Illustration by Mark Ulriksen

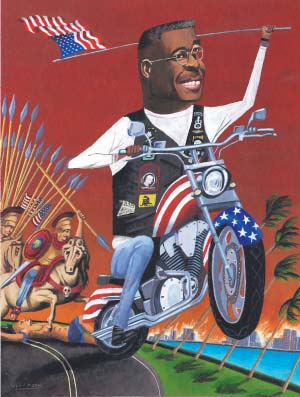

Illustration by Mark Ulriksen

The bike is immaculately polished and gleaming in the late afternoon South Florida sun. A bald eagle in full squawk graces the gas tank, white stars checker the front fender, and a tattered red-and-white-stripe motif designed to evoke Old Glory covers the rest of the body. Any hint of grime or dust is purely aesthetic; 22 years in the military teach a man to clean up after his mess. The helmet sits right-side-up on the saddle and is adorned with two rows of jagged teeth and a bright red tongue, like the nose of an old Spitfire; two US Army logos; six bullet-hole decals; and, down at the bottom, the signature of its owner, who has just roared up: retired Lt. Colonel Allen B. West.

It’s mid-April and momentarily West, the Republican congressman from Florida’s 22nd District—an imaginatively carved Tetris piece stretching from West Palm Beach to the outskirts of Fort Lauderdale—will take the stage at the Palm Beach County Tax Day Tea Party in Wellington. He’ll call the tax on tanning salons enshrined in the Affordable Care Act “racist,” the president “an abject failure,” and, directing his assembled battalion’s attention to a small group of placard-bearing liberal protesters, ruminate on his sanity: “They say Allen West is the craziest person that ever set foot on the House floor! Let me tell you who’s the craziest person to truly ever set foot on the House floor. That’s President Barack Hussein Obama.”

For now, though, everyone wants a piece of West and his Honda VTX 1800R retro cruiser. West poses for photos at a short remove, offering a firm grip and flashing an undeniably charming, gap-toothed grin. “A true patriot,” gushes a woman in a red tank top, to no one in particular. “A true patriot!”

His vest is black leather like his boots, and it’s covered in patches—”Rolling Thunder: First Amendment Demonstration Run, Washington, DC, Inc.” across the back, “Christian” on the front. Tucked in the right breast pocket is a copy of the Constitution.

“He’s our local rock star!” says a voice in the crowd. She’s holding a copy of a book about radical Islam for which West wrote the foreword. The cover features a flaming Islamic crescent and star behind the Statue of Liberty. She grows gravely serious. “Just protect him, God. Protect him, Lord.”

Sixty years ago Wellington was pure Everglades, part of an undulating expanse of saw grass and cypress that stretched for hundreds of miles down into Florida Bay. In the years since, the land has been drained, filled in, bought and sold and repossessed. In its place, a fever swamp of an entirely different sort has emerged. Allen West, tea party rock star, is its champion.

Since thumping Democratic Rep. Ron Klein at the polls in 2010, West has taken dead aim at the lily-livered sissies he believes are running America into the ground—and the Islamic extremists he’s convinced are poised to seize control. He has suggested that Democratic leaders—whom he calls “chicken men“—”get the hell out of the United States of America”; considers drivers with Obama bumper stickers “a threat to the gene pool“; and says black Democrats are trying to keep his fellow African Americans “on the plantation”—and he’s the “modern-day Harriet Tubman” helping them to escape.

Of the 94 freshman congressmen who came to Washington in January 2011, none captured the id of the tea party movement—and the ire of the left—as perfectly as West, an Army veteran who retired in 2004 after firing his gun, Jack Bauer-style, past the head of an uncooperative Iraqi detainee. Reborn as a conservative icon, he is the torch carrier for a political culture and a region where, more than anyplace else in the country, radical Islam is the existential threat lurking around every corner.

Activists and aspiring politicians bask in his glow. Sarah Palin and Ted Nugent want him to be vice president; Glenn Beck wants him to be president. Democrats, who have made him one of their top targets in 2012, think the best way to shut him up is to just let him keep talking. Swept into power at the crest of the tea party, his reelection battle this fall will be a measure of just how far those waters have receded.

Let’s get this out of the way: Allen West does not regret a single Red-baiting, Obama-hating thing that he’s said during his career in political office. “I’m not like the president,” he snipes. We’re in the lobby of the Palm Beach Synagogue, a pastel-colored building squarely in the middle of an upscale, palm-tree-lined community, where a man’s affluence is measured by the height of his hedges.

