In 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared that measles had been eliminated in the United States. Now it’s making a comeback, in large part due to parents who refuse to vaccinate their children.

This year’s outbreak—more than 100 cases reported across 14 states—follows a dramatic rise in measles cases in 2014: 644 cases across 27 states. In light of the the potentially deadly disease’s return, public health officials are expressing concern about rising vaccine exemption rates. Citing the risks of not vaccinating, Anne Schuchat, an assistant surgeon general and the director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, stressed that measles could get “a foothold in the United States and [become] endemic again.”

Every state requires children to get the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine before they enter kindergarten. (The vaccine is usually administered in two doses after a child’s first birthday.) All states offer medical exemptions for kids with allergies, cancer, or compromised immune systems. Most offer religious exemptions as well. And now a growing number of states—20 as of this year—permit personal belief exemptions (PBEs) that allow parents to not to vaccinate for reasons of philosophy or conscience.

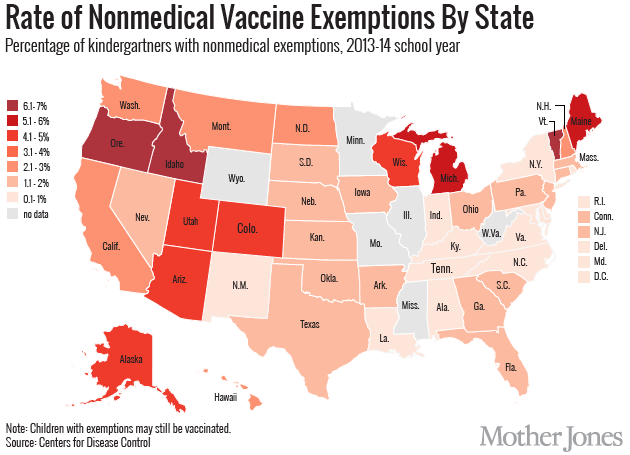

Nonmedical vaccine exemptions—the rules that allow parents to opt their kids out of required vaccines based on beliefs—are on the rise. Over the past four school years, there’s been a 37 percent increase in exemptions filed. Between the the 2010-11 and 2011-12 school years, the rate of exemptions for incoming kindergartners jumped 30 percent. The CDC reports that 85 percent of people who go unvaccinated do so for personal or religious beliefs.

According to a 2012 study led by Saad Omer, a professor of global health and epidemiology at Emory University, allowing PBEs leads to fewer kids getting vaccinated. Opt-out rates in states with PBEs are more than double those in states with religious exemptions alone. These vaccination gaps result in higher rates of diseases like measles and whooping cough, especially in states where PBEs are easily obtained.

“We do know that states that have philosophical exemptions tend to have not only high rates of exemption but also high rates of disease,” Omer says. But some states grant exemptions more readily than others. In states such as Colorado, a parent’s signature is all that is required. But in states like Arkansas, parents must first establish why they are seeking an exemption or receive counseling from a health care provider. “We have found that the more difficult the requirements are, the lower the rate of exemption and the lower the rate of disease,” Omer says.

Looking at data from 1991 to 2005, Omer’s team found that states with easy exemption procedures had whooping cough rates up to 90 percent higher than states that made it more difficult to get exemptions.

Last year, nationwide vaccination coverage was at about 95 percent, and the median national rate of children with PBEs was 1.7 percent. That might not seem so bad. Yet because unvaccinated kids are often clustered together, one transmission of a highly contagious disease like measles can put many people at risk and set off a series of outbreaks like those happening now.

These “clusters of vaccine refusal” put two groups at risk, Omer explains. First are people who are not vaccinated, which may include infants and children with compromised immune systems. The other is people who have gotten their shots but did not get immunity—something that affects about 1 in 10 vaccine recipients, even with the most effective vaccines. “Even when it is a good vaccine and someone has done the right thing and gotten their kid vaccinated, there is still a chance that they will be unprotected,” Omer says. “So, their risk not only depends on their own vaccination status—but also what is happening around them.”

As Schuchat noted earlier this week, “The national estimates hide what’s going on state to state. The state estimates hide what’s going on community to community. And within communities there may be pockets. It’s one thing if you have a year where a number of people are not vaccinating, but year after year in terms of the kids that are exempting, you do start to accumulate.”