“Every relationship is a transaction” for 32-year-old Donald Trump, wrote Wayne Barrett in 1979, when he was the first investigative reporter to take Trump seriously as a threat to anyone within breathing distance. “Donald Trump is a user of other users. The politician and his moneychanger feed on each other. The moneychanger trades private dollars for access to public ones.”

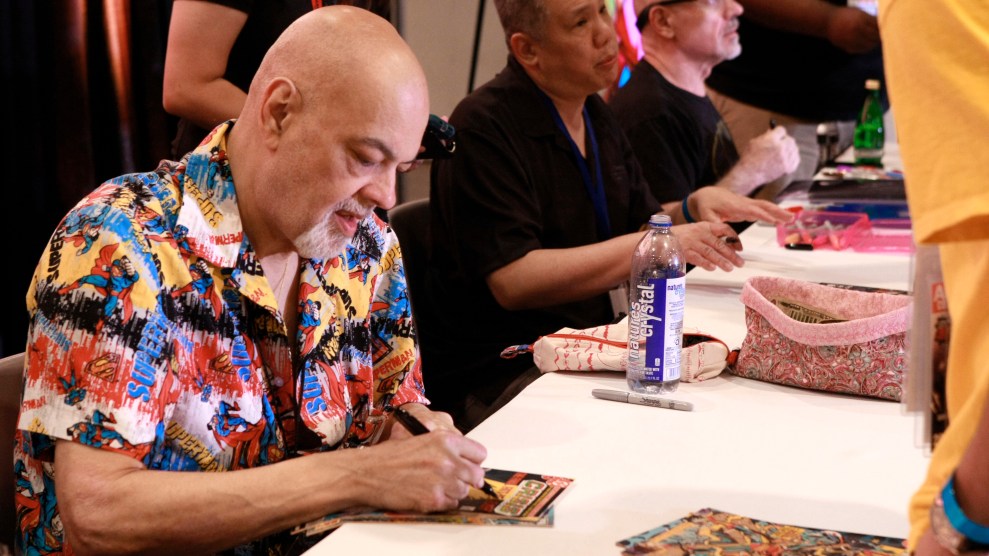

It was scandalous stuff in the ’70s, but Barrett stayed on the trail. He died one day before Trump’s inauguration, but the legendary Village Voice reporter is still at it: Last week saw the publication of his new collection, Without Compromise: The Brave Journalism That First Exposed Donald Trump, Rudy Giuliani, and the American Epidemic of Corruption.

By now there’s nothing surprising about Trump past or present, but there is a measure of hope in revisiting the early days and many ways that bad news about him was delivered, especially in the strong writing of the first to do it. Barrett was unflinching. Trump threatened to sue him for his investigations and apparently tried to bribe him in exchange for softening or shelving the stories, the Voice reported: Trump “subtly hint[ed] that he could get Barrett a nice apartment in midtown and move him and his wife out of the Brownsville home where they lived.”

It’s all prescient and preserved: the abdication of responsibility, the self-dealing, the downplaying of disaster: “Trump has a pathological need to introduce an evil twist into every deal.”

Trump is the easiest target today. He wasn’t then. If you haven’t read Barrett, the archives await—Mother Jones tributes here and here, the Voice here. It’s worth a spin, less for the gritty details than for the visceral experience of clicking on the earliest evidence that Trump has always been, down to his toes, a virus, and someone was fearless in saying it.

Barrett was tall. His temper was short. I worked a cubicle away from him, and there’s a story about a fact-checker who got a newsroom shouting after booking Barrett a first-class train ticket to speak to students. Barrett flipped. He recalled the time an airline agent had awarded him a first-class ticket as compensation for a mistake. Barrett lit into the agent: “I will not fly first class!…I don’t believe in first- and second-class people.” It’s an easy thing to say, and easier to applaud. For Barrett it wasn’t rhetoric. He reported that way and lived that way.