West, wearing a green camouflage yarmulke and the same leather Rolling Thunder vest, has just held forth in the sanctuary for 45 minutes on debt and taxation and radical Islam, sprinkled, here and there, with token Westisms like “Katie, bar the door!” I was told by his staff we’d have a few minutes to chat after the event, but now he’ll have to keep it short because he needs to take a leak.

“My parents raised me very conservatively, and I think that’s what you have to understand,” he says when I ask about his upbringing. “That’s what you have to understand”—it’s a phrase West uses a lot, usually followed by a discourse on the Koran (he says every American should read it) or the Progressive Era.

He grew up in a middle-class household in Atlanta, the son of a World War II veteran. His parents, Herman and Elizabeth, were both Democrats, but with a conservative bent. They taught him to read the stock index in the Journal-Constitution and to scorn the thought of a handout. “The Democrat party was once upon a time a very conservative group,” he says. West is uncompromising, right down to his grammar. Every sentence is a proxy war in the larger struggle between patriots and the “people in this world that just have to have their butts kicked,” and as a consequence he never—never—gives the Democratic Party the dignity of an adjective.

“As Ronald Reagan said, ‘I didn’t leave the Democrat party—the Democrat party left me.’ The Democrat party my parents were members of back when I was growing up is not the same one today. They raised me to be exactly what I am today. It’s about principles of governance.”

Fiercely apolitical during his military years, West didn’t even register to vote until after he left the Army. He served in ROTC through high school and stuck with the program in Knoxville, where he received an officer’s commission and graduated from the University of Tennessee. By all accounts, it was the Army that shaped his life.

By the time he was assigned to a base 20 miles north of Baghdad in 2003, Lt. Colonel West had command of 650 troops; he was tasked with making inroads with the locals. “There I’d be, an inner-city kid from Atlanta sitting on the floor like Lawrence of Arabia, with 30 Arab sheiks,” he later told the New York Times. That August, West received intelligence about a potential plot on his life. A week later, the convoy he was scheduled to be traveling in was ambushed. A few days after that, West arrested an Iraqi policeman, Yehiya Kadoori Hamoodi, who he believed had inside knowledge of the plot.

In testimony at an Army hearing that November, West would state that he had watched four of his subordinates beat the detainee, delivering blows to Hamoodi’s chest and legs. Finally, he stepped in. West took the detainee outside, pulled out his 9 mm, instructed Hamoodi to place his head in a barrel full of sand, and fired into the barrel. The detainee screamed, called for Allah, and started to talk. But the house Hamoodi suggested searching yielded no leads; he was released 45 days later and was never charged with a crime.

The high-profile case effectively ended West’s military career. He avoided a court-martial but was ordered to pay a $5,000 fine and was banished to the rear in a noncombat role. West didn’t regret a thing: “If it’s about the lives of my soldiers at stake, I’d go through hell with a gasoline can.“

West garnered thousands of letters of support—including from members of Congress. FrontPage Magazine, an online publication founded by David Horowitz to raise awareness of radical Islam, named him its 2003 man of the year for “valuing his own troops’ lives over the mental well being and self-esteem of an Iraqi terrorist.” A former instructor at West Point was so moved by the case he published a book about it. “If there is a hero walking the planet today, it is Allen West,” he wrote.

West returned to Fort Hood, Texas, and then moved with his wife, Angela, a financial planner, and two daughters to Plantation, a suburb of Fort Lauderdale on the edge of the Everglades. His future was uncertain; he got a job, over the protests of at least one faculty member, teaching history and coaching track at a nearby high school in Deerfield Beach. In his free time, West, a certified master diver, planned on being a scuba bum.

But that spring he got the military itch again. He announced he was leaving for Afghanistan, where he’d taken a job with an independent contractor to train the Afghan army and develop its infrastructure. It was there that he began writing for Pamela Geller’s blog, Atlas Shrugs, which has been classified as hate speech by the Southern Poverty Law Center for its depiction of Islam. Starting in 2007, he penned a monthly dispatch for the site, “Column From Kandahar.” Geller referred to him warmly as “one of my most valued warrior correspondents.”

In those columns you can see the future congressman finding his voice. He cites John Stuart Mill and William Tecumseh Sherman (“War is hell”) and casts his work overseas in historical terms: America is following in the footsteps of Charles Martel at Tours, and before that the legendary 300 Spartan hoplites at Thermopylae, in defending Western civilization against threats from the East.

