dealing with the ramifications of such behavior.

How do we know when we’ve crossed the line, when our system of justice simply can’t tolerate a result that its technical rules encourage? Here’s Buffington’s full statement: “That nigger got just what should have happened. Once he pled guilty, I knew I would vote for the death penalty because that’s what that nigger deserved.”

Racism doesn’t get much clearer than that. Now it’ll be up to the Supreme Court to decide whether the rules of evidence might, just this once, take a backseat to the principle that no man should be judged by the color of his skin.