<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/coast_guard/3447860739/sizes/m/in/photostream/" target="_blank">U.S. Coast Guard</a>/Flickr

The 1.8 million gallons of dispersant that BP and federal responders spread on the massive Gulf oil spill in 2010 are already coming back to haunt them. FuelFix.com, a Houston Chronicle spinoff devoted to covering energy, reports today that the company that manufactures Corexit, the chemical sprayed on the surface of the Gulf and at the wellhead to disperse the oil in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, is trying to get out of a proposed settlement with plaintiffs who say they have health problems resulting from the spill and cleanup.

Corexit manufacturer Nalco wants the US district judge handling the case in New Orleans to exempt it from any liability in the settlement of a class action lawsuit brought against BP and other companies involved in the disaster on behalf of more than 10,000 plaintiffs. In March, the plaintiffs and BP reached a settlement agreement that is expected to cost $7.8 billion and would cover both economic loss and medical claims, and would also establish a program to monitor the health of affected individuals. The judge is now deciding whether to approve the agreement, but Nalco says that not only should it not be included the companies that are asked to pay up in this case, but it should be excluded from any future cases:

The spill responders contend that the federal Clean Water Act provides them immunity from liability for actions taken at the government’s direction.

“Nalco provided Corexit at the express request of the federal on-site coordinators,” Nalco attorneys wrote in the dismissal motion filed in May. “Nalco supplied a product that was and had been listed on the federal government’s list of approved dispersants for decades and that the government repeatedly approved for use during the response.”

This is a compelling argument, because it is true: Corexit was listed as an approved dispersant, and it was what BP decided to use on the Gulf. The problem, though, is something we’ve covered here before: The federal government doesn’t consider the human or environmental effects of the chemicals when approving them for the list. Companies like Nalco don’t even have to disclose what kinds of chemicals are in their product in order to get them approved, thanks to the extremely outdated and industry-friendly chemical regulation laws in this country. Current chemical regulation laws actually makes it really difficult for the Environmental Protection Agency to do more than give these chemicals a rubber stamp.

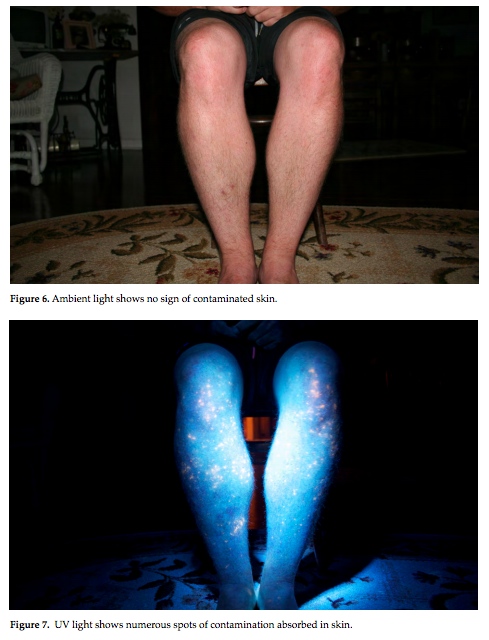

Meanwhile, chemicals used in the dispersant can cause liver and kidney damage, as well as other health problems. Studies since the spill have found that the dispersants are sticking around longer than people expected and can be absorbed through the skin. In the weeks and months after the spill, many cleanup workers and nearby residents complained of ill health effects like nausea and rashes they believed were caused by the chemicals. So is Nalco liable for supplying the chemicals, or BP for buying them, or the federal government, which was supposed to be overseeing the clean up work?

If Nalco is granted an exclusion in the lawsuit, it would leave the plaintiffs who believe they are sick because of exposure to the chemicals in a tough spot: they can sign onto the settlement now, or try again to sue Nalco later. Neither option is great, according to the lawyers representing the plaintiffs:

“We are recommending the medical settlement program for most of our clients, even though it leaves Nalco off the hook,” [Beaumont-based lawyer Brent] Coon said. “The reality is, most people exposed to these kinds of toxins don’t develop a disease for many years. For most plaintiffs that were exposed, it is premature to sue, and the medical monitoring program at least develops a mechanism to measure how they were impacted.”

But Louisiana-based lawyer Daniel Becnel says he is encouraging the 3,500 cleanup workers he represents to fight their cases in court.

“I have hundreds of people that are horribly sick,” Becnel said.