“There are those who will hate your own country, America, regardless of the self-evident truths,” he wrote in his debut column. “To you I say that life just does not get any better than the ‘Land of the all night IHOP’…and if you truly hate America so much, you are also free to find another home. There is surely an illegal immigrant who will be happy in yours.” In 2006, Ron Klein, a promising young moderate Democrat, had unseated 13-term GOP incumbent E. Clay Shaw and turned West’s backyard into a swing district. With Geller’s full-throated encouragement and a growing base of support among the conservative grassroots, West began plotting his first congressional campaign from Central Asia.

Back at the synagogue, I ask West when he first recognized radical Islam as an existential threat. “Uh, let me see, the first time somebody shot at me?” comes the irritated reply. I ask him to elaborate, but his bladder is full and my time is up. “Oh, come on,” he says, and walks off.

Fort Lauderdale, December 30, 2008—for South Florida’s anti-Muslim activists, this was their Lexington and Concord. It came in the middle of the Israeli conflict in Gaza, and a group of Muslim, pro-Palestinian demonstrators held a protest across the street from a smaller band of Israel supporters. “It was the day that the jihad was uncovered in Fort Lauderdale, Florida,” says Tom Trento, founder of the United West, a group dedicated to exposing radical Islam in the United States and Europe. And it was also the day that West, who had just lost his first congressional race against Klein, solidified himself as a hero of the cause. “I don’t know if you’ve seen the video,” Trento says.

Trento is referring to the shaky footage he shot. In it, you can hear him muttering periodically that things aren’t looking good. After an imam leads the demonstrators in their evening prayers, some of the younger Muslim men cross the street to confront the counterprotesters. Trento was bracing for violence. “And then, out of the shadows, there comes Allen West,” he says. West joined forces with a handful of police officers and, like a modern-day Charles Martel, pushed back the Muslim demonstrators.

Trento posted the video and it went viral, eventually garnering a half-million hits and counting. The event resonated so deeply with South Florida’s counterjihadists that the next year the participants gathered to commemorate it on the same street corner, like old warriors returning to Normandy. West was a featured speaker. Dressed in a black bomber jacket, collar up, and flanked by Israeli and Marine Corps flags, he let loose. “They came and they charged us,” he said. “And for those of you that were there, we withstood. When they thought that we would turn and run away, we said, ‘It ain’t happenin’, that dog don’t hunt, take your pro-Hamas butt and get the hell out of my country!'”

I meet Trento, at his request, at the Atlantic Avenue pavilion in Delray Beach, a place with unique significance to South Florida’s anti-Shariah movement. Down the street is the pharmacy frequented by 9/11 hijacker Mohamed Atta in the weeks leading up to the attack. Across the street is the Delray Beach Marriott, where, in 2009, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) succeeded in blocking a scheduled appearance by Geert Wilders on the grounds that the Dutch politician’s past statements on Islam constituted hate speech.

Trento hails from Jersey, a pedigree he reinforces by calling me “Timmy” and punctuating his answers with “capisce?” He insisted on videotaping the interview—”My viewers will get a kick out of it!”—and takes evident delight in thrusting a mic in my face, all the while puffing on a big fat cigar.

In 2007, the longtime conservative activist joined with a GOP state representative named Adam Hasner to form the Florida Security Council, the forerunner to the United West. Trento’s work now revolves around “gathering intelligence” on the Muslim community, visiting mosques and public events with cameras rolling to find incriminating evidence. (In the Fort Lauderdale video, one protester is heard chanting at the pro-Israel activists, “Go back to the oven!”) “Some people are overt; some people are covert,” he says of his operatives, but “we get the information we need legally, no guns or bullets.”

The lingering aftershocks of 9/11—the city of Wellington paid almost half a million dollars to install a piece of World Trade Center steel in a parking lot—have combined with changing demographics to produce a volatile stew of Islamophobia in South Florida. Long home to a large population of Jews and evangelical Christians with an acute sensitivity to all things Israel, the Sunshine State has received an influx of Muslim immigrants over the past few decades. Activists view the area’s smattering of terrorism-related indictments during that time as a harbinger of what’s to come. As a result, South Florida has become a launching pad for a half-dozen groups and an array of self-styled experts fixated on beating back the menace of radical Islam and Shariah law in Florida. And West has close ties to most of them.

There’s Walid Phares, a leading scholar of “stealth jihad” and a onetime political adviser to a Lebanese Christian paramilitary group, who taught Trento at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton (and currently advises Mitt Romney on foreign policy). Joe Kaufman, a friend of West’s who runs the anti-Islam group Americans Against Hate, lives in Broward County; Joyce Kaufman (no relation), a local conservative radio host, campaigned against the grocery chain Publix for including the Islamic New Year in its wall calendar and was—briefly—tapped by West to be his chief of staff. Citizens for National Security, based out of Boca, works to raise awareness of Islamic propaganda in school textbooks, among other places. (In 2011, West invited the group to Capitol Hill, where its leaders announced they had a list of 6,000 members of the Muslim Brotherhood currently living in the United States but could not release it due to security concerns.) Reverend O’Neal Dozier, a black pastor who’s a GOP fixture, preaches out of a Pompano Beach church where West has spoken from the pulpit; Dozier’s claim to fame, at least as far as Islam is concerned, came in 2006, when he protested the construction of an Islamic center by handing out comic strips attacking the Muslim faith. The list goes on.

A chief target of the groups is CAIR, the nation’s largest Muslim civil rights organization and, according to the counterjihadists in South Florida, the Muslim Brotherhood’s smiling public face in the United States. No one has borne the brunt of the Sunshine State Holy War more than Nezar Hamze, a former car dealership employee who became the organization’s regional director in 2010.

Hamze, who’s half-Lebanese and a registered Republican, is built like a lineman and sports a flattop. His political leanings were solidified when as an elementary-school student he wrote a letter to President Reagan and got a handwritten response. A regular at county Republican meetings, his attempt to formally join the Broward Republican Executive Committee was rebuffed in 2011 when activists accused him of being a terrorist.

Hamze has had a series of run-ins with West. At a town hall meeting in Pompano Beach last winter, Hamze, Koran in hand, challenged West on his assertion that Islam was a “totalitarian” belief system.

West responded by ticking off a detailed timeline of conflict between Muslims and the Western world. “Something happened when Mohammed enacted the Hijra and he left Mecca and he went out to Medina,” West said. “It became violence.” Hamze was shouted down with cries of “Taqiyya alert!”—a reference to the Islamic principle that activists claim instructs jihadists to lie about their true intentions.

“I’ve been on the battlefields, my friend,” West told him. “Don’t try to blow sunshine up my butt.”

“He uses his high-school-insult-type strategy; it’s not unique to Muslims—he does that to everybody,” Hamze says. “Anyone who doesn’t agree with him, he turns on the high-school-boy-insult mode. And everyone loves it.”

West’s a fan of the World War II miniseries Band of Brothers and the real-life unit it followed, the Army’s 101st Airborne Division. So when Hamze later wrote to his congressman asking him to denounce extremists, including Geller, following the July 2011 Norway terrorist attacks (she had figured prominently in gunman Anders Breivik’s manifesto), West didn’t have to reach far for a response. He simply cribbed from the 101st’s defiant one-word letter to the Nazis, who had requested the Americans surrender their position at Bastogne:

“NUTS!“

WEST DIDN’T JUST ride the tea party’s wave in 2010—in many respects, he is the movement’s political avatar. Three years ago, West’s second congressional campaign was catapulted forward at a tea party rally where he captured activists’ hearts with one of his trademark fiery (critics would say unhinged) speeches aligning their cause with that of the American Revolution. “As a great man said in December 1776: ‘These are the times that try men’s souls. When the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will in this crisis shrink from his duties.’ If you’re here to shrink away from the duties, there’s a door—get out,” he told activists during his last campaign. “But if you’re here to stand up, to get your musket, to fix your bayonet, and to charge into the ranks, you are my brother and sister in this fight.”

West acknowledges the centrality of race to his political appeal. “If I were still that inner-city young black man in Atlanta, maybe…on drugs, with a bunch of children from different mothers, not out working, I would be their poster child,” he says of the left. As it is, he’s their nemesis—a black man who’s left what he calls the “21st-century plantation.” Although he’s clashed with his base on occasion—condemning, for instance, Newt Gingrich’s proposal to reinstate poll tests—to tea partiers, he’s a one-man counterpoint to the notion that racial animus has any place in their movement. The irony is that West’s acceptance comes largely from his willingness to castigate another American minority group: Muslims.

West implores his followers to read Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals to understand what they’re up against—and learn how to tackle it—and has adopted Glenn Beck’s conspiratorial whisperings about progressivism. A few days before we met at the synagogue, he’d implicated the entire Congressional Progressive Caucus as card-carrying communists, and he’s not backing down. He never backs down.

“At first glance, I go, ‘That sounds a little out there,'” says Eleanor Duffy of Jupiter, Florida. “I hate all that melodramatic stuff. But there are a lot of communists. Because I respect him, I’m willing to look at it. If Allen West said it, I’m going to look into it.”

Only once has West truly been challenged on his tea party bona fides, and then only briefly. When House Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) wanted to inspire his fellow Republicans to swallow their pride and vote to raise the debt ceiling last summer, he brought them together in the Capitol and showed them a short clip from The Town, the Ben Affleck flick in which a band of Boston gangsters dress up like nuns and rob a bank. In the scene in question, Affleck’s character makes an appeal to a friend: “I need your help. I can’t tell you what it is. You can never ask me about it later. And we’re gonna hurt some people.” His friend pauses for a beat, and responds: “Whose car we gonna take?”

West rose, and, amid the 242-man House Republican caucus, volunteered his services: “I’m ready to drive the car.”

Tea partiers, including Trento, called the debt ceiling vote a betrayal, but in the end the backlash was minimal. Allen West can’t betray the tea party; Allen West is the tea party.

PATRICK ERIN MURPHY, the 29-year-old vice president of an environmental cleanup firm, would like nothing more than to make West a congressional has-been.

He “really just spews hatred,” the political novice who’s running against West says when we meet at his Palm Beach Gardens campaign headquarters in April. “He has no problem lying. He has no problem distorting the truth. There’s no place for that in our country.”

“And,” he adds, “the latest one about the progressive caucus being communists—you can’t say something like that and not expect consequences.” Palm Beach Democrats have adopted West’s jabs as a badge of honor, literally; volunteers at the opening of Murphy’s campaign office wrote “communist” on their name tags and addressed each other as “comrade.” “I never saw so many communists in the same room,” Murphy joked to supporters.

It will be a close race, though money won’t be an issue for West. One benefit of regularly accusing the opposition of high treason is that it opens up wallets across the country. He had $3.3 million on hand after the first quarter, an enormous sum for a House race. Murphy, meanwhile, has so far banked nearly $2 million—more than almost any other Democratic House challenger in the country.

In late January, following Florida’s redistricting, West opted to shift from the redrawn 22nd District to the more politically favorable 18th. Murphy followed him—a bad move, according to West, who compares the race to the Battle of Cannae during the Second Punic War. “If he goes back and studies Hannibal, you may not want to follow a very savvy person that just avoided an ambush, because obviously they got something that’s waiting for you,” West told Roll Call.

Of note: Hannibal—and his elephants—won the battle but lost the war.

IN WELLINGTON, West has a six-man security detail, volunteers in New Balance kicks and floppy hats with cloth flaps in the back in the style of the French Foreign Legion. They don’t look especially capable of stopping anyone from doing anything, but they do have one thing going for them: They are absolutely not members of the Outlaw motorcycle gang.

The Outlaws are what are known in biking circles as “1 percenters,” so named not because of their affluence but because unlike the 99 percent of bikers who are peaceful and law-abiding, they’re out to raise hell. An all-white motorcycle club—one of its insignias used to feature a swastika—the Outlaws are infamous for their violent crimes, racism, misogyny, and (paradoxically) undying support for Allen West.

During the 2010 campaign, it came out that West had penned a monthly column, “Washingtoons,” for a Florida-based biker magazine called Wheels on the Road, which featured Outlaw ads and bulletins along with occasionally racist and misogynist content. West had appeared with the Outlaws at campaign events and even used them for security during press conferences. His opponent tried to make an issue of it, but in vain—in part, says the editor of Wheels on the Road, because West couldn’t possibly have been an actual Outlaw: “Every biker knows that there are no blacks allowed in the Outlaws.”

The editor, a thickly bearded man who goes simply by “Miami Mike,” calls West a friend and says the appeal for bikers goes beyond the congressman’s affinity for motorcycles—it’s an attitude thing. “We call a Fuckin’ Muslim Terrorist a Fuckin’ Muslim Terrorist,” Miami Mike tells me in an email, “and FUCK that politically correct shit which is bringing down this country and which will get a lot of people killed by some deranged Fuckin’ Muslim Terrorist with a bomb strapped to him (or herself) in Midtown Anytown USA.”

In West, they’ve found a politician who actually gets it.

WEST FINISHES HIS speech in Wellington, thanks the crowd, tips his Navy SEALs baseball hat once, and exits through the back of the hatch-shell amphitheater. The crowd swarms the exit, hoping to catch an autograph or just a final glimpse of Congress’ biggest badass.

West fires up his bike and wheels away. We watch him glide off, a solitary figure melting into the distance. The middle-aged woman beside me can’t contain herself. “I can’t believe he just goes on the road by himself, and he’s not concerned that someone’s gonna follow him and shoot him,” she says.

Does she really think someone would go after Allen West?

“You never know,” she says, not skipping a beat. “People are crazy today.”